The need for diversity in the chemical industry

Abstract

The signs are clear, the focus on Diversity & Inclusion (D&I) in business is by no stretch of the imagination just a fad. It will therefore also remain an important issue for chemical industry companies in years to come.

An extensive survey of Russell Reynolds Associates has discovered that D&I is the most determining factor of corporate culture in management. Management boards are dragging behind but achieving clear progress in the field of diversity management. What is needed now is a clear view on what kind of behavior leadership needs to exhibit to bridge the gap between observed and desired levels of diversity and inclusion. It is key to identify those managers that enable the cultural transformation in a sustainable way.

1 The importance of diversity management

The term diversity management can look back on an impressive career. It started out as a US civil and political grassroots movement in the 1960s, an amalgamation of the women’s rights and civil liberties movements. In the past decade, however, management increasingly became a business management concept, seeking to recognize diversity and utilize it for the benefit of all concerned. Specifically, diversity aims to recognize people’s varied achievements and experiences and to grasp and utilize their potential. Eliminating discrimination and promoting equal opportunities are the core objectives. Fundamental aspects representing human diversity are mostly held to be age, gender, ethnicity, social background, sexual orientation, and physical and psychological condition.

As a consequence, the turnabout in recent years regarding attempts to increase the number of female executives in businesses happened not only as a result of moral scruples: many companies realized the need for greater diversity among their leadership and workforce to guarantee their place at the top. This push for greater diversity is not only of benefit to management, by way of increased profits and employer branding, but also to employees. For example, current research supports the assertion that growth in the number of female leaders has a distinct impact on company culture and talent decisions. Talented individuals that may otherwise be overlooked have a higher chance of being developed and promoted, leadership assessments are conducted in a more objective manner, and knowledge is built across the organization through mentoring programs (Byham, 2018).

The higher the corporate level, the greater the impact of diversity is. Continuing the example of gender diversity, this year’s McKinsey Report restates that companies with greater gender diversity can hope to achieve greater profits. According to Hunt et al. (2018) companies on the lower rungs of the diversity ladder can expect sub-par results.

Moreover, companies employing a greater number of women in leadership positions are mentioned in the same breath with supreme financial performance or greater across-the-board success. When it comes to the prevailing view in the public opinion, diversity affords individuals, teams and organizations an advantage. The following advantages are often mentioned in the public debate:

- better initiation of business contacts, resulting in advantages on international markets;

- improved employer branding, following from possibilities of hiring top international talents;

- generating a better image towards clients and enhancing responsiveness to a variety of customer demands;

- better prerequisites for innovation, lower organizational blindness;

- performance enhancement through more effective teamwork, lowered chance of groupthink in teams;

- higher motivation because of higher identification of employees with their companies.

2 Diversity management in the chemical industry in the USA, Europe, and Asia

What then is the current situation in the chemical industry? In its September 2017 issue, Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN), published by the American Chemical Society, printed survey results showing that women then occupied 16.7% of 430 board director seats at 43 US chemical companies (Tullo, 2017). That was an increase of some 16% compared to the previous year.

