Supporting start-ups in the process industries with accelerator programs: Types, design elements and success measurement

Abstract

Accelerators support the fast-track development of start-ups. Although their emergence and popularity has increased during the last years, limited research exists on accelerator types and whether the organizational context (e.g. nature of business, industry) influences their five design elements: 1) funding structure and governance, 2) strategic goals and focus, 3) selection process, 4) program package, and 5) alumni relations. For the identification of accelerator types in the context of the process industries, ten interviews with accelerator managers were conducted. Three different accelerator types were found: 1) Corporate accelerator, 2) Public accelerator, and 3) Hybrid accelerator. This study provides an overview of each accelerator type and their respective design elements. In addition, for each accelerator type, success factors, key challenges, and success measurements are presented. The results of this study will help those, who fund, setup, manage and operate accelerators in the process industries to design their program appropriately in order to attract, select, and fully exploit the economic potential of participating start-ups.

1 Introduction

A wide range of support forms for nascent ventures like start-ups exist such as incubators, venture studios, start-up competitions or business angel investors (Cohen et al., 2019). One of these support forms is an accelerator program, which is also called seed accelerator, start-up accelerator or business accelerator (hereafter we refer to them merely as accelerators) (Cohen et al. 2019). Accelerators are a relatively novel phenomenon to foster entrepreneurship, but their emergence and popularity has increased during the last years since the foundation of the Y Combinator program in 2005 and provide new research opportunities (Battistella et al., 2017; Cohen et al., 2019; Drover et al., 2017; Hallen et al., 2020; Y Combinator, 2020). Since 2005, Y Combinator has funded over 2,000 start-ups and these companies (e.g. Dropbox, Airbnb, stripe) have reached a combined valuation over 100 billion US$ (Y Combinator, 2020).

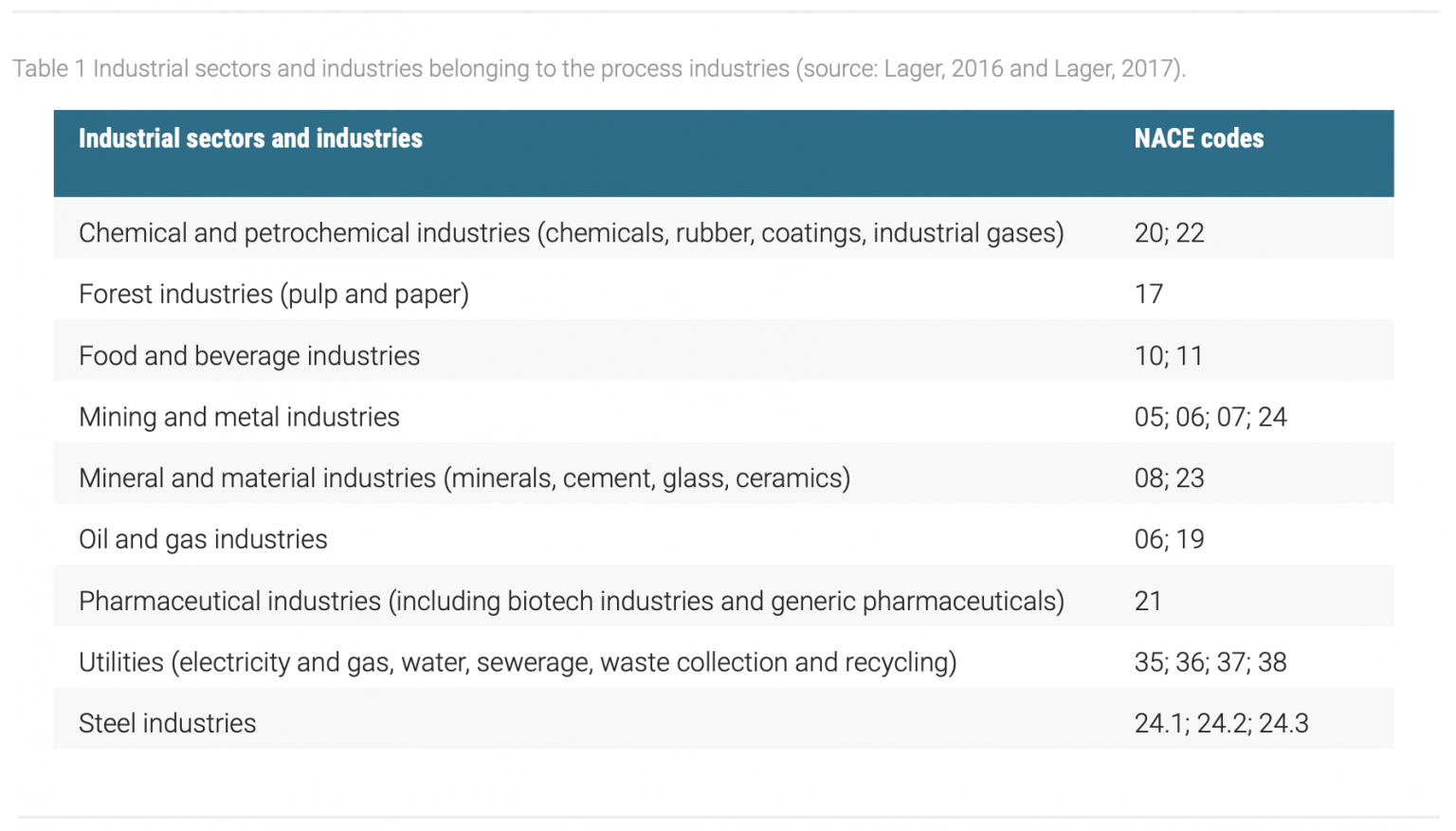

Therefore, accelerators represent a rapidly growing format to “accelerate” the development of start-ups (Cohen et al., 2019; Wright and Drori, 2018). Existing literature gives an overview about the current state of research regarding the definition of accelerators and their design (Cohen et al., 2019; Pauwels et al. 2016). However, research on this new organizational form is still evolving (Cohen et al., 2019). While taking a closer look at accelerators, differences in their types and strategic goals can be observed resulting in different designs (Kohler, 2016; Moschner et al. 2019; Prexel et al., 2019; Shankar and Shepherd, 2019). Shankar and Shepherd (2019) posed the research question whether the organizational context (e.g. nature of business, industry) matters for how an accelerator is designed and run. Thus, it becomes increasingly important to investigate which accelerator types are used in different industries, and which accelerator types and designs are most suitable for certain industries and businesses (Shankar and Shepherd, 2019). In general, most research on accelerators has focused on start-ups dealing with digital media and relating to the IT industry (Crișan et al., 2019; Malek et al., 2014). For this reason, little is known about accelerator types, which support start-ups in other areas such as advanced materials, biotechnology, and clean energy (Malek et al., 2014). For example, Malek et al. (2014) investigated a typology of accelerator capabilities that are relevant for the development and commercialization of start-ups in the clean technology industry. In doing so, they helped researchers and practitioners to enhance their understanding of how capabilities of accelerators can vary to meet different goals (Malek et al., 2014). In addition, Malek et al. (2014) showed with their research and focus on a specific industry how accelerator managers can align their program to the needs of the respective industry and the corresponding characteristics of start-ups in this area. Currently, no research on accelerator types and their design in the context of the process industries exists. The process industries cover multiple industrial sectors, which also compose a substantial part of the entire manufacturing industry including petrochemicals and chemicals, food and beverages, mining and metals, mineral and materials, (bio)pharmaceuticals, pulp and paper, and steel and utilities (Lager, 2017; Lager et al., 2013). Table 1 lists the industrial sectors and industries with their associated NACE codes that belong to the cluster of the process industries in alphabetical order according to Lager (2016) and Lager (2017).

Lager et al. (2013) characterize the process industries as rather conservative with predominately long, complex, and rigid supply and value chains. In the process industries, companies are often very asset-intensive and highly integrated in one or a few physical locations which reduces their ability to respond quickly to changes in the short-term (Lager et al., 2013). Further, Lager et al. (2013) highlight that research and development (R&D) and innovation in the process industries play a crucial role for future success.

