The benefits of social sustainability reporting for companies and stakeholders – Evidence from the German chemical industry

Companies’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities respond to the increasing expectations of society. One of the three dimensions of sustainability, also known as the triple bottom line, is social sustainability. Compared to economic and environmental sustainability, the social dimension is often neglected by companies. Especially actors in the chemical industry are having a great social responsibility and are thus constantly monitored with regard to their activities and performance. Consequently, the firms need to care for their social sustainability in order to secure their license to operate. This study therefore aims at identifying the current state of social sustainability reporting within chemical companies in Germany. A data set of 14 CSR reports is tested regarding the use and fulfillment of the Global Reporting Initiative’s (GRI) guidelines and indicators regarding social aspects. The results clearly indicate that social sustainability reporting is handled quite diverse concerning structure and extent among the analyzed companies. The study concludes with recommendations of how to improve the comparability of social sustainability reporting for internal and external use.

1 Introduction

CSR is a holistic term for “actions of firms that contribute to social welfare, beyond what is required for profit maximization” (McWilliams, 2015, p. 1). Integrating sustainable actions into the core business comes into focus and is frequently discussed as the business case for sustainability (Dyllick and Hockerts, 2002; Epstein and Roy, 2003; Salzmann et al., 2005; Schaltegger and Hasenmuller, 2005). CSR is supposed to cover the so-called triple bottom line including the dimensions economic, environmental and social sustainability (Elkington, 1997; GRI, 2011). The implementation of standards in each of these dimensions becomes more and more important for companies, particularly in Western countries (McWilliams and Siegel, 2001; McWilliams et al., 2006; Potts et al., 2014). While many guidelines concerning economic and environmental sustainability have been introduced over the past decades, e.g. for the chemical industry (Gladwin et al., 1995; Hart, 1997; Hoffman, 1999), the implementation of social sustainability is still seen as challenging by the industry (CEFIC, 2014; VCI, 2013).

“Social elements relate to employment characteristics (e.g. diversity of people employed, labor rights, training) and community relations” (Epstein and Roy, 2003, p. 84) and thus address the internal staff on the one hand and the external society on the other. These aspects are of particular importance for the chemical industry (CEFIC, 2014). The safety and working conditions for the internal staff are crucial to ensure the employability of the work force (VCI, 2013). Further, it is an important asset in recruiting new employees, where chemical companies face a strong competition for skilled workers within and across industries (CEFIC, 2014). On top of protecting their human capital, chemical companies invest in further education of their staff (Robertson and Nicholson, 1996). The gap in gender equality among the workers of chemical companies is an additional field that needs to be addressed by organizations within their CSR initiatives.

At the same time, the chemical industry needs to build and maintain trust among the public to secure their license to operate (Hoffman, 1999). In addition to their environmental activities such as reducing the pollution caused by their products and processes and their economic activities providing secure employment and contributing to initiating local economic growth, chemical companies also need to show social engagement. Thereby, they can improve their image as an employer or business partner and create acceptance in the local society. To communicate sustainable activities effectively, many companies use reporting as an instrument. CSR reports have the advantage of documenting contents of sustainability activities in detail and presenting intangible social aspects of a company’s behavior (Porter and Kramer, 2006).

While research on CSR reports often discusses the overall advantages and disadvantages of sustainability activities and their reporting, the two questions addressed in this paper concentrate on the specific nature of social sustainability reporting:

- Which social sustainability aspects are most relevant for companies and why?

- How do social sustainability reports differ and what influence results on stakeholder benefits?

In order to discuss these questions, 14 CSR reports are analyzed with regard to social sustainability indicators suggested by the GRI. To shed light on the question of relevance of social sustainability reporting for German chemical companies, the potential motivations as well as the goals of sustainability management reported by the companies are gathered and compared to the reported indicators. Further, the usage of guidelines and participating in initiatives is analyzed.

The second question addresses the differences in social sustainability reporting across companies and the benefits of social sustainability reporting for stakeholders. In order to respond to the question, the content and scope of reported sustainability aspects are first analyzed qualitatively. The companies’ CSR reports are summarized according to their fulfillment of single performance indicators suggested by the GRI guidelines. Furthermore, identified gaps in reporting are critically discussed based on the reasoning given in companies’ reports and in order to highlight the problems for stakeholders in interpreting social responsibility reports.

2 Theoretical background

In order to understand the background and analysis of the posed questions, it is necessary to characterize the concept of sustainability from a business perspective. Therefore, the following section describes the principle and different elements of sustainability at a corporate level. Subsequently, the special position of the social dimension is depicted and sustainability reporting is presented as a key instrument of sustainable activities.

2.1 Defining sustainability at the corporate level

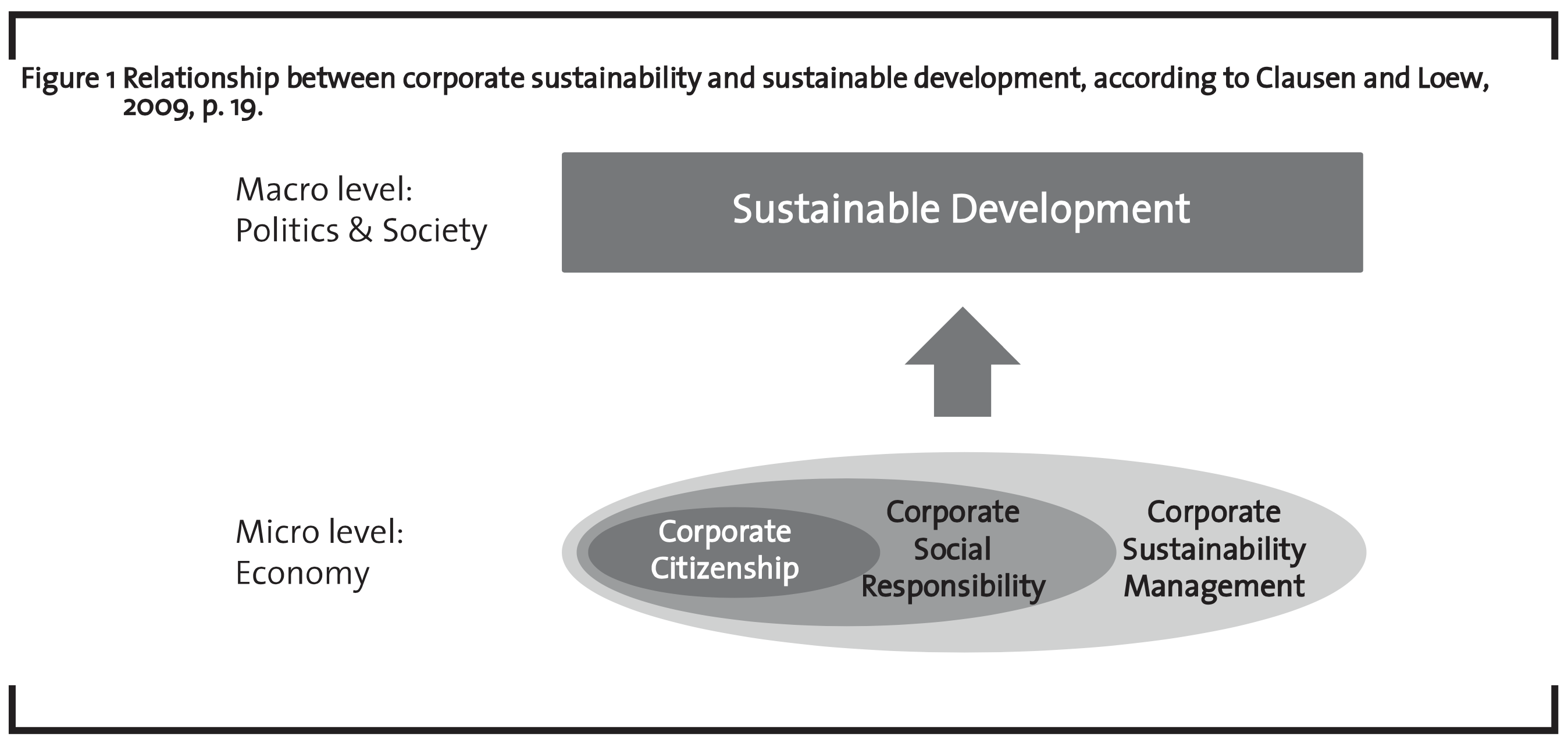

Sustainability is a holistic concept that applies to politics and society as well as industry (Clausen and Loew, 2009; Loew and Rohde, 2013). Accordingly, the principle of sustainability is used at the macro level as well as the micro level. The latter represents the company level and thus the contribution of enterprises and in particular their CSR initiatives to sustainable development (Clausen and Loew, 2009) as illustrated in figure 1.

Sustainable development refers to the overall impact of sustainable action and was initially only characterized as responsible use of natural resources (Beddoe et al., 2009; Jahn et al., 2013). Discussions on sustainability are still shaped by the definition presented within the so-called Brundtland Report of 1987: “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” (UNGA, 1987, Chap. 2, §1). The concept addresses the three dimensions economy, ecology and society, also referred to as the triple bottom line indicating the dimensions to be interlinked and implemented together (Elkington, 1997). On the company level, this means that all three levels should be integrated into operations and handled equally.