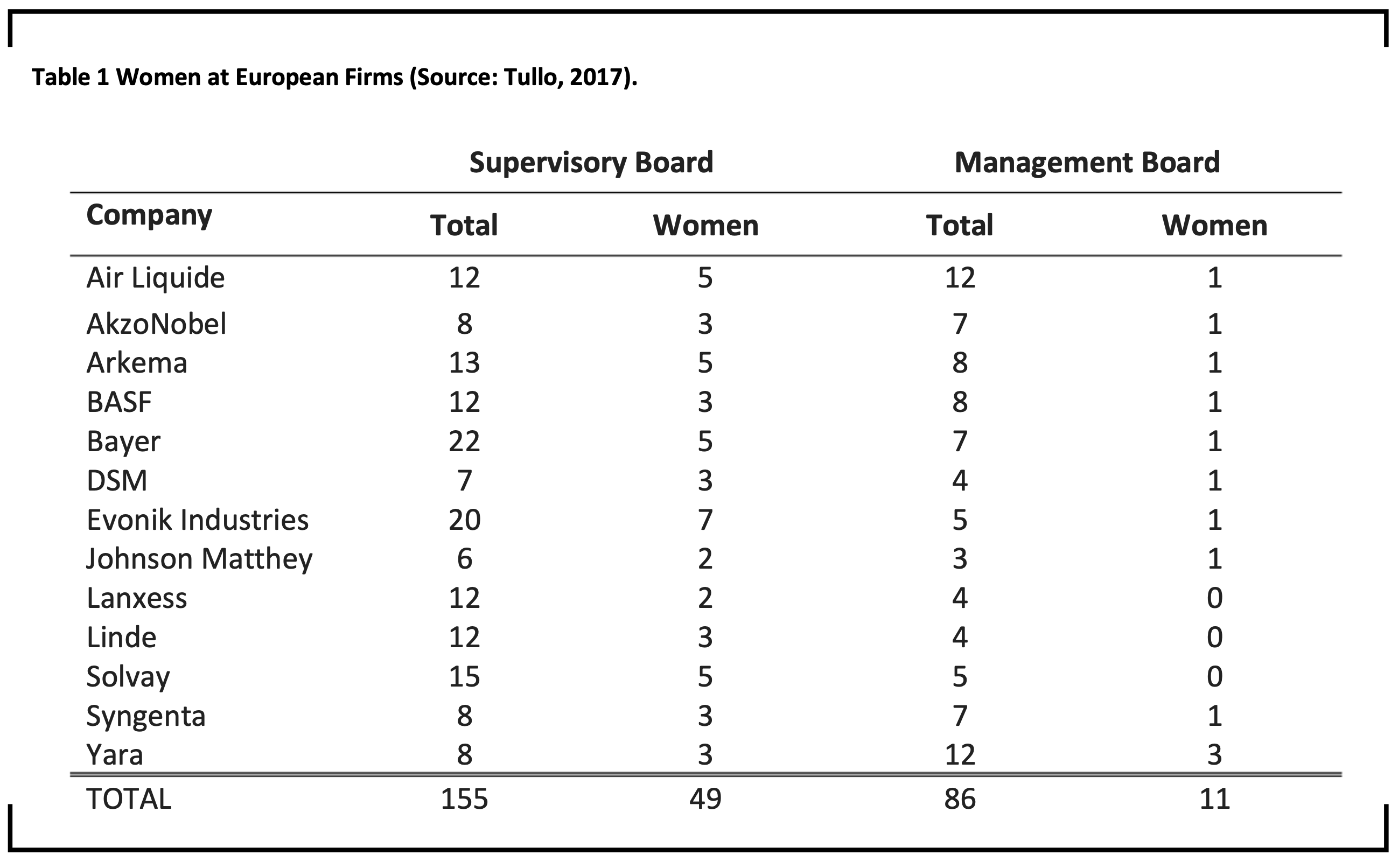

In Europe, the female top leadership share is even higher with the trend continuing upward. C&EN’s 2017 survey found that in 13 chemical companies examined, more than every fourth board seat, namely 28.6 % of 154 such seats, was filled by a woman (Tullo, 2017).

C&EN said that Europe’s trailblazers, as depicted in table 1, included Air Liquide, whose supervisory board had 5 female and 7 male members. Akzo Nobel had 3 women and 5 men on their supervisory board, as did Syngenta and Yara. DSM’s supervisory board was on its way to achieving a similar setting with 3 women currently facing 4 men.

C&EN discerned an upward trend at Bayer, BASF, Evonik, LANXESS, and Solvay, but women still are a distinct minority on the supervisory boards of these companies.

Efforts to achieve greater diversity on management boards have not been as pronounced, says C&EN. The gender ratio on management boards at Europe’s chemical giants is 7:1, i.e. seven males to one female in management – a significant difference when compared to supervisory boards, where the average ratio is 2:1 in favor of men (see table 1).

But management boards can also be proof of diversity accomplishments, as shown by the Dow Chemical Company. Dow’s 2017 annual report revealed that their executive leadership council consisted of 10 men and 5 women – the share of women was thus a third.

Some Scandinavian companies, especially Norwegian firms, have an even greater proportion of women. This could be the result of drastic regulation; even in 2004, the Norwegian governmental board gender quotas that forced all public enterprises to achieve a quota for both genders of at least 40% for all new hires. In 2006, this rule was also applied to the publicly listed companies, who were granted a 2-year transitional period. As of 2017, the share of fe- male executives in publicly listed companies has raised as high as 42.1%. The respective share of women in leadership positions across all not-listed commercial companies is “only” 18.4%, based on Statistics Norway (SSB).