Accelerators could help to rejuvenate process industries by stimulating entrepreneurship while combining and integrating resources from an innovation ecosystem with start-ups and their entrepreneurial teams (Cohen et al., 2019). For instance, Berger et al. (2019) emphasize the relevance of start-ups for the chemical industry in a current study, which they conducted for the German chemical industry association (Verband der Chemischen Industrie e.V.). In their study, Berger et al. (2019, p.2) define chemical start-ups as “young firms that offer goods and services based on chemical knowledge and chemical technologies”. Berger et al. (2019) mention that start-ups can generate innovative ideas, stimulate competition, develop new applications and technologies (in particular if low demand is not sufficiently attractive for established and large companies to engage in new areas), transfer research results into commercial products, or compensate losses while creating new jobs in the chemical industry. Moreover, Berger et al. (2019) found that chemical start-ups often aim at new business areas and models outside of traditional chemistry and offer specialized services like R&D services to third parties (34%), produce chemical goods (19%), or provide IT services relating to chemistry (13%), while another third is still in the R&D phase (34%). However, in the process industries such as the chemical industry, start-ups face various challenges and rarely achieve market breakthroughs because of their resource constraints (van Gils and Rutjes, 2017). In addition, they do not possess manufacturing equipment or distribution channels that established companies have, or must overcome the liability of newness (van Gils and Rutjes, 2017; Yin and Luo, 2018). Thus, accelerators could play a crucial role in supporting start-ups to overcome these challenges to create novel and valuable solutions, which could enhance R&D and innovation, while contributing to future success of the process industries. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to provide an overview of accelerator types and their design elements, which have emerged in the context of the process industries. For each accelerator type, success factors, key challenges and success measurements are also presented. The results of this study will help those, who fund, setup, manage, and operate accelerators in the process industries to design their program appropriately in order to attract, select, and fully exploit the economic potential of participating start-ups.

This study is structured as follows. The second chapter explains the theoretical background of accelerators and presents the research questions. Then, the third chapter describes the method and research design, followed by the fourth chapter presenting the findings of our study and discussing them. Finally, the last chapter provides theoretical and managerial implications, while also giving an outlook for further research.

2 Accelerators

In general, accelerators aim at rapid acquisition or even failure of start-ups by exposing them quickly to the market to test their solution, while using minimal resources (Stayton and Mangematin, 2019). Cohen et al. (2019, p. 1782) define an accelerator as ”a fixed-term, cohort-based program for startups, including mentorship and/or educational components, that culminates in a graduation event”, while Pauwels et al. (2016, p.15) introduced a definition based on six characteristics including “(1) Possible offer of upfront investment (£10k–£50k), often in exchange for equity (~5–10%); (2) Time-limited support, comprising programmed events and intensive mentoring; (3) An application process that is “in principle” open to all, yet highly competitive; (4) Cohorts or classes of start-ups rather than individual companies; (5) Mostly a focus on small teams, not individual founders; (6) Periodic graduation with a Demo Day/Investor Day”.

Subsequently, the design elements of an accelerator are presented.