From a business perspective, enterprises shape the ecological and social environment with their economic actions (GRI, 2013). In addition to operationalizing their business goals, aspects of sustainability need to be considered and integrated with various functional areas. In particular, this includes risk management, human resources management, innovation management and strategic management (Figge et al., 2002; Loew and Braun, 2009; Schaltegger et al., 2007). An entrepreneurial model of sustainability can only be effectively implemented if the sustainable concept is anchored in core business. The top management should be encouraged to make a business case for sustainability to increase financial performance and competitive advantages in the long term (Salzmann et al., 2005; Weber, 2008). Sustainable measures oriented toward economic goals are seen to be the key to significantly contribute to corporate success (Orlitzky et al., 2003; Salzmann et al., 2005; Weber, 2008).

2.2 Corporate social sustainability

The implementation and organization of sustainability-related management approaches requires a comprehensive understanding of the dimensions of sustainability as well as their respective risks and opportunities (Dyllick, 2003; Haasis, 2008). In this context, it is often criticized that insufficient attention is put on the social level of CSR and that it is rather unconsciously involved in strategic measures (Bostrom, 2012; Dyllick and Hockerts, 2002; Heins, 1998; Vallance et al., 2011; Wagner and Henle, 2008). In many companies, ecological activities still constitute the focus of sustainable activities. However, the increasing pressure from external stakeholders urges firms to more social responsibility at all levels in order to ensure safety. Particularly the chemical industry is obliged to include aspects of social sustainability in their business strategies and activities. This presents a challenge for enterprises as social sustainability is mainly based on intangible components and includes aspects that cannot or rarely be visualized by indicators (Jorissen et al., 1999). This fact complicates to control for social aspects and to measure their impact.

Social behavior is anchored in social norms and values and aims to assure socially relevant needs. Human dignity, justice and prosperity are the foundation of social sustainability in order to ensure better living and labor conditions in the future (Bundestag, 1997). Major issues of corporate social sustainability are for example ensuring diversity and equal opportunities, health and safety, fair competition, and preventing forced or child labor and corruption. Enterprises are encouraged to address all social spheres of activity, i.e. labor practices, human rights, product responsibility and society in its entity (GRI, 2011).

Social sustainability measures need appropriate resources. These resources mainly emanate from the intangible capital of social and human values that must be generated and accumulated by enterprises (Dyllick and Hockerts, 2002; Spangenberg and Bonniot, 1998). Thereby, social capital sets the society as a whole into focus, while human capital refers to the single individual. Thus, the employees and the social environment compose the center of business operations (Goodland, 2002; Spangenberg and Bonniot, 1998).

Overall, the challenge for enterprises is to satisfy social needs resulting in social acceptability and legitimacy (Perrini and Tencati, 2006; Porter and Kramer, 2006). Enterprises can thus benefit from living social sustainability, particularly through an improved reputation and image.

2.3 Guidelines for and reporting of sustainability aspects

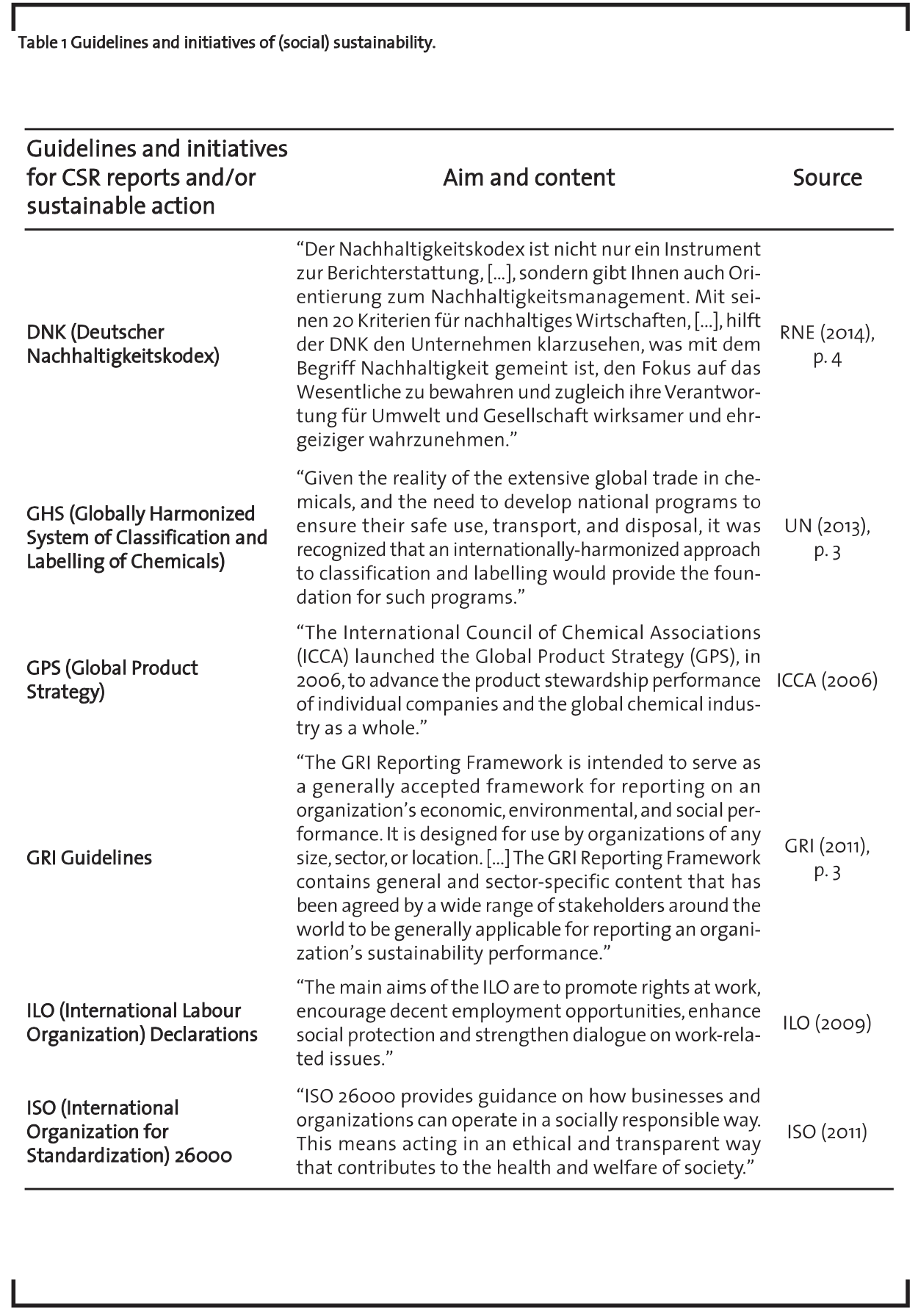

In the European Union, CSR is based on a voluntary approach and can be integrated into business activities and practiced in various forms (Commission of the European Communities, 2001). Companies are confronted with many different guidelines and initiatives for their sustainable activities. Regulations and assistance for the implementation and fulfillment of CSR measures exist at both national and international level and are established by different organizations. In addition to widely recognized guidelines for sustainability reporting, e.g. by the GRI, there are also international documents challenging companies for corporate responsibility in terms of human rights or labor safety. For the chemical industry, sector-specific initiatives focusing on corporate social and ecological responsibility, safety and sustainability are also relevant. Table 1 shows the most important guidelines and initiatives affecting the German chemical industry.

Although companies can choose of a variety of guidelines, the social aspects and practices of sustainability often remain neglected as their economic benefit is often not visible or measurable, at least not in the short-term (Jorissen et al., 1999; Schaltegger et al., 2007). Hence, seized CSR measures mostly result from a sense of moral or legal obligation. The increasing force from external stakeholders drives companies to more social responsibility and a social culture. At the same time, corporate actions provoke reactions from stakeholders and influence them in turn. Epstein and Roy (2003) describe this relationship as follows: “[…] sustainability performance and actions are drivers of stakeholder reactions. It is through stakeholder reactions that managers can accurately translate actions and performance into the resultant costs and benefits. Furthermore, stakeholder reactions provide feedback to revise corporate strategy […].” (Epstein and Roy, 2003, p. 82).

Therefore, the stakeholder concept introduced by Freeman (1984) attracts specific interest in the field of CSR. It describes the reciprocal relationship between businesses and societal stakeholders. All stakeholders have a common interest in transparency and an open communication of the implemented sustainability measures and performance of companies (Perrini and Tencati, 2006). The involvement of stakeholders’ interests in sustainable decision-making processes is of fundamental importance (GRI, 2011; Perrini and Tencati, 2006) in order to minimize wrong choices at an early state, increase corporate success and ensure authenticity and acceptability (Hauth and Raupach, 2001; Hentze and Thies, 2014).

Reporting can be considered as an essential instrument of sustainability communications (Hentze and Thies, 2014). CSR reports enable companies to satisfy information requirements of relevant stakeholders and at the same time involve the stakeholders actively in their business decisionmaking processes (Perrini and Tencati, 2006). The economic benefit of a CSR report consists in both controlling and exerting a positive influence on the employees. These reports are as well supposed to facilitate benchmarking between companies.