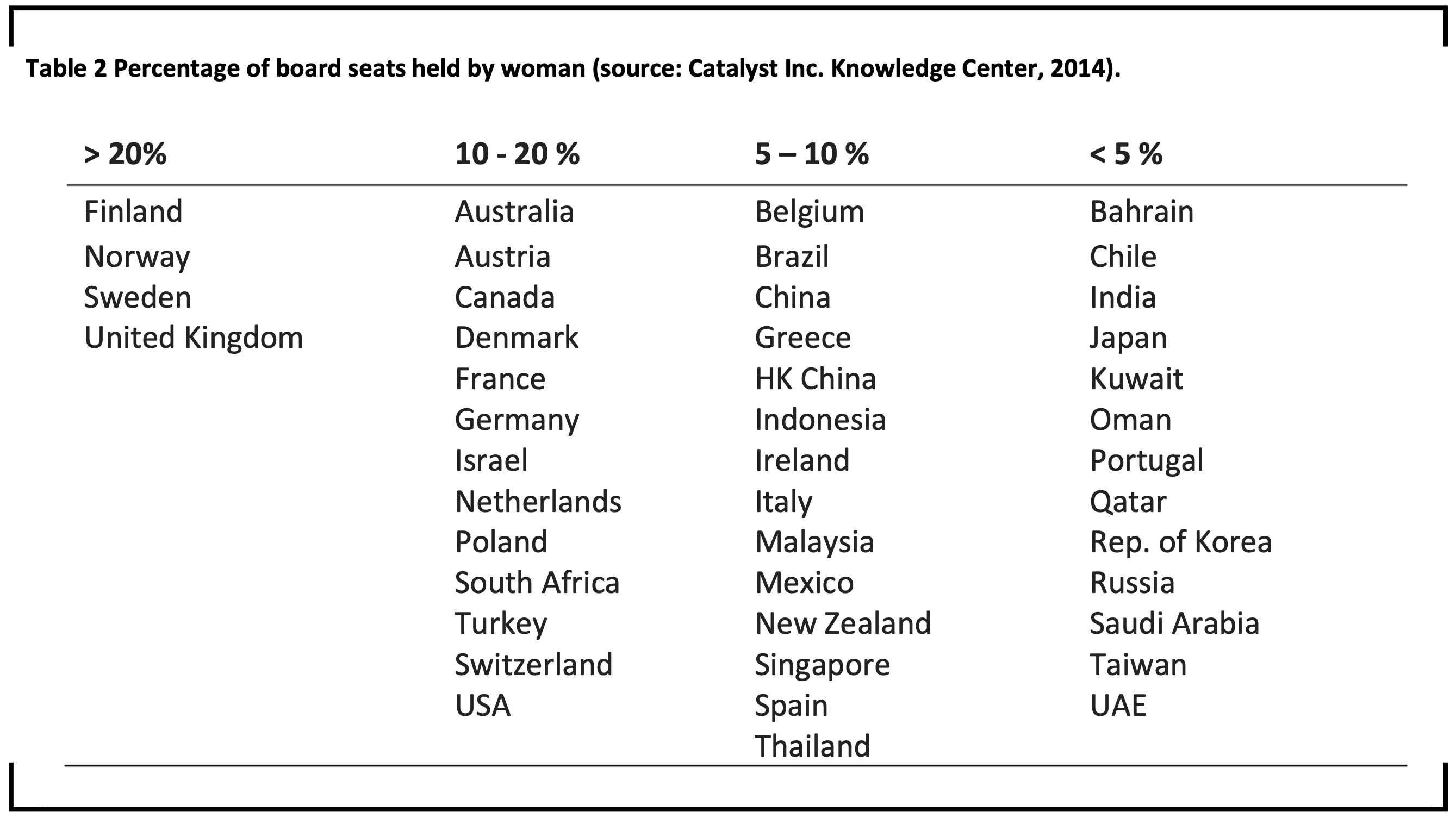

A survey on Women in Business and Management: Gaining Momentum, published by the International Labour Organization, found that Norway’s 13.3% pertaining to companies with a woman in a board seat was the highest percentage worldwide. Norway’s total number of women on boards exceeds 20%, which puts it at the top of the table together with Finland, Sweden, and the UK. At the other end, with only around 5% of women in leadership, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Chile and Japan are to be found.