2.1 Design elements

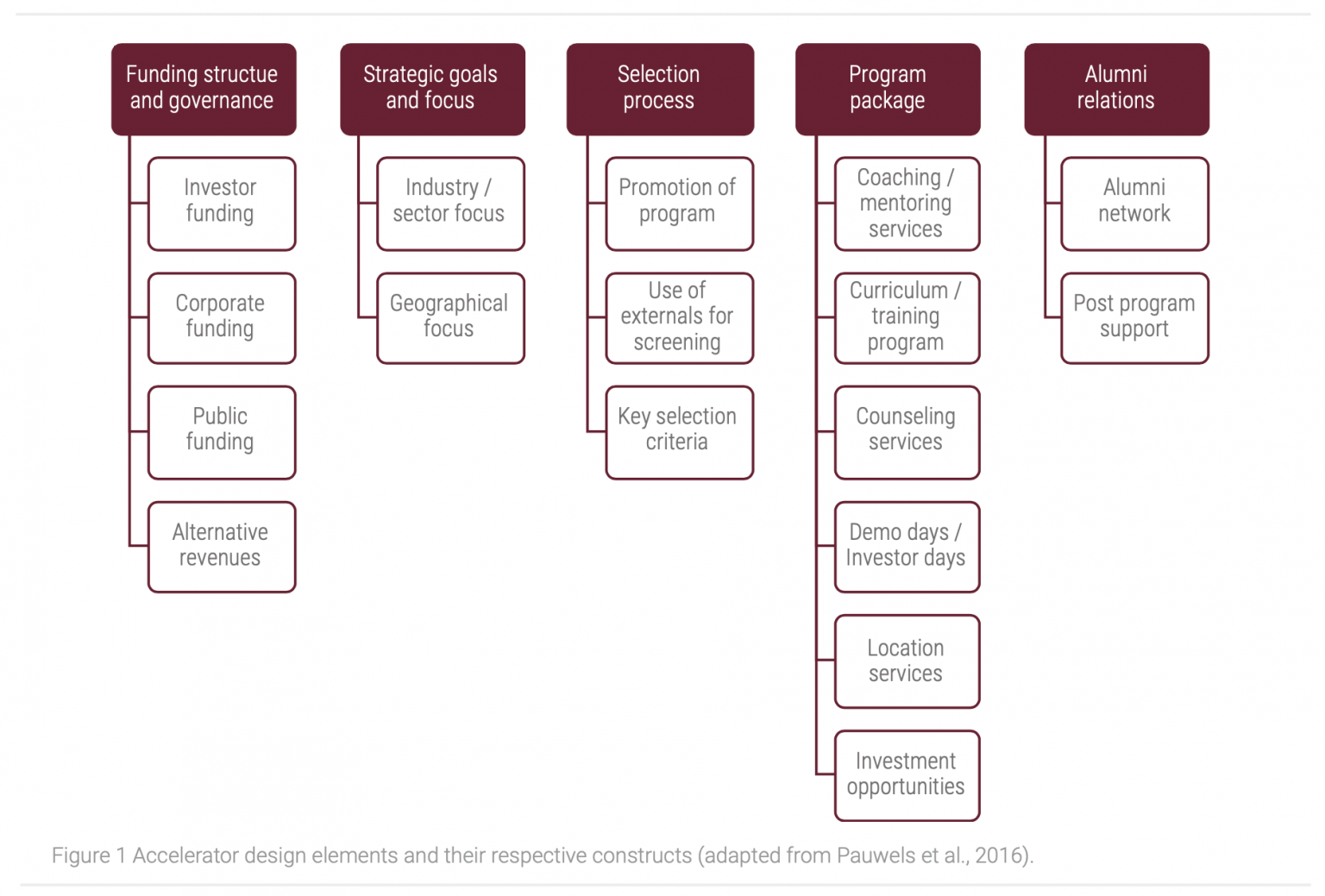

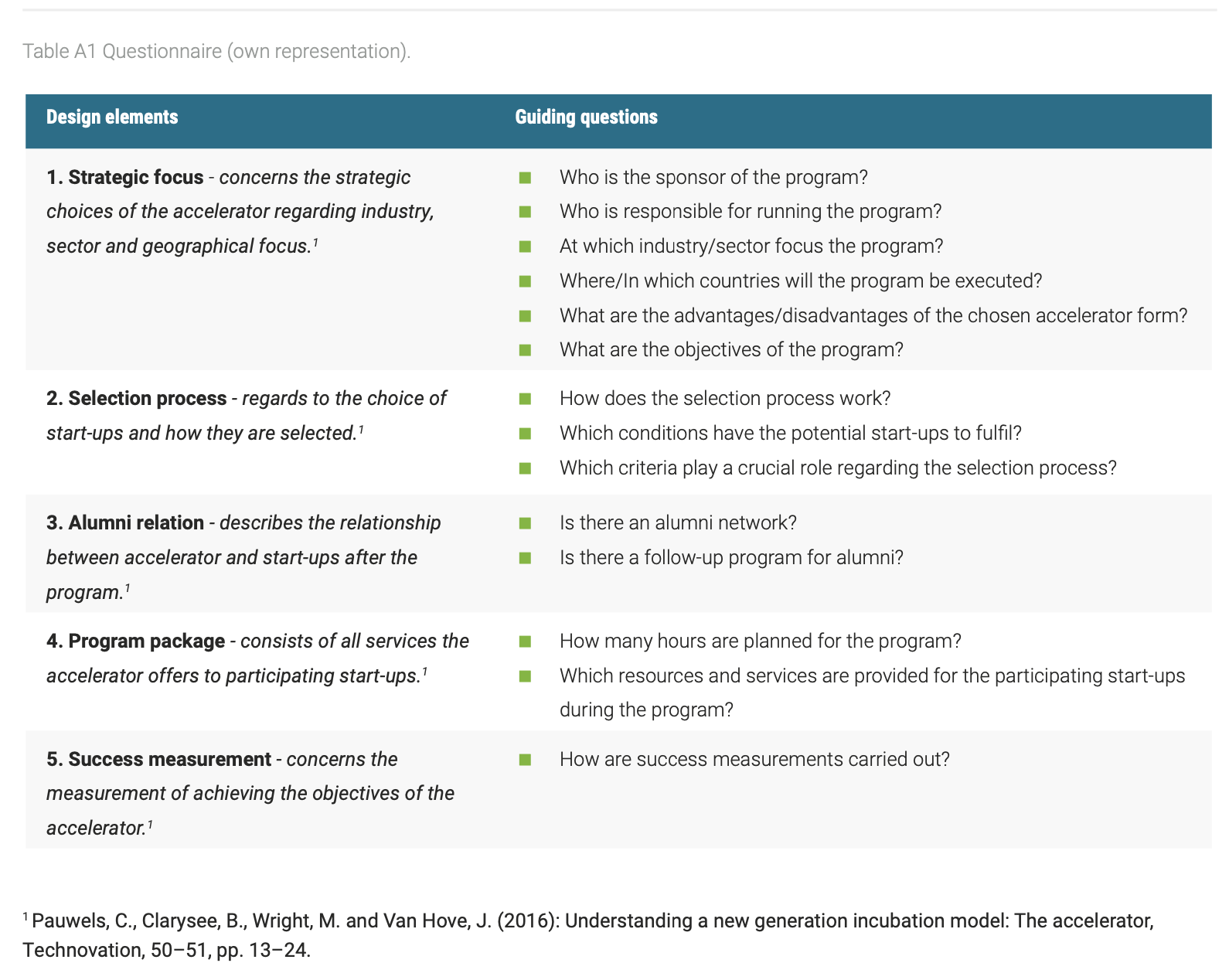

Pauwels et al. (2016) conducted a repertory grid construction and cross-case analysis with 13 accelerator cases and found five common accelerator design elements among them: 1) Funding structure, 2) Strategic focus, 3) Selection process, 4) Program package, and 5) Alumni relations. For the five design elements, they identified 17 constructs. Figure 1 contains all design elements and the respective constructs based on Pauwels et al. (2016). Some design elements and constructs were adapted or renamed in Figure 1 based on other existing literature and due to the research questions of this study. Subsequently, the five design elements of Pauwels et al. (2016) and their extensions will be presented since they build the theoretical foundation of this research.

2.1.1 Funding structure and governance

The first design element concerns the funding structure and governance of the accelerator. Vandeweghe and Fu (2018) highlight that accelerators manage relationships with internal and external stakeholders, which affect the achievement of the program’s goals. Internal stakeholders are sponsors, directors and staff/team, whereas external stakeholders are partners, investors and portfolio start-ups (Vandeweghe and Fu, 2018).

Sponsors fund the accelerator. Cohen et al. (2019, p. 1788) define program sponsors as “external institutions that provide financial or in-kind support, including office space, professional services, mentors, and endorsement, to accelerator programs”. Pauwels et al. (2016) propose four possible funding sponsors: private investors, corporations (hereafter we refer to them merely as corporates), public authorities, or alternative revenues. Alternative revenues may originate from investments in supported start-ups or through the organization of events and workshops (Pauwels et al., 2016). Malek et al. (2014) argue that the funding structure and operations of an accelerator are inter-related, since the available financial resources determine the opportunities in supporting start-ups, or to which extent they will fund and take equity of new ventures.

Concerning the governance of an accelerator, directors or managers are responsible for the strategy of the program, while the accelerator’s staff/team execute the operational day-to-day activities (Vandeweghe and Fu, 2018). In this study, organizational governance refers to the operational model of the accelerator and how it is run (e.g. by an internal team/department or operations are outsourced to an external service provider). Therefore, organizational governance was added to the design element funding structure, since the entity or organization that is responsible for running the program may not belong to the sponsor organization of the accelerator.

2.1.2 Strategic goals and focus

The design element strategic goals and focus describes the strategic choices of accelerators concerning their industry/sector and geographical focus (Pauwels et al., 2016). The industry/sector focus can vary from very generic (no vertical focus at all) to very specific (focus on a specific industry/sector/technology) (Pauwels et al., 2016). Additionally, accelerators can choose between being locally versus internationally active which refers to the geographical focus (Pauwels et al., 2016). Leatherbee and Gonzalez-Uribe (2018a) emphasize the close relation between the funding of accelerators and their corresponding goals and focus. Therefore, strategic goals were added to the design element strategic focus in Figure 1. Finally, Pauwels et al. (2016) highlight that the goals of the accelerator’s key stakeholders, which fund or support the accelerator, are the main driver for the orchestration of an accelerator’s activities.

2.1.3 Selection process

The design element selection process refers to the accelerator’s choice of start-ups for the next cohort (Pauwels et al., 2016). Pauwels et al. (2016) found that accelerators use a rigorous, multi stage selection process to attract and identify suitable start-ups for the program, which will be subsequently described. Usually, the application form is online on a software platform and may include a brief pitch deck and video. For the selection of suitable start-ups, all applications are screened and shortlisted by the accelerator team, usually with the involvement and use of externals. Pre-selected start-ups are invited to a pitch day at which they present their ideas and solutions to a selection committee that consists of members from the accelerator team and relevant externals like mentors, investors or alumni. The pitch day represents the final-selection stage. After the end of the pitch day, the selection committee chooses the final start-ups, which will form the next cohort of the accelerator (Leatherbee and Gonzalez-Uribe, 2018b).

Pauwels et al. (2016) found that the main selection criterion was the team. In contrast, Leatherbee and Gonzalez-Uribe (2018b) showed that selection criteria can differ among different accelerator types. Thus, team may not only be the primary selection criterion of accelerators in the context of the process industries and the construct team was renamed into key selection criteria in Figure 1.

2.1.4 Program package

The design element program package concerns all service offers of an accelerator (Pauwels et al., 2016). Mentoring services are a central pillar of an accelerator (Pauwels et al., 2016). In Figure 1, Coaching was added to the construct Mentoring services of Pauwels et al. (2016), since no explicit distinction in literature exists concerning the definition and roles of both functions (Crişan et al., 2019; Roberts and Lall, 2019). Both, mentors and coaches fulfill equal or similar roles while providing assistance to start-ups in the accelerator (Crişan et al., 2019; Roberts and Lall, 2019). For instance, coaches and mentors help start-ups to define and validate their business model, or to connect with customers and investors. Usually, an accelerator has a structured curriculum or training program, which covers a wide range of topics among finance, marketing, management and others like pitching that are often taught in expert workshops or lectures (Pauwels et al., 2016). Furthermore, accelerators offer counselling services on a regular basis, e.g. in form of weekly “office hours”, in which start-ups can ask for support, or their progress is assessed and monitored (Pauwels et al., 2016). Demo and investor days provide the opportunity for participating start-ups to network and to present their solution to potential customers and investors (Cohen et al., 2019; Pauwels et al., 2016). Location services refer to the offer of co-working spaces to enhance collaboration and peer learning among participants (Pauwels et al., 2016). Finally, start-ups normally receive a small amount of funding in exchange for equity (investment opportunity) ranging from 3-10% according to Pauwels et al. (2016). In general, the program has a duration of three to six months (Bliemel et al., 2019), but can also last between four weeks and one year (Cohen et al., 2019).