Summing up, the internal benefits of sustainability reporting according to GRI (2014) are:

- developing vision and strategy on sustainability

- improving management systems, internal processes and setting goals

- identifying strengths and weaknesses

- attracting, motivating and retaining employees.

External motivations and potential benefits are:

- enhancing reputation, achieving trust and respect

- attracting funding

- increasing transparency and dialogue with stakeholders

- achieving competitive advantage and leadership.

An overall goal of sustainability reporting for companies, especially in B2B markets, is a good sustainability rating (as provided by different sustainability rating providers, i.e. by Johnson Controls Inc. or EcoVadis SAS) to satisfy the demands of customers, suppliers (Foerstl et al., 2010; Freeman and Velamuri, 2008; Lamberti and Lettieri, 2009) and institutional investors (Campbell, 2006; Wahba, 2008). However, besides these externally motivated goals there are further goals companies pursue by their sustainability reporting. Especially for the social sustainability activities in the chemical industry, these internal motivations are of higher importance and at the same time not as clear as ecological or economic motives.

For preparing and implementing a CSR report, companies primarily rely on the GRI guidelines. The GRI specifies those reports as follows: “Sustainability reporting is the practice of measuring, disclosing, and being accountable to internal and external stakeholders for organizational performance towards the goal of sustainable development.” (GRI, 2011, p. 3). Besides the successful implementation of sustainability strategies, the disclosure of shortcomings and complications should be part of a transparent report. It should be a balanced and reasonable representation of the sustainability performance (GRI, 2011).

3 Empirical evidence

3.1 Research approach

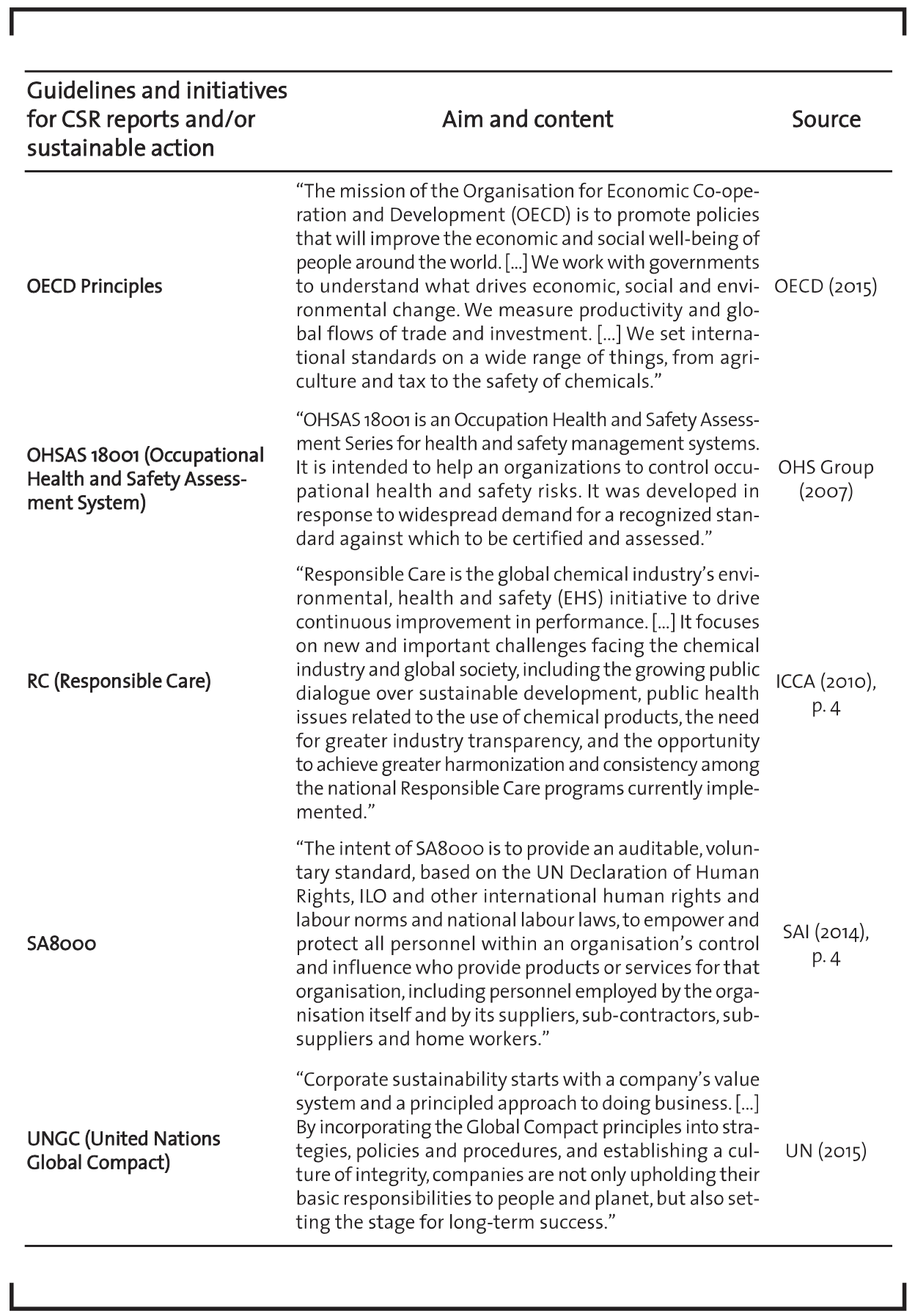

A sample of 14 CSR reports from German chemical companies for the year 2013 is collected from the GRI database (GRI, 2015). These reports have been submitted according to the sustainability reporting guidelines (version 3.0 and 3.1) issued by the GRI. For companies that publish reports in a twoyear rhythm, the most recently available publication has been selected. The CSR reports are first investigated qualitatively regarding their contents and then quantitatively based on their fulfillment of social performance indicators by the GRI. Information on the companies is provided in table 2.

3.2 Discussing the results regarding qualitative content analyses

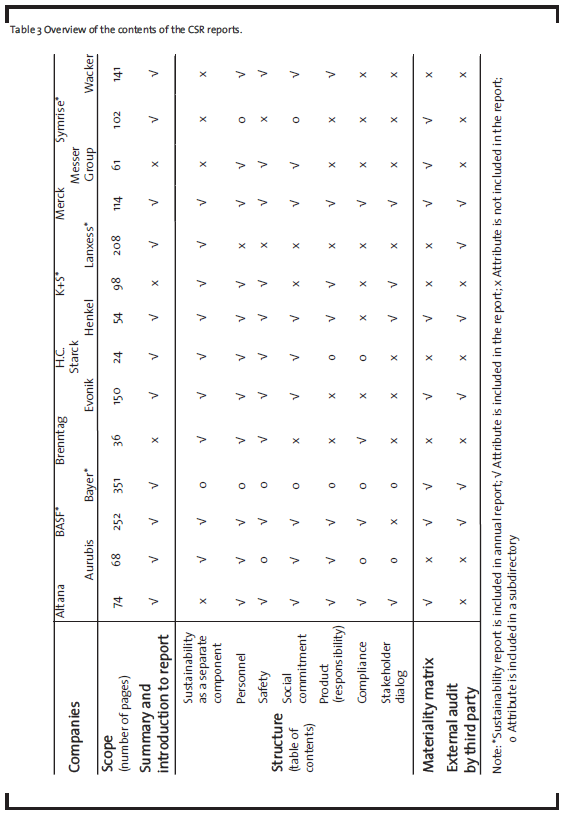

The CSR reports of the 14 companies are firstly compared according to their extent and structure. Table 3 provides an overview about different attributes and specific social topics included in the table of contents in the reports of the analyzed companies. The analysis of the reporting structure, i.e. the table of contents, does not allow drawing conclusions on the absence of any sustainability issues in the full report. However, as the table of contents gives a quick outline for interested readers where to find relevant information, it makes the report an easy to use document for stakeholders.

It can be seen that many CSR reports miss to address certain social topics in their table of contents. For instance, substantial attributes recommended within the GRI guidelines are partly absent. Further, a materiality matrix is missing in 6 of 14 reports. A materiality matrix is the graphical presentation of essential sustainability aspects which companies identify for themselves as relevant and are willing to report. Thus, reports are not consistent in their composition across companies. Additionally, only 6 of the 14 reports have received an external audit by a third party.