Without a doubt, Norway is a diversity trailblazer, not only in Europe and in the chemical industry, but indeed globally, especially because of its comparatively stringent legal measures.

The large proportion of women in leadership in Norway is also the result of female shareholder elected board members assuming multiple board seats. To meet legal requirements, women in Norway tend to fill far more than the three board seats considered feasible for anybody holding down an operational job as manager or C-suite executive. This development, caused by the severe government-mandated regulation, is now seen very critically in Norway, too.

Looking at the German chemical industry, the BASF board consists of 6 men and 1 woman. In 2010, the board contained only men. The world’s largest chemical concern’s annual report contains this statement: “BASF views the development and advancement of women as a global duty – independent of individual group companies. To achieve this, we have set ourselves ambitious global goals and made further progress in 2017. BASF will keep working on in- creasing the share of women in the leadership team. To this end, the company is applying measures across the world and continually working on evolving them.”

Nonetheless, the road to gender equality seems to be a long one, not only at BASF, but at all German chemical companies. This opinion is expressed by the Verband Angestellter Akademiker und leitender Angestellter der Chemischen Industrie (VAA). The most recent survey in 2015 of 2,000 executives showed that women were represented in leadership positions much less frequently than men, even if they had the same qualifications and the same age (VAA, 2015).

Despite similar ages and qualifications, the VAA criticizes that only 26% of women interviewed were executives in their companies while that figure for men stood at 36%. Gender inequality was particularly significant in higher positions like departmental heads, managing director’s (MDs), or board members. Only 4% of women had such jobs, while the number for men was more than double that at 9%. The survey also examined and checked variables like age, education, time at the firm, and job content specifics.

The professional portal produktion.de provided the information that in 2015 only three of the leading German chemical companies achieved the 30% women quota, which was written into law the next year. The research institute Statista looked at the number of women on supervisory boards in the chemical industry in 2015 and found that none of the top ten achieved parity, but all had at least 25% of women serving as supervisory board members.

There is not much solid information on the diversity situation at Asian companies at present. In April 2018, McKinsey’s Global Institute criticized that across all industries, even in the developed Asia-Pacific economies, not many women managed to advance into companies’ top echelons. In Japan, said McKinsey, there were no female CEOs “in the top 100 public companies”. In Australia and Singapore, female CEOs made up 6% and 5%, respectively, in 2016. The Philippines – traditionally a matriarchal society – also only achieved a 3%-share in female CEOs and 15% in board members.

3 The Russell Reynolds Associates survey

The need for Diversity & Inclusion (D&I) is substantial and growing in all industries, including chem- ical companies. This finding was substantiated in a Russell Reynolds Associates (RRA) survey called Diversity & Inclusion as Key Success Factor of Corporate Culture, conducted in 2016 by Dr Joachim Bohner, Ms Franziska Funk, Ms Saskia Schwering and Dr Thorsten Bauer. This survey went beyond looking at diversity as tied to demographics such as gender, but rather as a holistic concept, incorporating both visible demographics as well as more implicit aspects such as diversity of thought, willingness to engage in true debate, and openness to different employee needs.