2.1.5 Alumni relations

The last design element alumni relations covers the interaction of the accelerator with alumni after the end of the program (e.g. through regular events) (Pauwels et al., 2016). Pauwels et al. (2016) highlight the value of successful alumni as potential mentors and references for success stories which also increase the reputation of the accelerator.

2.2 Types

Cohen et al. (2019) mention that most existing research has considered accelerators as largely homogenous in their business model and does not take into account that accelerators vary strongly in their design. They revealed that the design of accelerators may vary because of a strong correlation between the type of funding sponsor (e.g. corporate, investor, academia, foundation, or government) and the background of founding managing directors (e.g. prior investor, entrepreneur, corporate, university, or government experience). Founders of the accelerator may design their program differently according to their objectives (Cohen et al., 2019). This influences and causes differences in the performance of participating start-ups (Cohen et al., 2019).

Pauwels et al. (2016) found that accelerators varied in their architecture according to their approach to each of the design elements. In total, Pauwels et al. (2016) identified three different accelerator types with an own design theme: 1) ecosystem builder, 2) deal-flow maker, and 3) welfare stimulator. The ecosystem builder aims at matching customers with start-ups and to build-up a corporate ecosystem. The deal-flow maker has the goal of identifying investment opportunities for investors and is comparable to a venture capital program. The welfare stimulator pursues the goal of stimulating start-up activity and economic growth, and is typically financed by local, national or international funding schemes. Pauwels et al. (2016) argue that the design theme determines how an accelerator orchestrates and connects the different design elements.

For the identification of different accelerator types and the further classification of each type into sub-types, researchers can use the identified design elements of Pauwels et al. (2016). In doing so, it is possible to investigate similarities and differences between accelerators by taking a design lens approach as an appropriate theoretical framework (Pauwels et al., 2016). For instance, Prexel et al. (2019) looked at differences and similarities among corporate accelerators exhibiting the ecosystem builder theme of Pauwels et al. (2016) and classified their results into five ecosystem builder accelerator sub-types: 1) Start-up accelerator, 2) Idea-lab accelerator, 3) Intrapreneurship accelerator, 4) Venture-client accelerator, and 5) White-label accelerator. Furthermore, Moschner et al. (2019) identified four different corporate accelerator types: 1) In-house accelerator, 2) Hybrid accelerator, 3) Powered by accelerator, and 4) Consortium accelerator. Moreover, Kanbach and Stubner (2016) also found four corporate accelerator types: 1) Listening Post, 2) Value Chain investor, 3) Test laboratory, and 4) Unicorn hunter.

Shankar and Shepherd (2019) proposed to investigate whether the organizational context (e.g. nature of business, industry) matters for how an accelerator is designed and run, thus revealing which accelerator types are used in different industries and which accelerator types and designs are most suitable for certain industries and businesses. Currently, existing literature mainly provides an overview of different corporate accelerator types, and hence research on other accelerator types and their design is missing. Therefore, this study addresses this research gap while taking into account the organizational context of the process industries.

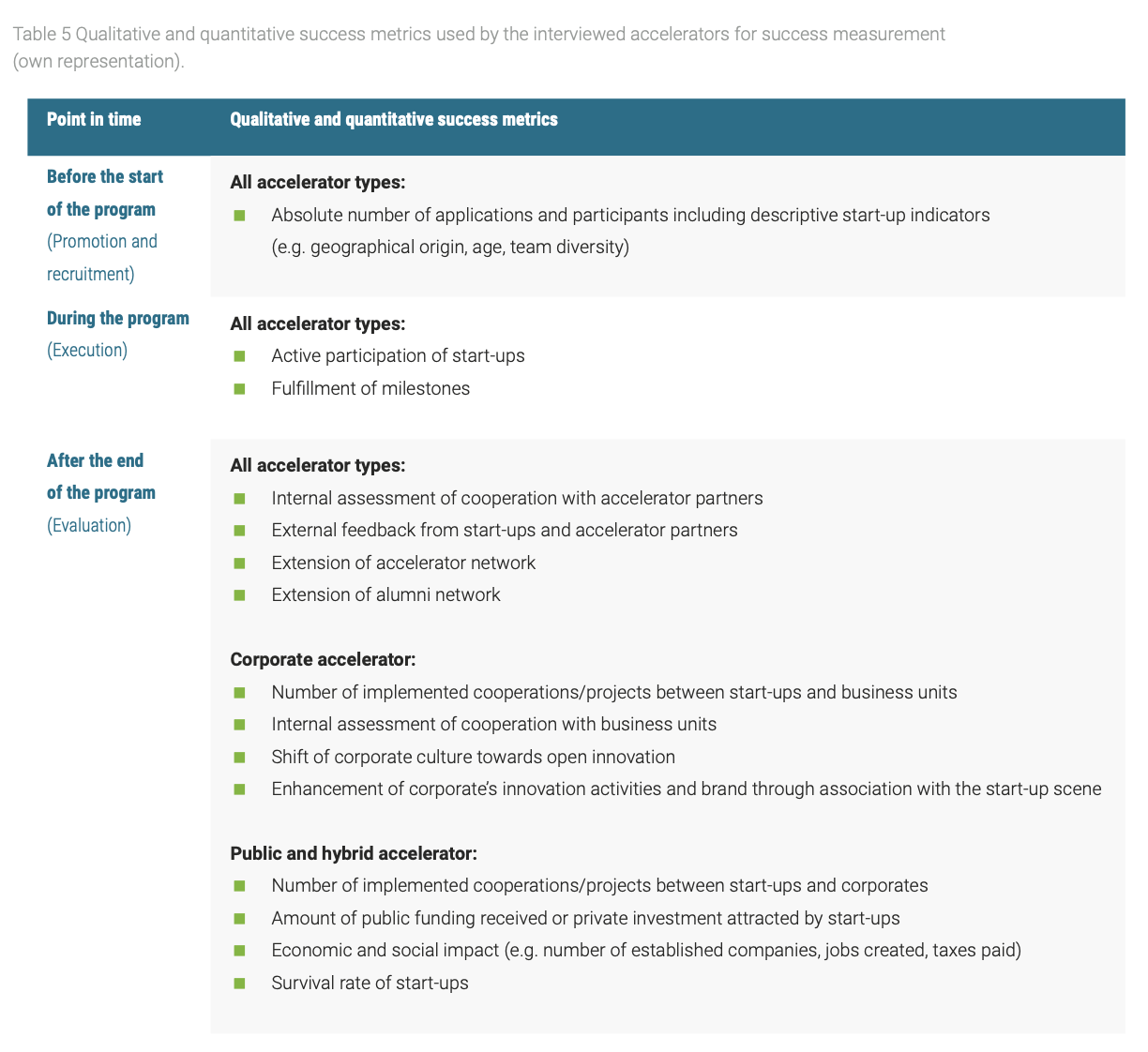

2.3 Success measurement

In this study, success measurement concerns the qualitative and quantitative success metrics of the interviewed accelerators, which are used for measuring the achievement of their objectives. Regarding the measurement of an accelerator’s success, Leatherbee and Gonzalez-Uribe (2018a) emphasize the relevance of selecting the right key performance indicators (KPIs) to assess its progress, even though these KPIs can vary strongly among different programs depending on the accelerator type and its goals. As a result of a systematic literature review, Crișan et al. (2019) found that the top four outcomes at accelerator level are the number of applicants, number of participants, survival rate of start-ups, and funds provided to start-ups. Concerning different accelerator outcomes, Bliemel et al. (2019) differentiate between the participating start-up’s growth metrics (follow-on funding, revenues of start-ups, job creation, new customers, exit valuation multiples, and survival rate), the accelerator’s operational metrics (satisfaction, application numbers, and the number of mentors), and the accelerator’s productivity measures (e.g. occupancy rate or profit margin).