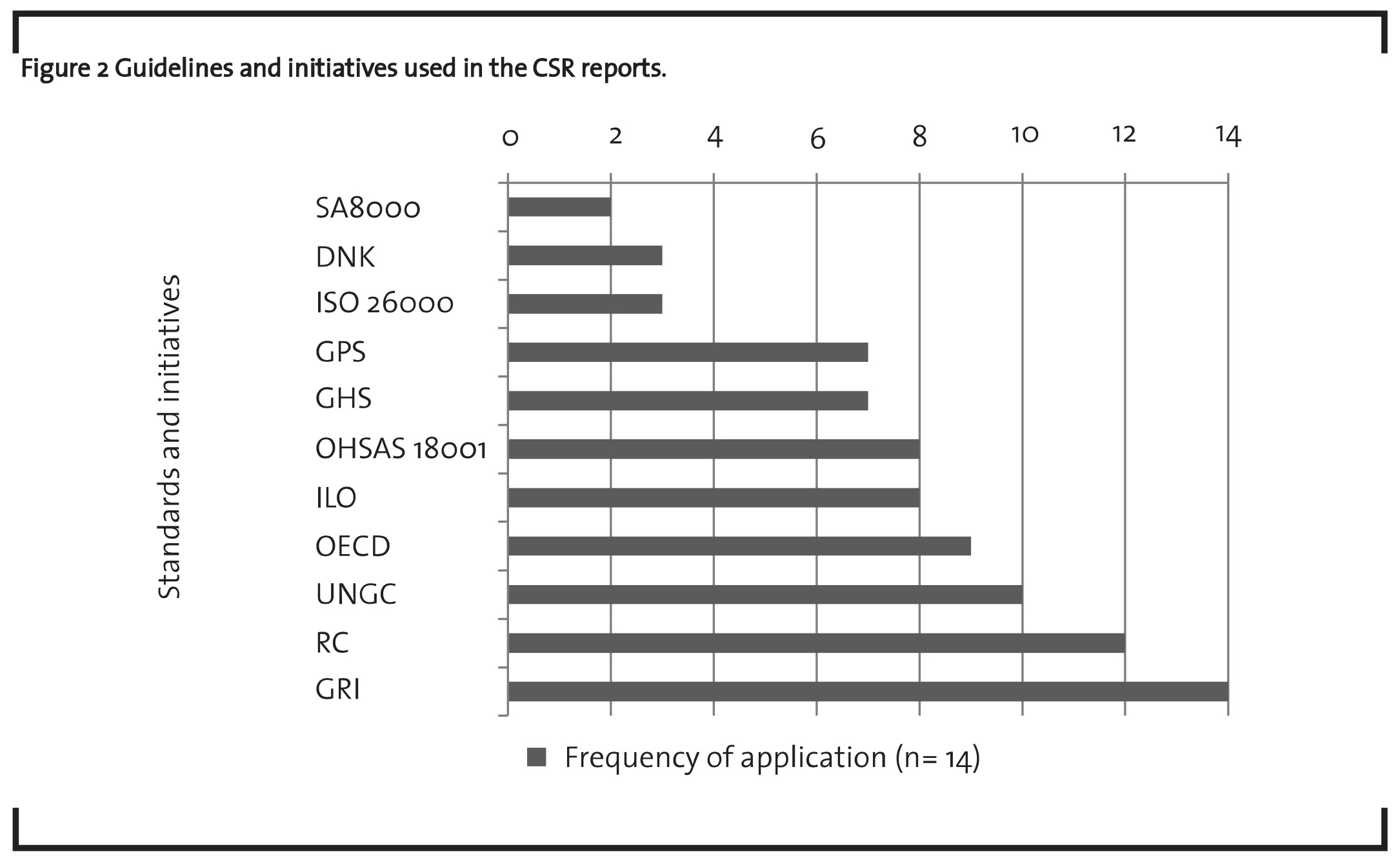

The reports have as well been examined in terms of being in conformity with the different guidelines and initiatives for corporations displayed in table 1. Figure 2 shows the frequency of application of the different guidelines detected by a keyword search within the CSR reports. Due to the data source, all reports use the GRI guidelines and most of them include voluntary commitments, such as the chemical industry’s RC initiative mentioned in 12 of 14 cases. More than 70% of the companies state that they commit themselves to the 10 principles on human rights, labor standards, environmental protection and fight against corruption codified in the UNGC. Concerning the responsibility for products and services, half of the companies follow the GHS or GPS. Only little use is made of the ISO 26000, SA 8000 and the German sustainability codex (DNK).

The usage of different guidelines might result from the various goals the reporting companies want to achieve with their reporting. Therefore, a closer look is taken on the purposes stated in the CSR reports. Unfortunately, not all of the 14 companies state their aims of sustainability management as recommended by the GRI guidelines.

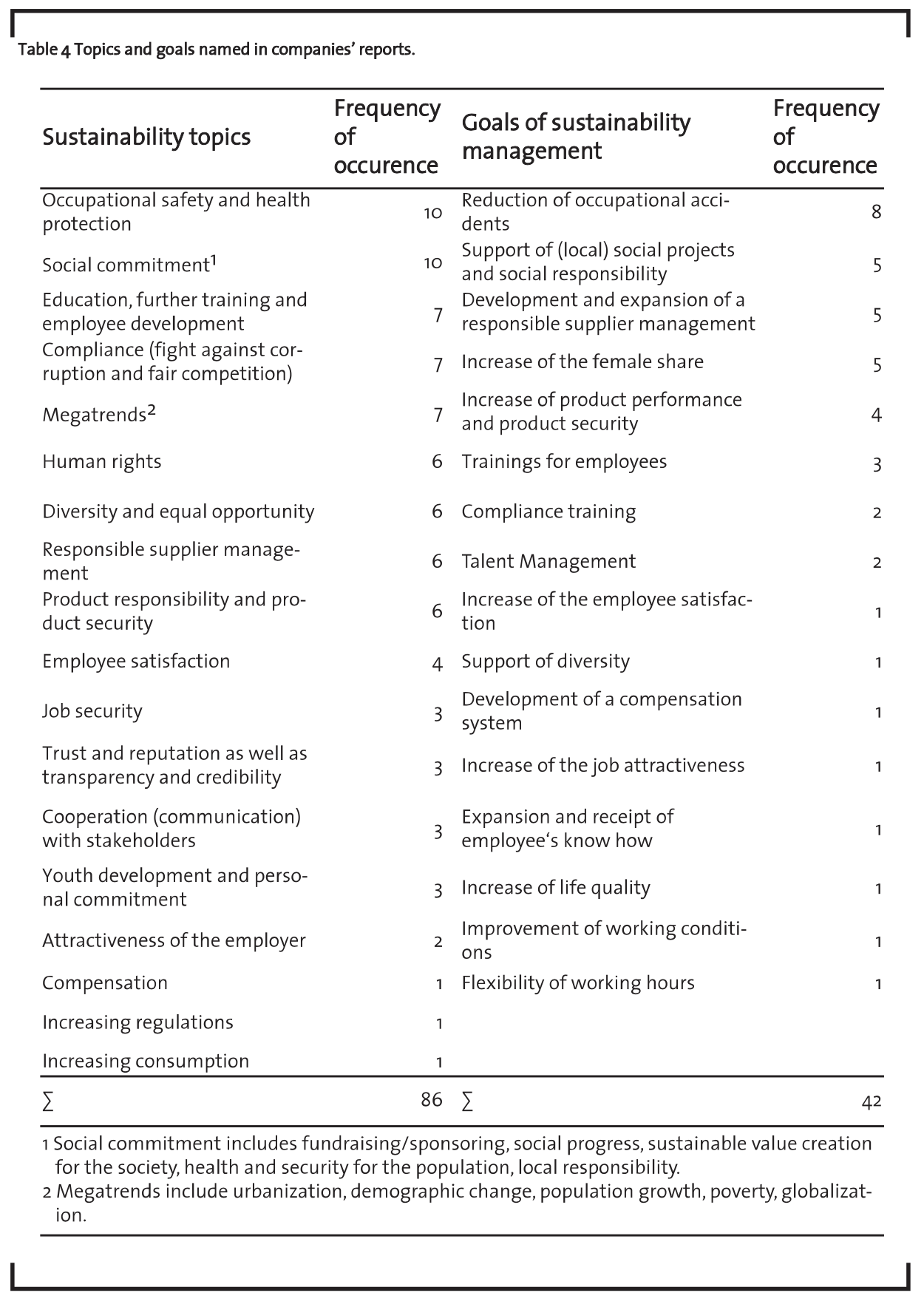

3.3 Results concerning the fulfillment of social indicators

Ten companies comply with the GRI classification of relevant sustainability topics. Nine of those reports also list the goals of their company’s sustainability management. Table 4 shows the prevalence of topics and goals among German chemical companies. The topics work safety and social commitment are named in every report of the sample and therefore seem to play a central role in social sustainability management. The reduction of work accidents and support of social projects are some of the most mentioned goals. Overall, the goals and major topics named in the CSR reports seem to be aligned in all reports in the sample. Goals like the support of social projects are displayed in the report when elaborating on social commitment like sponsoring and local responsibility. The same is true for responsible supplier management, fostering diversity and equal working opportunities and the further training for employees.