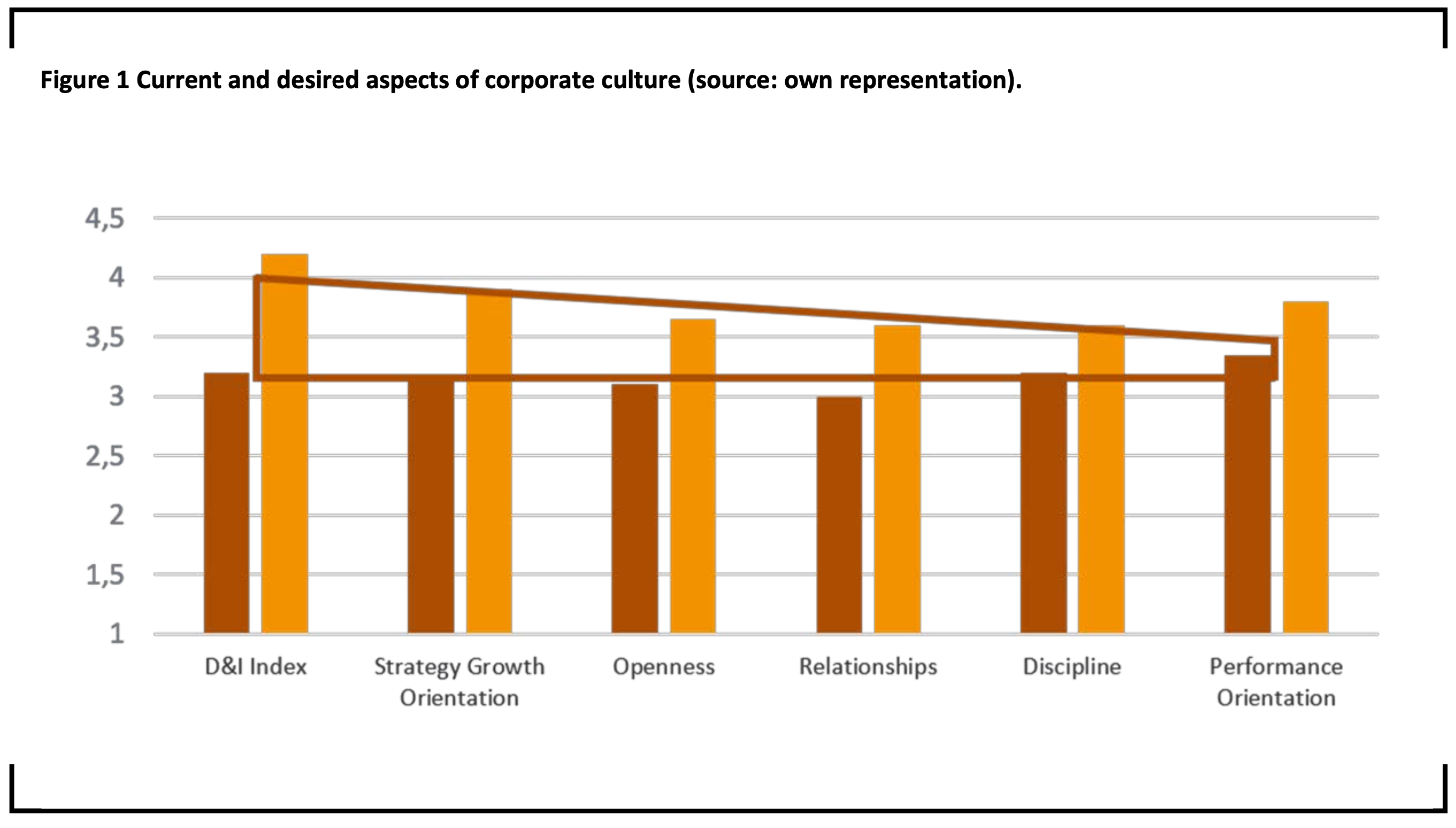

They analyzed the responses of more than 5,000 executives and arrived at meaningful results regarding the current and future significance of diversity in companies. The findings are based on the online-assessments (Culture AnalystTM) about the perceived current culture, and the desired culture crucial for the future strategic success of the assessed managers’ respective company. In total, the authors analyzed data from 119 companies.

Importantly, diversity was not only valued by managers – it was the key area that presented a need for a real and lasting change in corporate culture. The RRA survey showed that diversity and an inclusive management approach are “the most desired factor” of corporate culture compared to all other dimensions (see figure 1). Interestingly, it also presented the largest gap between current perceptions and desired levels of D&I. The researchers concluded that D&I is a key aspect of company culture has been vastly undervalued to date. To close this gap, leadership needs to consider what can be done to bridge the current and desired levels.

These results confirm the findings of the afore-mentioned studies, showing that companies with a strong diversity culture have a considerable advantage in hiring and retaining qualified staff – they are deemed more attractive employers than companies not paying much heed to diversity. In addition, these results accentuate the magnitude of im- portance of Diversity & Inclusion compared to all other factors that make up a corporate culture. This striking insight is still often underestimated in its consequences. Looking ahead, most executives now expect their companies to focus on implementing D&I initiatives with more tenacity, meaning they see this topic as the area with the largest need for attention. This makes D&I the central aspect to focus on when transforming corporate culture.