For corporate accelerators, Richter et al. (2017) found that they rarely use success and performance metrics (e.g. such as KPIs), although they are important for the management

of the program. In literature, a lack of performance metrics could be a result of confidentiality reasons as corporates are unwilling to share their internal KPIs (Richter et al., 2017). However, corporates must measure the success of their investments concerning the return on investment (ROI) and achievement of strategic goals (Richter et al., 2017). In doing so, KPIs play an important role in measuring the success of and justifying financial spending for the program. Therefore, corporate accelerators may not only be interested in measuring the satisfaction of participating start-ups and their success, but also the contribution to strategic goals in terms of accessing new markets or increasing market share, the cost effectiveness of the program and what has been learned (Richter et al., 2017). Indeed, Richter et al. (2017) showed that the use of KPIs varies highly among corporate accelerators. Some corporate accelerators implemented KPIs, while others found them useless.

In general, publicly funded accelerators tend to have KPIs concerning the socioeconomic development of a region like relocation of start-ups, number of jobs created, or taxes paid (Leatherbee and Gonzalez-Uribe, 2018a; Pauwels et al., 2016).

2.4 Research questions

Shankar and Shepherd (2019) suggest that the organizational context (e.g. nature of business, industry) matters for how an accelerator is designed and run. Pauwels et al. (2016) highlight that by focusing on one specific industry/sector, the accelerator management team can develop the required industry/sector-specific knowledge and expertise to identify and exploit the full economic potential of participating start-ups. In this study, we focus on the process industries, which include petrochemicals and chemicals, food and beverages, mining and metals, mineral and materials, oil and gas, (bio)pharmaceuticals, pulp and paper, and steel and utilities (Lager, 2016; Lager, 2017; Lager et al., 2013). Moreover, Pauwels et al. (2016) propose to investigate success factors and challenges faced by distinct accelerator types and to define suitable success metrics for measuring the achievement of their objectives.

Therefore, the following three research questions (RQ) will be discussed by drawing on the theoretical background of this study and the results from qualitative expert interviews with ten accelerator managers:

RQ1: Which accelerator types exist and how are they designed?

RQ2: What are success factors and key challenges of different accelerator types?

RQ3: How do different accelerator types measure their success?

3 Method and research design

3.1 Data collection and sample

To get an in-depth and better understanding of the accelerator types and their design in the context of the process industries, we conducted semi-structured interviews with ten accelerator managers.

The research design follows a qualitative research approach, which includes a literature review as a starting point to identify relevant research questions resulting in the development of a semi-structured questionnaire for this exploratory research.

The developed semi-structured questionnaire consists of five topics, in which the first four refer to the design elements of Pauwels et al. (2016), while the last one addresses the qualitative and quantitative success metrics that are used by the interviewed accelerators to measure the achievement of their objectives: 1) Strategic focus (which includes also the funding structure and organizational governance of the accelerator), 2) Selection process, 3) Alumni relation, 4) Program package, and 5) Success measurement. A definition for each topic was given in the questionnaire to create a common understanding between the interviewer and interviewee.

For the validation of the questions regarding their relevance for research and practice and the questionnaire’s comprehensibility, the final draft of the questionnaire was tested with two researchers and one accelerator manager. No questions were excluded and all questions were evaluated as understandable and relevant. The questionnaire can be found in the appendix.

In this study, the interviewed accelerators exhibit one of the following characteristics: 1) explicitly tailored program for start-ups with a process industry background, 2) program with focus on one or several sectors of the process industries, or 3) program that has no focus on one or several sectors of the process industries, but which is also open for the participation of start-ups with a process industry background.

In total, ten expert interviews with accelerator managers were conducted, which mainly focus on the chemical industry. Relevant accelerators were found in a white paper on European Startup Accelerators in the Chemical Industry indicating 19 programs with a partial or main focus on chemistry and other sectors of the process industries (Asano and Kirchhoff, 2019). For the search of corporate accelerators, statistics regarding chemical companies with the highest turnover in 2017 and 2018 were also used (Hohmann, 2019). Finally, other international and well-known accelerators were approached for an interview, when they fulfilled the required characteristics for this study.

Potential candidates for an expert interview received an invitation by e-mail with a short overview of the study including the key research questions. In total, 30 accelerators were approached. Seven accelerators (23%) declined an interview due to a lack of time. Another reason was the lack of knowledge and a missing relation to process industries. Further, 13 accelerators (43%) did not reply. Finally, ten accelerators (33%) confirmed their interest and participated in this study. The interviewees received the questionnaire in advance. All interviews were conducted between November 2019 and January 2020 with an arithmetic average duration of 47 minutes. The interviews were conducted in German or English, and either by telephone or web call. After their transcription, the German interviews were translated into English. Table 2 provides an overview of all interviewed accelerators for this study.

3.2 Data analysis

For the data analysis, the qualitative content analysis of Mayring (2016) was conducted due to the exploratory nature of this research (Krüger and Riemeier, 2014). All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Subsequently, they were transformed into a coherent written text. Then, data were coded based on the design elements and constructs of Pauwels et al. (2016) and new codes were added as long as novel aspects occurred. This process has an iterative character and data interpretation depends on the researcher (Mayring and Gläser-Zikuda, 2008; Ramsenthaler, 2013). The objectivity and quality of results can be improved through interrater-reliability (Krüger and Riemeier, 2014). Therefore, a second researcher checked and verified the coding of the qualitative content analysis. The software tool f4 by audiotranskription was used to support the data analysis. For triangulation of data, information was gathered from the respective websites of the interviewed accelerators.