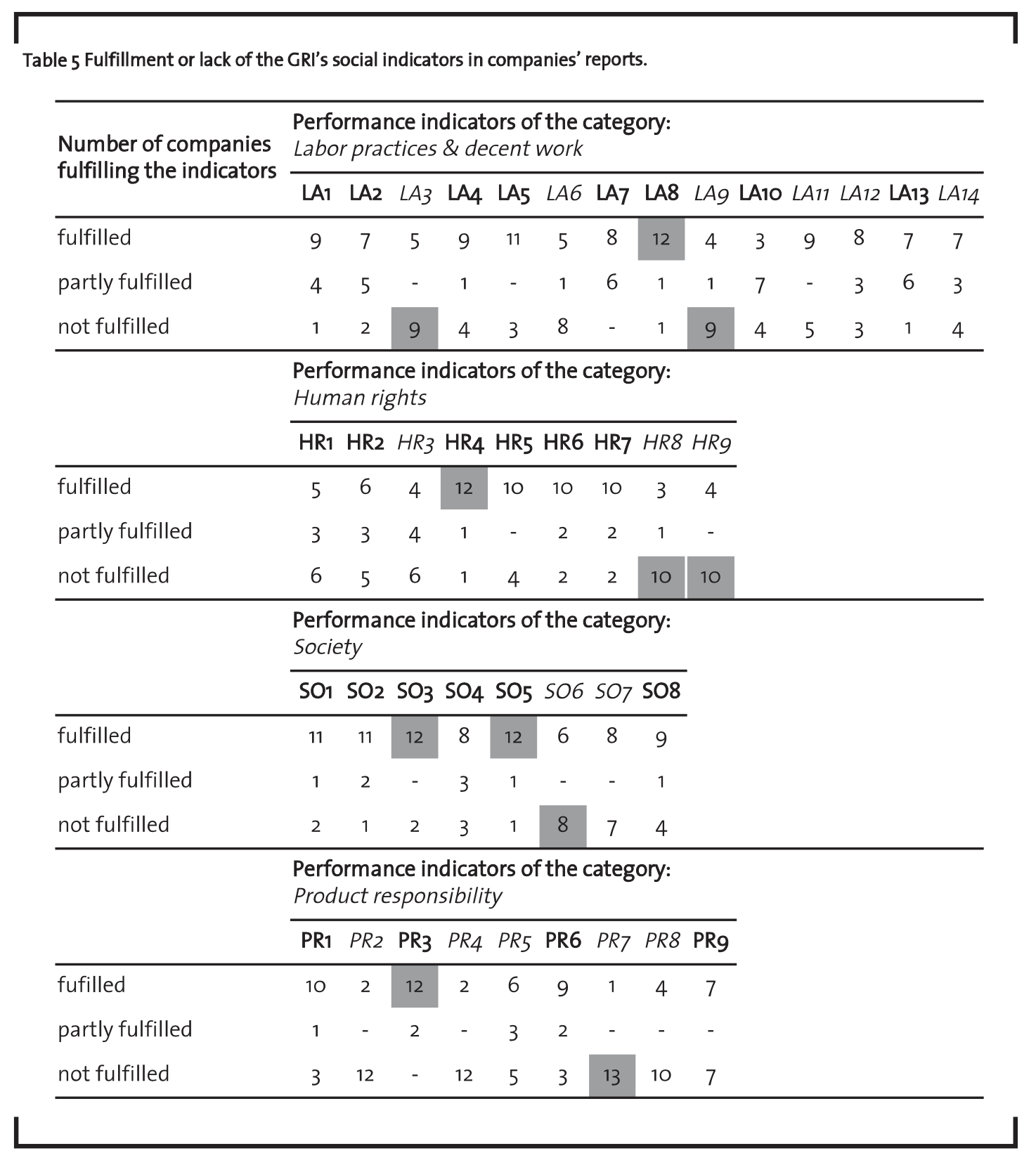

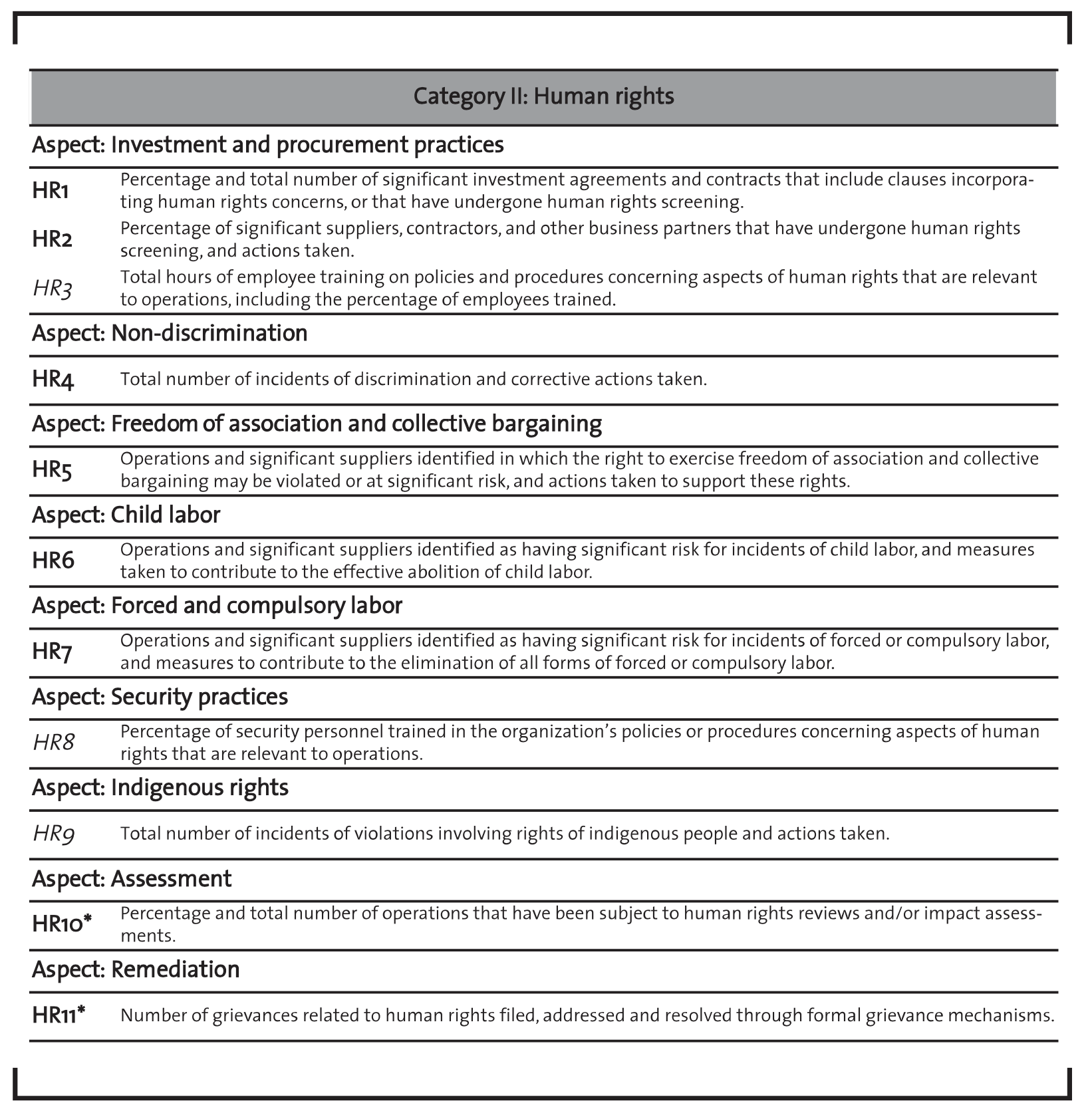

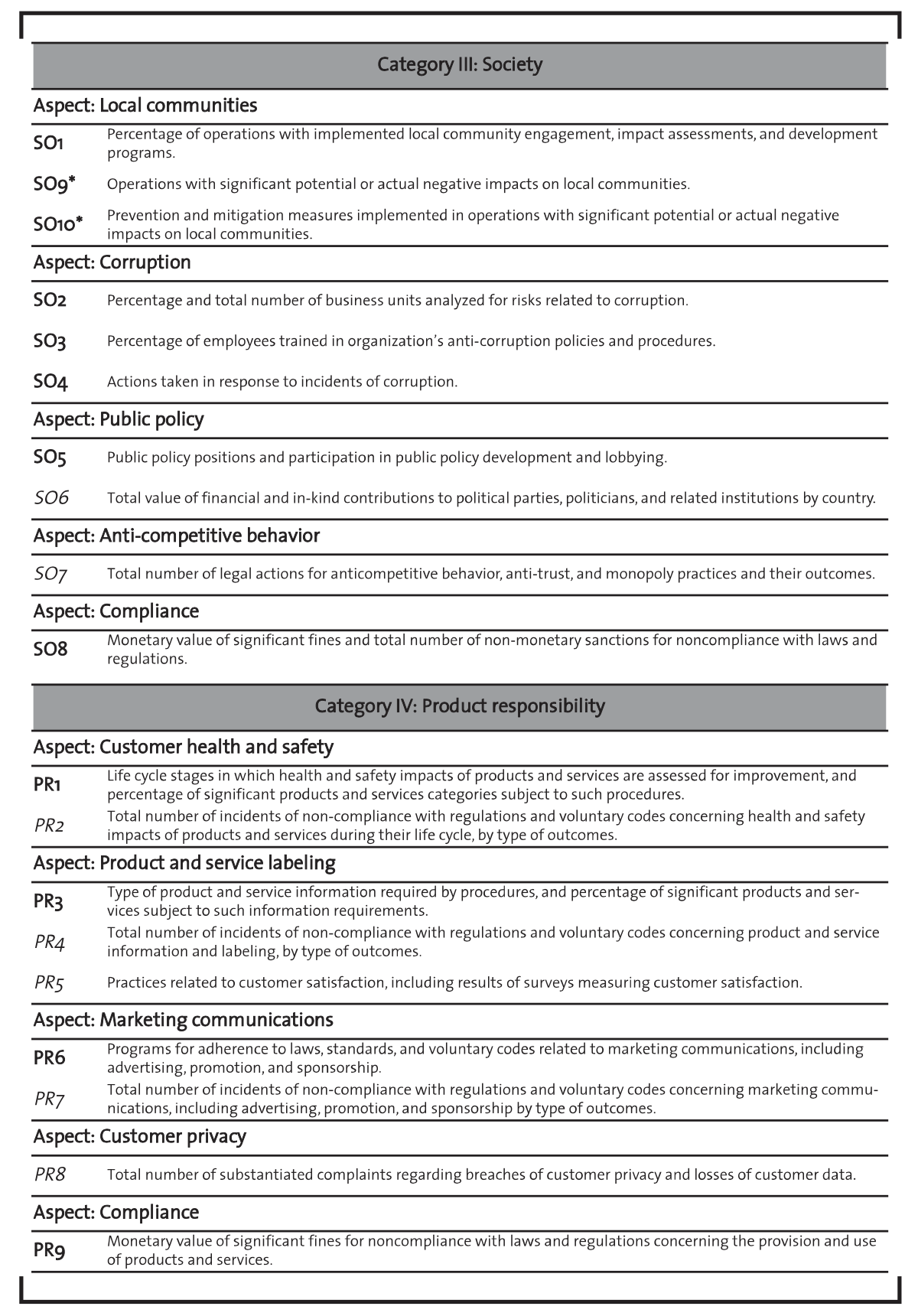

Table 5 provides an overview about the fulfillment of indicators organized by categories according to the GRI guidelines (only indicators that are included in both version 3.0 and 3.1 are analyzed). Definitions for every indicator are included in the appendix and sorted by the categories labor practices and decent work, human rights, society and product responsibility. The most frequently fulfilled indicators for each category are highlighted in grey in the respective columns.

It has to be kept in mind that some indicators are core indicators (bold) and some indicators are designated as additional indicators (italic). The analysis shows that core indicators are more often fulfilled than additional indicators, which are reflecting emerging practices or topics only affecting some organizations. However, it is striking that none of the core indicators is met by all 14 companies in the sample. Another issue is that “fulfillment” of an indicator is not necessarily enabling a valuation of a company or pointing to a “good” social performance, but only indicating the provision of the required information.