How to address the need for a change in corporate culture? Start at the top, by identifying and promoting those leaders who can bring D&I to life. In the past, organizations have invested time, money and resources in communication, training, and development methods that are not aligned with the necessary leadership requirements of today to foster D&I. Numerous analyses done by Russell Reynolds Associ- ates have shown that old, out-dated recruitment and promotion methods and one-dimensional evaluation screens no longer suffice: they cannot adequately predict a top manager’s chances for success. What is needed in today’s ever-changing and dynamic world is the ability to make best use of diversity in all its forms, leveraging these differences in an inclusive way, and thereby staying abreast of the changes in, and exponential complexity of the business.

Selection was – and often still is – based on how sizeable the performance drive is, how pronounced strategic skills and persuasive prowess are. Executives were cultivated and deemed champions of future success because they had the attributes believed to be vital: great dedication and commitment, straightforwardness, resilience, power, and intelligence. Obviously, these factors are not suddenly unimportant, but anybody wanting to be and stay successful can no longer afford to lead based on these one-dimensional qualities or rely solely on past strengths or assets.

A new kind of manager is needed, one that can join, link, unite and process internal paradoxes. This new manager must advance heroically while remaining vulnerable, in as much as s/he must be able to question herself/himself. S/he must be prepared to take risks but must also be hesitant without, however, always wanting to defensively justify what was done. Permanent introspection is required, as is a willingness to reflect on whether the propensity to take risks may be too great and could endanger the company. The new manager must be strategically minded and sufficiently pragmatic to facilitate synchronising elevated targets with the company’s capabilities. Overall, managers must be able to adjust to different situations and employ seemingly contradictory styles based on the problem at hand. What enables the new manager to bridge these gaps is having a diverse and multi-faceted personality.

When thinking through this concept of a leader with a diverse personality to its conclusion, one finds that such leaders can have the kind of effect on corporate culture that will be crucial for future success. They can create a “diversity of thought” culture, which many analyses (among them studies done by Deloitte, McKinsey, or the Harvard Business School) have determined to be the most important future success factor for companies. The ability to think and operate diversely encourages and benefits the D&I aspect in all its facets. On this topic, Dr Joachim Bohner, managing director for leadership and succession at RRA, carried out intensive research. Leaders with diverse personalities in top-management teams, that can and will create diverse corporate cultures, are accordingly every company’s most crucial element in achieving and ensuring a successful future.

References

Byham, T. (2018): Five Ways Gender-Diverse Companies Stand Out. Retrieved, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/ forbescoachescouncil/2018/08/10/five-ways-gender-diverse-companies-stand-out/#32d6bf34675a, accessed 8 October 2018.

Hunt, V., Prince, S., & Dixon-Fyle, S. (2018). Delivering Through Diversity (Rep.). McKinsey&Co. ac- cessed 8 October 2018.

International Labour Organization (2015): Women in Business and Management Gaining Momentum , available at https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/ groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_334882.pdf, accessed 8 October 2018.

Nishii, L. H. (2013): The Benefits of Climate for Inclusion for Gender-Diverse Groups. Academy of Management Journal.

Noyan, B. (2017): The 100 Best Workplaces for Diversity 2017, available at http://fortune.com/best-workplaces-for-diversity/, accessed 8 October 2018.

Sinar, E., Paese, M. (2018): Leaders in Transition Progressing Along a Precarious Path [Scholarly project], DDI World, available at https://www.ddi-world.com/DDI/media/trend-research/lead- ersintransition_tr_ddi.pdf?ext=.pdf, accessed 8 October 2018.

Tullo, A. H. (2017): Women in the chemical industry 2017, available at https://cen.acs.org/articles/95/i36/Women-chemical-industry-2017.html, accessed 8 October 2018.

Why Diversity Matters. (2013), available at https://www.catalyst.org/system/files/why_diversity_matters_catalyst_0.pdf, accessed 8 October 2018.

Why Is It Important To Maintain Gender Diversity at the Workplace? (2018), available at https://www.theflexiport.com/blog/ view/199 /why-gender-diversity-at-the-workplace, accessed 8 October 2018.

Zenger, J., Folkman, J. (2014). Are Women Better Leaders than Men?, available at https://hbr.org/ 2012/03/a-study-in-leadership-women-do, accessed 8 October 2018.