4 Findings and discussion

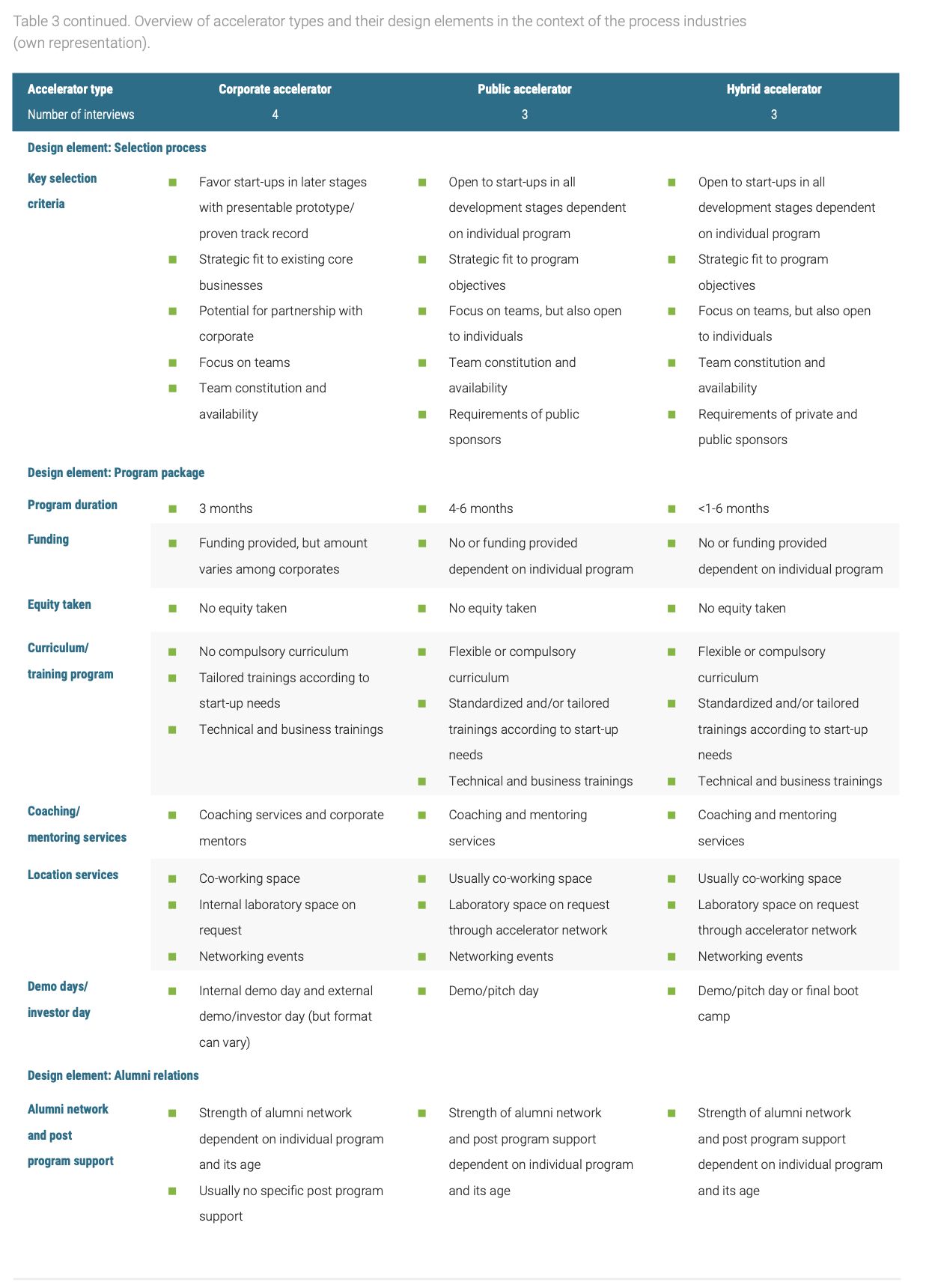

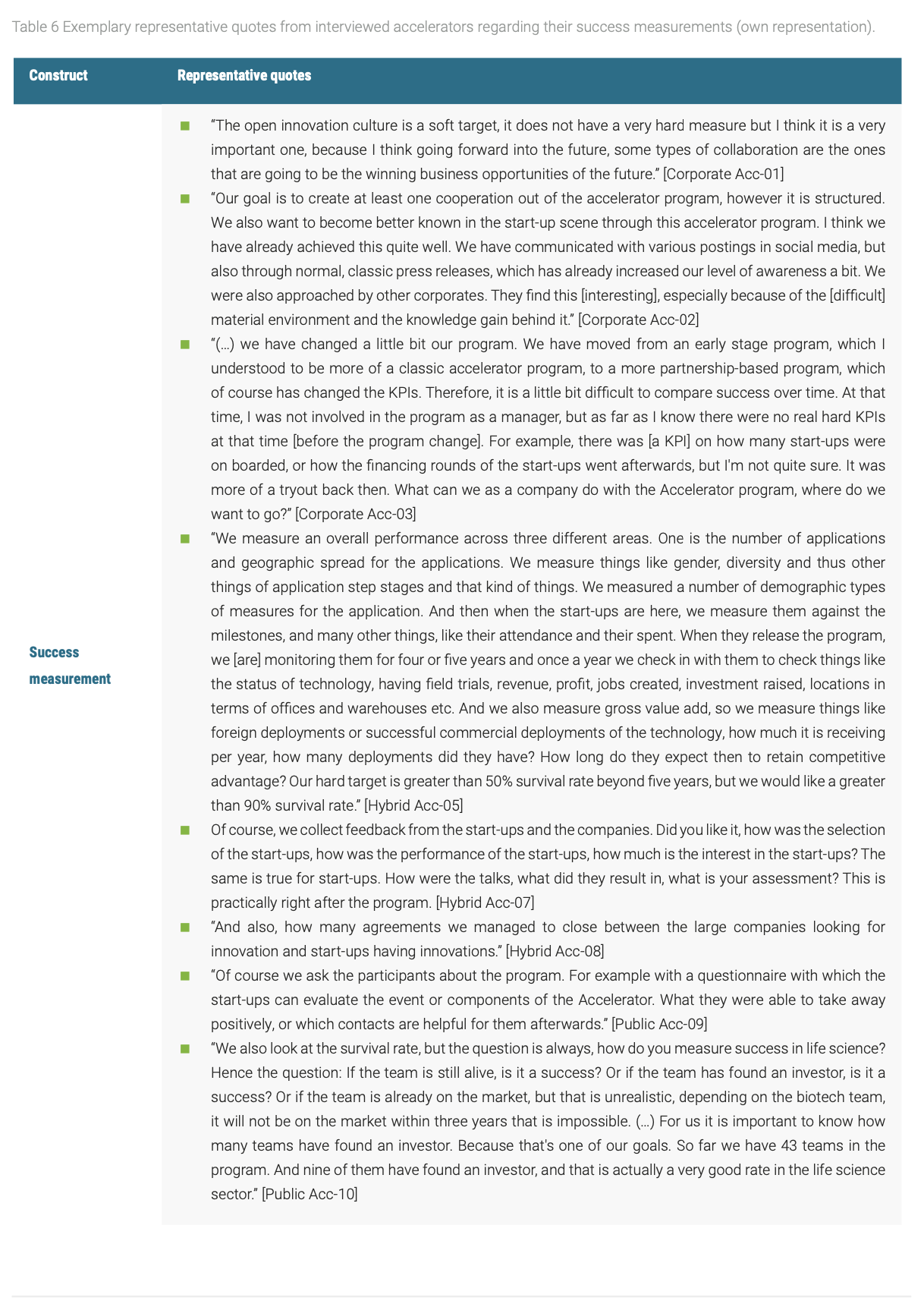

Our data revealed three different accelerator types in the context of the process industries: 1) Corporate accelerator, 2) Public accelerator, and 3) Hybrid accelerator. The two authors compared and discussed all cases based on the five design elements of Pauwels et al. (2016) which allowed for comparability among the interviewed accelerators. The accelerator types were then clustered based on the funding sponsor. This construct belongs to the design element funding structure and governance. Table 3 provides an overview of the three different accelerator types with their differences and similarities concerning the five design elements of Pauwels et al. (2016). Further, Table 4 contains exemplary representative quotes from interviewed accelerator managers regarding their strategic goals and industry/sector focus. Table 5 gives an overview of the qualitative and quantitative success metrics that are used by the interviewed accelerators at three different points in time: 1) before the start (promotion and recruitment), 2) during (execution), and 3) after the end (evaluation) of the program. Some success metrics are used among all three accelerator types. Finally, Table 6 shows exemplary representative quotes from interviewed accelerator managers concerning their qualitative and quantitative success metrics that they use.

In the following, each accelerator type is described in detail.

4.1 Corporate accelerator

4.1.1 Funding structure and governance & Strategic goals and focus

The corporate accelerator is an accelerator type, which is funded and set up by a single corporate with the strategic goal to collaborate with start-ups in mainly exploitative (and less explorative) projects, what means that start-ups offer solutions that are related to the corporate’s current business activities and specific internal problems. Thus, start-ups are selected based on the corporate’s business unit needs as highlighted by accelerator manager Acc-06: “(…) we are looking for new technologies and solutions that can either complement our existing portfolios or improve our current processes and products.” In addition, some interviewed corporates search new business models, and have the aim of enhancing their brand and marketing, while also increasing their visibility in the start-up scene as stated by accelerator manager Acc-02: “We also want to become better known in the start-up scene through this accelerator program.”

The industry/sector focus varies among the interviewed accelerators. Some focus on one, whereas others on several industry sectors or topics. Regarding the geographical focus, corporate accelerators are open for applications of national and international start-ups, while the program normally takes place in one physical location. Normally, the accelerator is located at the corporate’s headquarter.

Usually, internal stakeholders of the corporate accelerator are top management and the financial sponsors of the program (e.g. corporate and business units) as stated by accelerator manager Acc-02: “[The financial sponsoring] is decided on a group level by the board, which of course had to stay behind the project [accelerator program], because we needed the backing of the top management. Then, there is a business sponsor that is a Business Area [Business Area holds several Business Units].” With the exception of corporate Acc-06, an internal accelerator team is responsible for the program consisting of a maximum of three full time employees (FTEs), who mostly come from the corporate innovation department and receive additional support from temporary employees such as working students. The accelerator team members normally have a broad network within the corporate to identify relevant business units’ needs and to facilitate communication between internal partners and start-ups. In three of the four cases, the accelerator was internally set up, either within the corporate innovation management department or in a separate department that reports to corporate innovation. In contrast, corporate Acc-06 was established as an independent entity of the corporate, and the accelerator team consists of nine to ten FTE. In this context, accelerator manager Acc-06 mentions the advantage of greater flexibility, since the accelerator is not part of the corporate structure: “We [accelerator] are a separate company, which can therefore also act more flexibly. We are therefore a bit more free [in the room for maneuvers] than in a normal group structure, and we are also responsible for this. We are active since 2013 and our core team consists of nine to ten people.”