From a total of 350 core indicators in the sample, 65% are fully reported. The percentage of reported additional indicators (n= 210) sums up to only 34%. More than half of the additional indicators (60%) are not considered in the social sustainability reports under analysis. The share of reported core indicators in relation to the total number of indicators (n= 560) is 40% and 13% for fulfilled additional indicators. The low values indicate that the additional social indicators have little relevance for companies.

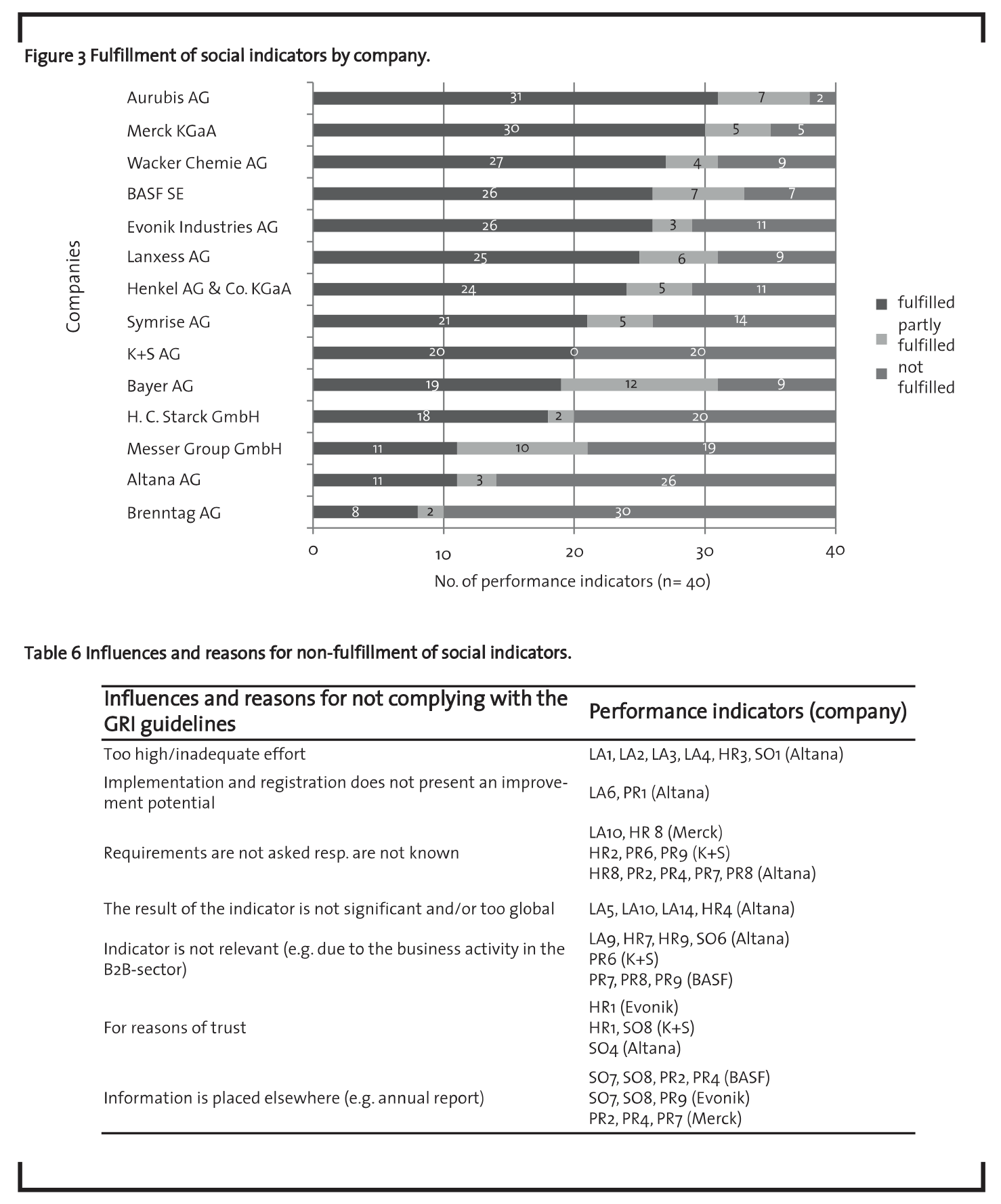

Figure 3 shows the fulfillment of 40 social performance indicators by company. There is a difference between a total, partial and non-fulfillment. As can be seen, results range from 31 fulfilled and 2 unfulfilled indicators for Aurubis to Brenntag with only 8 fulfilled and 30 unfulfilled performance indicators. It is obvious that there are major differences in the scope of addressed fields. Companies fulfilling more indicators give a deeper insight into their social responsibility management and can be seen as a positive example in relation to other companies. However, the scope does not always directly reflect the status of social responsibility management within a company.