4.1.2 Selection process

Corporate accelerators promote their program through social media and other marketing activities, often with the help of external partners. The application for the program is online. They also scout actively promising start-ups and involve external partners in these scouting activities. In the selection process, all interviewed corporate accelerators use internal corporate colleagues from business units, and also often externals for screening and short-listing the applications. Internal corporate colleagues from business units have the appropriate technical and business/industry expertise to assess the start-up’s solution, and are further involved in the final selection of the start-ups. The final selection format varies among the interviewed corporate accelerators (e.g. pitch day, 2-day boot camp with final pitch, or 3-day workshop “launch pad”).

In general, the interviewed corporate accelerators favor start-ups in later stages with an already developed prototype or proven track record, since this is very important for the involvement and cooperation with internal business units as highlighted by accelerator manager Acc-06: “[The start-ups] need at least one reasonable, presentable prototype. Furthermore, they should perhaps even already have their first customers. We have recently (re)oriented ourselves and decided to [choose] start-ups in the later [venture] phase. We have noticed that when [the start- ups] are in the development phase at an early stage, it is very difficult to set up joint pilot projects with our business unit.” Other key selection criteria are the strategic fit of start-ups to existing core businesses and their potential for a partnership with the corporate as emphasized by accelerator manager Acc-01: “(…) The last one was the potential for partnership and that was what we are looking for. We wanted to make sure that whoever we selected was in a place for a partnership. We have one [start-up] for example that was very far already and has a lot of backing from other companies. That is why we score them a little bit lower in that area, because we just [not] wanted contribute to much to them, they had financial and other corporate backers they were working in the space that we are interested, but the train has lost the station is the best way to say it. All of the criteria were very important. You cannot look [at] them in isolation because when there is no potential for partnership it really did not matter if this [start-up] was a great team.” Furthermore, the interviewed corporate accelerators focus on start-up teams and not on individuals. Here, they look at the team constitution, its availability, and willingness to participate in the program.

4.1.3 Program package

During the program, the participating start-ups receive funding from the corporate, but the amount of funding varies among the interviewed programs. No interviewed corporate accelerator takes equity in exchange. Also, the programs have no compulsory curriculum, rather they offer tailored trainings according to the technical and business needs of the participating start-ups. Furthermore, they provide coaching services and corporate mentors. These corporate mentors help start-ups to find their way through the corporate structure to connect with the right internal colleagues as noted by accelerator manager Acc-01: “We also have what we are calling corporate mentors. Each start-up has two to four corporate mentors, and it is our job to make sure that they have a good connection with our corporation. (…) Being the one point of contact to the start-up so that they do not have to find their way through a larger organization like ours, because that would be very difficult from outside.” Regarding the location services, the interviewed programs provide co-working space, laboratory space on request, and networking events. Finally, the program normally ends with a (internal or external) demo/investor day at which the start-ups present their solution to business units, potential customers or investors. All interviewed corporate accelerators have a duration of three months.

Concerning the program package, accelerator manager Acc-03 summarizes the benefits of their corporate accelerator for participating start-ups as follows: “For most start-ups it is important to have access to our internal resources. Like internal employees, internal experts, customers from us, processes from us that is as an extern not so easy to get. And that, I believe, is our USP as an accelerator program. I think the motives are relatively obvious. We are the only accelerator program in the world that can give start-ups access to our company. And for the most of the start-ups we work with, the motive is to win our company as a business partner, customer or development partner. This is a door opener to our ecosystem. [Therefore,] I think that the financial aspect [50,000 Euro funding without shares] is not the most important aspect for the start-ups participating in our program.”

4.1.4 Alumni relations

After the end of the accelerator, no interviewed corporate accelerator provides any post program support. If no cooperation between a start-up and a business unit is achieved, no further assistance to the start-ups is provided. However, the interviewed corporate accelerators include the start-ups in their alumni network. The strength of the alumni network depends on the individual program and its age. No interviewed corporate accelerator has a structured alumni network program in place as one accelerator manager Acc-01 exemplarily states: “If there is an opportunity to go forward with anyone of these [it has to be mutual] than we would do that individually afterwards. If not, and that is fine, we leave it. (…) To put them in our network in a way that we can always reach out in the future if needed and they can do the same [makes sense].”

4.1.5 Success factors and key challenges

The interviews with the four corporate accelerators revealed that the commitment and involvement of top management for the program is very important. Kohler (2016) also found that top management engagement is crucial to enable open innovation with start-ups and to prevent that start-ups end up in interest conflicts with current businesses. Therefore, the CEO’s support will increase the internal buy-in of business units and involvement of employees, since corporate employees are usually involved on a voluntary basis. Hence, it is important to keep their time involved to a minimum, while identifying the relevant business unit needs for the search of suitable start-ups, or when involving them in the selection process to assess strengths and weaknesses of interesting start-ups. The early involvement of business units in the selection process increases the commitment and acceptance of internal partners for the program. In addition, Kohler (2016) highlights that an early involvement of business units can help to mitigate challenges when setting up a follow-up project between a start-up and a business unit after the end of the program. This aspect is also emphasized by accelerator manager Acc-03 as follows:

“With our [program] form that we currently have, it is very important that we work closely with our internal partners. The internal experts have no specifications in their KPIs, they do not have to work with us. We are dependent on the goodwill and curiosity of our [internal] partners. We try to involve our partners as early as possible in the process, because they are the ultimate customers of the service we offer [as accelerator]. It is important to have a good relationship with the partners and also to integrate the internal partners as early as possible in the whole process so that no misinterpretation occurs. Therefore, at the beginning of our scouting phase, we always consult with the business development teams of the different sectors and with various technology scouts. We then summarize roughly what the business sectors are currently working on and which topics are of interest to them. Whatever topics are on the strategic roadmap. And we also communicate this to experts that we are actively looking for start-ups in these areas. [Hereby] we try to arouse the interest of internal partners as early as possible. When the internal partners find start-ups they are interested in, they are usually willing to participate in such Boot Camps [of our program]. We also try to keep the time [of the experts] to a minimum. Therefore, they do not have to keep the two days free, but one to four hours [for the Boot Camp].”

Moreover, corporate mentors are very important that help and guide start-ups through the complex corporate structure and its decision making process, while connecting them with the right colleagues (Pauwels et al., 2016).

Success stories are very important for the internal and external promotion of the accelerator in order to attract high-quality start-ups, to increase internal involvement of business units, and in order to extend the program as mentioned by accelerator manager Acc-01: “How to say going forward, you [need to] have really huge success and then say we can duplicate this with dedicated FTEs and resources to be able to execute [by an own department]”.

Concerning the key challenges, the interviews revealed that a clear communication about goals and coordination of activities among internal and external partners is necessary as described by accelerator manager Acc-03: “[A shared culture of communication] is indeed not easy, especially when it comes to setting it up in such a way that clear communication exists, so that it is not confusing for the start-ups on the one hand, and for the [accelerator] partners on the other. (…) I believe that you simply have to communicate this well beforehand and be clear about what agenda your partner might also have and address it openly so that there are no conflicts of goals afterwards.”

Furthermore, a short program duration represents a challenge for the development of physical solutions that may require more time, and hence suitable start-ups must be carefully selected as indicated by accelerator manager Acc-02: “We firmly believe that it is simply much more difficult to create an accelerator program that promotes hardware-related start-ups. (…) This is also the feedback we have received from the start-ups. We have learned from the feedback that accelerators are mainly designed to sharpen the business plan [with] relatively fresh [start-ups] and perhaps also to perform a POC [proof of concept] as part of a software solution. But to get some results in the hardware environment within a short period of three months is actually quite difficult. That is why you have to take a close look at the project.”