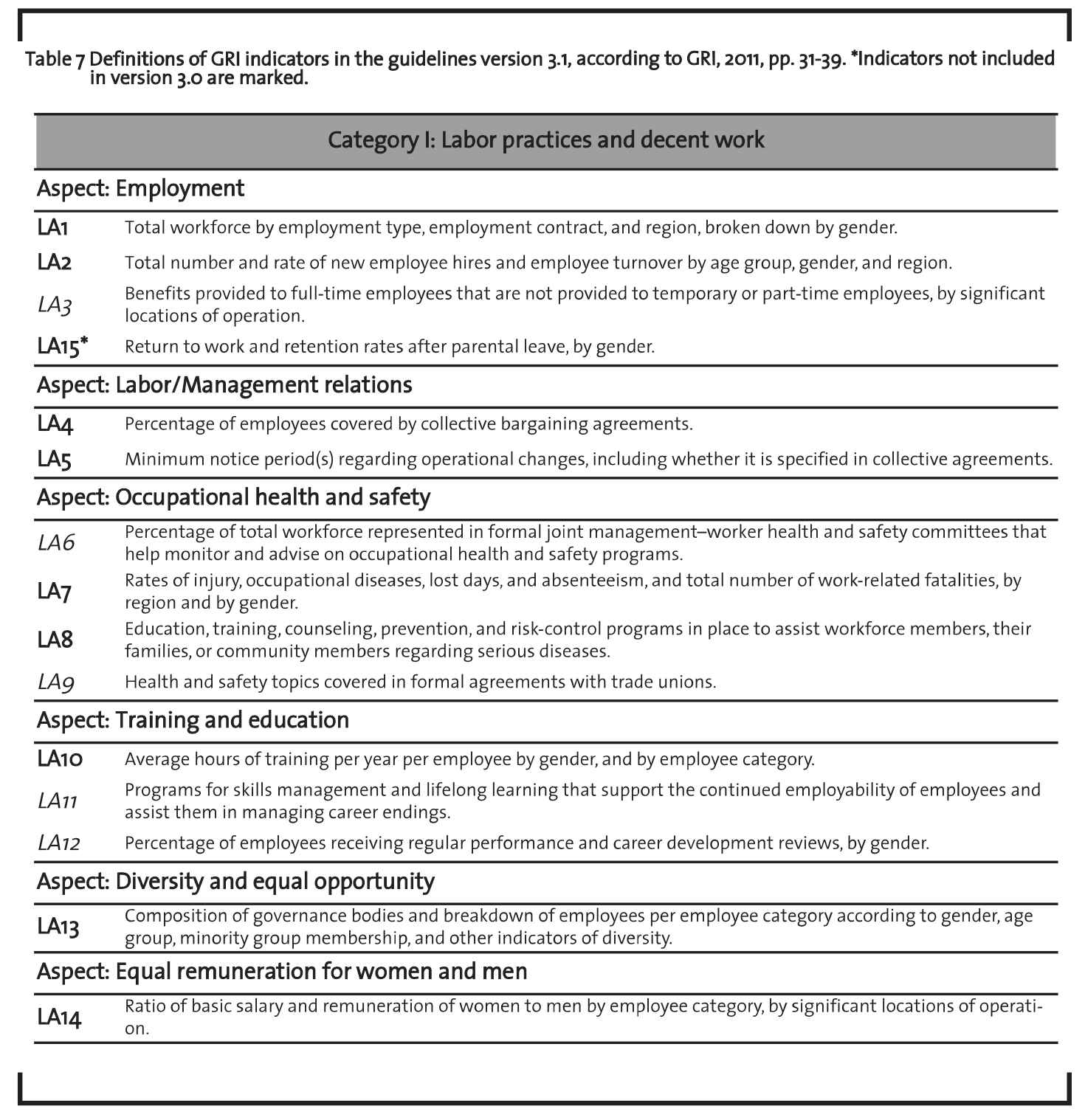

Reasons for not fulfilling or rather not reporting individual social indicators are only rarely stated in the CSR reports. In the majority of cases, the non-fulfilled indicators are not listed in the GRI index at all. Justifications for non-fulfillment can only be found in the reports of Altana, BASF, Evonik, K+S and Merck and are summarized in table 6. Repeatedly stated reasons for non-fulfillment are a high effort for the acquisition of appropriate data or lacking relevance for the own company. Some social indicators are also published in other documents such as annual reports. The only reason mentioned for fulfilling indicators is that there are no incidents within the company and therefore the indicator is fulfilled. These statements are utilized by Aurubis, Lanxess and Merck.

4 Discussing implications and concluding remarks

The analysis of CSR reports by German chemical companies has shown that the social dimension is seen as an essential part of sustainable development in terms of their strategies and goals. The reporting of social aspects is preferably based on the GRI guidelines. Still, many other guidelines are referred to as well when preparing reports. However, the results indicate a high discrepancy in social sustainability reporting relating to the scope and focus of social topics or performance.

4.1 Which social sustainability issues are most relevant for companies and why?

Although not all companies analyzed have clearly stated their sustainability issues or objectives in their reports, some social elements seem to have a higher priority and are reported more often. Occupational health and safety as well as social commitment are most frequently listed, and play therefore a central role in social sustainability management. The goals of CSR measures named in the reports are consistent with the frequency of appearing topics in CSR reports as companies primarily intend to reduce work accidents and to support (local) social projects. These CSR activities can help companies to gain decisive competitive advantages, as both, the internal and external corporate level are addressed. Overall, the abovementioned aspects aim to enhance the company’s attractiveness and thereby facilitate recruiting new employees and protecting existing human capital. Particularly in the chemical industry, ensuring safety is of high importance due to handling hazardous materials and operating highly complex technological systems.

Further, the education and training of employees as well as fostering diversity and equal opportunities are frequently presented as social sustainability goals. This shows that motives of social actions aim to increase the working atmosphere and employee satisfaction in order to strengthen its own competitive position. In addition, social commitment generates trust and credibility. Social sustainability measures allow companies to counteract the unpleasant image of chemical companies in the public and to cooperate with their environment. Still, the activities within the sample are mainly directed towards employees and therefore have an internal character.

4.2 How do social sustainability reports differ and what influence results on stakeholder benefits?

GRI indicators are divided into four categories in order to give companies a structural guideline to measure and report social aspects. The analysis of the reports shows that the degree of fulfillment between individual performance indicators differs strongly (see figure 3). Even within the narrow sample of German chemical companies, large differences between reported indicators can be observed. Furthermore, there is no single indicator which is fulfilled by all of the companies.

It is striking that the category of product responsibility is overall the field with the fewest fulfilled indicators. With regard to the industrial sector, this empirical evidence seems rather unexpected since many chemical products or their production processes provide a rather high risk potential. However, due to the different interpretation by companies, it is not identifiable if the reporting of indicators should be assessed positively or negatively. For example the content of unfulfilled GRI indicators in the product sector partly includes incidents of disrespect regarding the product safety. On the one hand, not reporting those indicators could imply that the company has not recorded any incidents or on the other hand, that it does not want to report about incidents. Furthermore, a fulfillment of these indicators does not automatically mean that negative incidents within the company are present as fulfilling an indicator occurs by giving a positive or negative feedback. Therefore, an assessment and adequate comparability cannot solely be based on the GRI Index. Especially for stakeholders, the comparison of social sustainability activities will be affected if the company has not reported any reasons for non-fulfilled indicators. The transparency and accountability of social sustainability reports is thus limited. Companies should enhance the credibility of reporting by also declaring their weaknesses or shortcomings concerning the social indicators. A mere listing of reported guidelines and initiatives provide stakeholders just a rough view of the orientation of policies, but state little about whether and how they are implemented within the company. This is also referred to as bluewashing (Voegtlin and Pless, 2014).

In summary, the benefits achieved through reporting on the social dimension of sustainability are mostly non-monetary, at least in the shortterm. Transparent and detailed reports can lead to improved reputation of the company among stakeholders. These advantages enable companies to expand and secure their social and human capital and provide an enhanced competitive position, for example in the field of employer attractiveness. However, a reliable analysis and comparability of CSR reports is hardly possible as reported guidelines and indicators as well as the content of the CSR reports presented by companies differ widely.

It can be concluded that social sustainability reports could create more transparency and present a good tool for communication towards stakeholders in general. However, until reliable guidelines which are more straightforward and clear in their content emerge, the usability of these reports for companies, stakeholders, experts and inter-company comparison is rather limited. The next step is already introduced by the GRI’s G4 guidelines which further structure and improve the existing guideline. It will be highly interesting to see to which extent future CSR reports will adopt this guideline and if it is capable to increase comparability of social sustainability reporting.

References

Beddoe, R., Costanza, R., Farley, J., Garza, E., Kent, J., Kubiszewski, I., Martinez, L., McCowen, T., Murphy, K., Myers, N., Ogden, Z., Stapleton, K., Woodward, J. (2009): Overcoming systemic road-blocks to sustainability: the evolutionary redesign of worldviews, institutions, and technologies, Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(8), pp. 2483-2489.

Bostrom, M. (2012): A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: introduction to the special issue, Sustainability: Science, Practice, & Policy, 8 (1), pp. 3-14.

Campbell, J.L. (2006): Institutional analysis and the paradox of corporate social responsibility, American Behavioral Scientist, 49 (7), pp. 925-938.

CEFIC (2014): Social Responsibility in the European chemical industry, available at http://www.cefic.org/Documents/Learn%20and%20Share/Social-Responsability-Brochure/Social-Responsability-in-the-european-chemical-Industry.pdf, accessed on 01. September 2015.

Clausen, J., Loew, T. (2009): CSR und Innovation: Literaturstudie und Befragung, available at www.4sustainability.org, accessed on 01 September 2015.

Commission of the European Communities (2001): Green Paper – Promoting a European framework for Corporate Social Responsibility (DOC/01/9), Brussels.

Deutscher Bundestag (1997): Konzept Nachhaltigkeit. Fundamente fur die Gesellschaft von morgen, Zwischenbericht der Enquete-Kommission „Schutz des Menschen und der Umwelt – Ziele und Rahmenbedingungen einer nachhaltig zukunftsvertraglichen Entwicklung“, Deutscher Bundestag, Berlin.

Dyllick, T. (2003): Konzeptionelle Grundlagen unternehmerischer Nachhaltigkeit, Handbuch Nachhaltige Entwicklung, Springer, pp. 235-243.

Dyllick, T., Hockerts, K. (2002): Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability, Business strategy and the environment, 11 (2), pp. 130-141.

Elkington, J. (1997): Cannibals with forks, The triple bottom line of 21st century, Capstone Publishing Ltd., Oxford.

Epstein, M.J., Roy, M.-J. (2003): Making the business case for sustainability, Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 2003 (9), pp. 79-96.

Figge, F., Hahn, T., Schaltegger, S. ,Wagner, M. (2002): The sustainability balanced scorecard–linking sustainability management to business strategy, Business Strategy and the Environment, 11 (5), pp. 269-284.

Foerstl, K., Reuter, C., Hartmann, E., Blome, C. (2010): Managing supplier sustainability risks in a dynamically changing environment—Sustainable supplier management in the chemical industry, Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 16 (2), pp. 118-130.

Freeman, R. E., Velamuri, S. R. (2008): A new approach to CSR: Company stakeholder responsibility, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1186223 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1186223, accessed on 01 September 2015.

Freeman, R. E. (1984): Strategic management a stakeholder approach, Pitman series in business and public policy, Pitman publishing Inc., Boston, MA.

Gladwin, T.N., Kennelly, J.J., Krause, T.-S. (1995): Shifting paradigms for sustainable development: Implications for management theory and research, Academy of Management Review, 20 (4), pp. 874-907.

Goodland, R. (2002): Sustainability: Human, social, economic and environmental , available at http://www.balticuniv.uu.se/index.php/component/docman/doc_download/435-sustainability-human-social-economic-and-environmental. pdf, accessed on 1 September 2015.

GRI (2015): Sustainability disclosure database, available at http://database.globalreporting.org/ search, accessed on 30. January 2015.

GRI (2014): Ready to Report – SME booklet, available at https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/Ready-to-Report-SME-booklet-online.pdf, accessed on 01 September 2015.

GRI (2013): Global Reporting Initiative – G4 Leitlinien zur Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung, available at https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/German-G4-Part-One.pdf, accessed on 01 September 2015.

GRI (2011): Global Reporting Initiative – Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, available at https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/G3.1-Guidelines-Incl-Technical-Protocol.pdf, accessed on 01 September 2015.

Haasis, H.-D. (2008): Produktions- und Logistikmanagement, Gabler Verlag, Wiesbaden.

Hart, S.L. (1997): Beyond greening: strategies for a sustainable world, Harvard Business Review, 75 (1), pp. 66-77.

Hauth, P., Raupach, M. (2001): Nachhaltigkeitsberichte schaffen Vertrauen, Harvard Business Manager, 23 (5), pp. 24-33.

Heins, B. (1998): Soziale Nachhaltigkeit, Analytica, Berlin.

Hentze, J., Thies, B. (2014): Stakeholder-Management und Nachhaltigkeits-Reporting, Springer-Verlag, Wiesbaden.

Hoffman, A.J. (1999): Institutional evolution and change: Environmentalism and the US chemical industry, Academy of Management Journal, 42 (4), p. 351-371.

ICCA (2006): Global Product Strategy, available at http://www.icca-chem.org/en/home/globalproduct-strategy/, accessed on 01 September 2015.

ICCA (2010): Responsible Care Global Charter, available at http://www.cefic.org/Documents/ResponsibleCare/RC-global-charter.pdf, accessed on 01 September 2015.

ILO (2009): International Labour Organization Declarations, available at http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/lang–en/index.htm, accessed on 01 September 2015.

ISO (2011): ISO 26000:2010 – Social responsibility, available at http://www.iso.org/iso/home/standards/iso26000.htm, accessed on 01 September 2015.

Jahn, G.A., Sachsische Hans-Carl-von-Carlowitz-Gesellschaft (ed.) (2013): Die Erfindung der Nachhaltigkeit – Leben, Werk und Wirkung des Hans Carl von Carlowitz, oekom-Verlag, Munchen.

Jörissen, J., Kopfmüller, J., Brandl, V., Paetau, M. (1999): Ein integratives Konzept nachhaltiger Entwicklung, Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe.

Lamberti, L., Lettieri, E. (2009): CSR practices and corporate strategy: Evidence from a longitudinal case study, Journal of Business Ethics, 87 (2), pp. 153-168.

Loew, T., Braun, S. (2009): CSR-Handlungsfelder-Die Vielfalt verstehen, Ein Vergleich der Handlungsfelder aus den Perspektiven Unternehmen, Politik, GRI und ISO 26000, available at http://www.4sustainability.de/fileadmin/redakteur/ Publikationen/Loew-Braun2009_CSRHandlungsfelder-im-Vergleich.pdf, accessed on 02 September 2015.

Loew, T., Rohde, F. (2013): CSR und Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement, available at: http://www.4sustainability.de/fileadmin/redakteur/bilder/Publikationen/Loew_Rohde_2013_CSR-und-Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement.pdf, accessed on 02 September 2015.

McWilliams, A. (2015): Corporate Social Responsibility, in: Wiley Encyclopedia of Management, 12, pp. 1-4.

McWilliams, A., Siegel, D. (2001): Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective, Academy of Management Review, 26(1), pp. 117-127.

McWilliams, A., Siegel, D.S., Wright, P.M. (2006): Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications, Journal of Management Studies, 43 (1), pp. 1-18.

OECD (2015): Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) Principles, available at http://www.oecd.org/about/, accessed on 01 September 2015.

OHS Group (2007): Occupational Health and Safety Assessment System (OHSAS) 18001, available at http://www.ohsas-18001-occupational-health-and-safety.com/what.htm, accessed on 01 September 2015.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F.L., Rynes, S.L. (2003): Corporate social and financial performance: A metaanalysis, Organization Studies, 24 (3), pp. 403-441.

Perrini, F., Tencati, A. (2006): Sustainability and stakeholder management: the need for new corporate performance evaluation and reporting systems, Business Strategy and the Environment, 15 (5), pp. 296-308.

Porter, M.E., Kramer, M.R. (2006): The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility, Harvard Business Review, 84 (12), p. 78-92.

Potts, J., Lynch, M., Wilkings, A., Huppe, G., Cunningham, M., Voora, V. (2014): The State of Sustainability Initiatives Review 2014: Standards and the Green Economy, available at https://www.fastinternational.org/files/The%20 State%20of%20Sustainability%20Initiatives%20Review%202014.pdf, accessed on 01 September 2015.

RNE (2014): Leitfaden zum Deutschen Nachhaltigkeitskodex, available at https://www.bertelsmann-stif-tung.de/fileadmin/files/Projekte/31_Nachhaltigkeitsstrategien/Leitfaden_zum_Deutschen_Nachhaltigkeitskodex.pdf, accessed on 01 September 2015.

Robertson, D.C., Nicholson, N. (1996): Expressions of corporate social responsibility in UK firms, Journal of Business Ethics, 15 (10), pp. 1095-1106.

SAI (2014): Social Accountability 8000 – International Standard, available at http://saintl.org/_data/n_0001/resources/live/SA8000% 20Standard%202014.pdf, accessed on 01 September 2015.

Salzmann, O., Ionescu-Somers, A., Steger, U. (2005): The business case for corporate sustainability: literature review and research options, European Management Journal, 23 (1), pp. 27-36.

Schaltegger, S., Hasenmuller, P. (2005): Nachhaltiges Wirtschaften aus Sicht des” Business Case of Sustainability”, Ergebnispapier zum Fachdialog des Bundesumweltministeriums, Centre for Sustainability Management, Luneburg.

Schaltegger, S., Herzig, C., Kleiber, O., Klinke, T., Muller, J., Deutschland Bundesministerium fur Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit (ed.), Ecosense (ed.), Centre for Sustainability Management (ed.) (2007): Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement in Unternehmen, available at http://www.econsense.de/sites/all/files/nachhaltigkeitsmanagement_unternehmen.pdf, accessed on 01 September 2015.

Spangenberg, J.H., Bonniot, O. (1998): Sustainability indicators: a compass on the road towards sustainability, available at http://www.ulb.ac.be/ceese/STAFF/Tom/spangenberg.pdf, accessed on 02 September 2015.

UN 2015: The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact, available at https://www.unglobalcompact. org/what-is-gc/mission/principles, accessed on 01 September 2015.

UN (2013): Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS), 5th revised ed., available at http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trans/danger/publi/ghs/ghs_rev05/English/ST-SG-AC10-30-Rev5e.pdf, accessed on 01 September 2015.

UNGA (1987): Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future, available at www.un-documents.net/ourcommon-future.pdf, accessed on 02 September 2015.

Vallance, S., Perkins, H.C., Dixon, J.E. (2011): What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts, Geoforum, 42 (3), p. 342-348.

VCI (2013): Chemiehoch3 – Sustainability Guidelines for the Chemical Industry in Germany, available at https://portal.vci.de/Downloads/Publikation/Sustainability-Guidelines-German-Chemical-Industry-Chemie3.pdf, accessed on 02 September 2015.

Voegtlin, C., Pless, N. M. (2014): Global governance: CSR and the role of the UN Global Compact, Journal of Business Ethics, 122 (2), pp. 179-191.

Wagner, B., Henle, B. (2008): Die bruchige Saule der Nachhaltigkeit, Okologisches Wirtschaften-Fachzeitschrift, 23 (2), pp. 30-34.

Wahba, H. (2008): Exploring the moderating effect of financial performance on the relationship between corporate environmental responsibility and institutional investors: Some Egyptian evidence, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15 (6), pp. 361-371.

Weber, M. (2008): The business case for corporate social responsibility: A company-level measurement approach for CSR, European Management Journal, 26 (4),pp. 247-261.

Appendix