4.1.6 Success measurement

One key success metric of the interviewed corporate accelerators is the establishment of cooperations and implementation of projects between the participating start-ups and its internal business units after the end of the program as emphasized by accelerator manager Acc-03: “For us, the most important KPI is “Qualified cooperation projects according to the accelerator program”, i.e. how many start-ups per batch could we really link to internal partners and then initiate cooperation projects with the start-ups.” In this context, they also assess the cooperation with the corporate’s business units. Another rather qualitative success metric is the shift of the corporate culture towards open innovation as stated by accelerator manager Acc-01: “The open innovation culture is a soft target, it does not have a very hard measure but I think it is a very important one, because I think going forward into the future, some types of collaboration are the ones that are going to be the winning business opportunities of the future.” In addition, they use general qualitative and quantitative success metrics concerning the absolute number of applications and participants, active participation of start-ups and fulfillment of milestones during the program, or assess the cooperation with accelerator partners and stakeholders, and gather their feedback.

The corporate accelerator type and its further classification into sub-types was already found and discussed in existing literature (Kohler, 2016; Moschner et al., 2019; Pauwels et al., 2016; Prexel et al., 2019). Pauwels et al. (2016) found that the ecosystem builder type is set up by a corporate to develop an ecosystem around the corporate consisting of customers and stakeholders. In contrast, in our study, corporate accelerators rather search start-ups with solutions that help business units to exploit current businesses and existing technologies, or to solve specific internal problems. Hence, they do not directly aim at establishing or enhancing the corporate ecosystem, although start-ups may become potential suppliers or customers of the corporate or part of the corporate’s ecosystem through the alumni network. Our findings are in line with the strategic goals and characteristics of a corporate accelerator sub-type “In-house accelerator” described by Moschner et al. (2019). In accordance with Richter et al. (2017), we also found that the use of success metrics varies strongly among the different interviewed corporate accelerators.

4.2 Public accelerator

4.2.1 Funding structure and governance & Strategic goals and focus

The public accelerator type is funded by local, national or supranational (e.g. European) funding schemes, and thus has public authorities as main stakeholders. The strategic goal of the public accelerator is to enhance start-up activity and in doing so to foster economic growth within a specific region (e.g. federal state or country), either without or by specializing on a specific sector or topic (e.g. technological domain). In this context, the main strategic goal is the attraction of entrepreneurial talent and the local settlement of start-ups, and to facilitate the transformation of scientific inventions into innovations by supporting the creation of local spin-offs (e.g. from research institutes or universities). In general, the interviewed publicly funded accelerators also aim at the development of rather explorative and novel technologies. This should contribute to a diversification of the local economy, while increasing the competitiveness of the respective region and reducing the dependence on a single industry. Therefore, the interviewed publicly funded accelerators are open for national as well as international start-ups with promising solutions, but start-ups must participate on-site in the program. The program takes place in the region or country in which it is funded. Accelerator manager Acc-09 summarizes this as follows: “[Our goal] is to promote start-ups in the field of natural sciences with a focus on material science here at the site. And, of course, because it is a publicly funded program, it is also intended to facilitate and promote the establishment [of start-ups] at the respective location. This is clearly one of the program’s goals, which is why one of the prerequisites for participation is the interest in founding a company or the establishment of a company in the state.”

The organizational governance of the three interviewed publicly funded accelerators was organized differently. In one case, an independent entity with 20 FTEs was responsible for running the accelerator, whereas in the other two cases, the accelerator was run by a technology park and a research institute at a university with less FTEs.

The industry/sector focus of the interviewed public accelerators is partly very broad and covers various different topics depending on the individual program.

4.2.2 Selection process

Public accelerators use several channels to promote their program including social media activities and through their accelerator network consisting of partners, mentors and other relevant stakeholders. For the scouting of suitable start-ups for their program, they exchange with universities, incubators and technology transfer units. The application for the program is online. In the selection process, all interviewed public accelerators use externals for screening and short-listing the applications. These externals are often industry representatives, mentors/coaches, alumni or investors from the accelerator network and possess the necessary technical and business/industry expertise to appropriately assess the applicants and their fit to the program as accelerator manager Acc-10 describes: “And finally, we forward the applications [which have not been filtered out by us beforehand] to our jury, which ultimately makes the decision. This jury examines the start-ups more intensively, for example with regard to patents, if the teams have patents. The jury consists of three people. These are industry experts on the one hand and patent experts from technology transfer offices on the other. Sometimes mentors from large business plan competitions such as ScienceforLife also participate. They have already seen many start-ups and know whether [the solutions of the] start-ups are up to date or whether they have simply been there ten times before.” These externals are also involved in the final selection of the start-ups at a pitch day.

The interviewed public accelerators are generally open to start-ups in all development stages, and hence the maturity of solutions of the participating start-ups may differ strongly. Accelerator manager Acc-09 considers this as an advantage of the program, since start-ups can learn from each other and provide feedback to their peers: “Whereby we have now noticed from the experiences of the Pilot Accelerator that it really works surprisingly well when the teams are in different phases. In the pilot project, we had two teams that had not yet been established, but were still carrying out a spin-off as a start-up project at an institute or research institution. Then, we had a start-up that was already established, and a start-up that was established during the course of the accelerator. It was really astonishing how good these different perspectives are for both the young or still current start-up projects and the participants who have not yet founded a spin-off. Simply because you get feedback from the more experienced participants where there are still stumbling blocks and you should take a closer look. (…) On the other hand, it was also astonishing to see that even the young start-up projects or those that have not yet been established were able to offer added value to those who have already started up. This is simply because one has a completely different view of the product. And above all, and this is ultimately also a characteristic of these founders, that there is a high level of professional expertise. And through this, the young founders can also give feedback on the products of the already founded companies, at least from their professional perspective. This means that biochemists can now provide feedback on start-up projects that focus on genetic aspects. This means that there is a surprisingly good network and added value for both sides.”

In general, the interviewed public accelerators rather focus on start-up teams, but are also open for individuals and help those to find the right team members. In fact, the team constitution, availability, and willingness to participate in the program are important selection criteria as highlighted by accelerator manager Acc-09: “The diversity of the team also plays a role. This means that if [the members of the team] are purely scientific, experience shows that it is more difficult than start-ups with members who have a clear economic background. [It is also important] whether the team consists of several founders. If there are one or two people involved in the start-up, this tends to be more difficult than if there are perhaps already three or four founders who can share the tasks accordingly. [At best, the founders] have different professional focuses and a different appearance. Because especially for the first start-up phase it is crucial how well the team works.”

For the intake in the program, start-ups must also fulfill requirements of the public sponsors (e.g. local settlement and physical participation in the program on-site).

4.2.3 Program package

Regarding the program package, two of three cases do not provide any funding for participating start-ups. However, participation is free of charge. The third case provides up to 80,000 US$ of funding, but takes no equity in exchange. Furthermore, the interviewed public accelerators have either a flexible or standardized curriculum. Accelerator manager Acc-04 compares the curriculum and organization of their program with the structure of a university course: “Mainly every week [the start-ups] have activities. We will give them something that is called a playbook. The playbook is basically everything that is going to happen inside of the accelerator. When they start the first day, they will have a calendar with all the activities that they will have during the program until being at the [end of the] program. They have activities pretty much every day. You have sessions, you have workshops, you have talks, you have events, you have mentor hours. Everything is planned ahead. Think about the accelerator is like going into a university. You are coming to the university, you start your workshops or whatever, they will give you a plan of the course that you are taking, right? It is a kind of this scheme.” Therefore, standardized, but also tailored trainings according to the start-up needs are offered as indicated by accelerator manager Acc-10: “[In our program] we accept life science start-ups, and they come from the biotech, medical technology and digital health sectors. (…) These start-ups have very special needs, which are very different from e.g. IT start-ups, simply because the market in the business is very complex and also very regulated.” In addition, both, technical and business trainings are offered. Besides, the interviewed public accelerators provide coaching and mentoring services. Concerning the location services, they usually offer co-working spaces and networking events. Access to laboratory space can be provided on request through the accelerator network (e.g. at a university or research center) as described by accelerator manager Acc-09: “We do not offer offices, but a co-working space is available. Because we are working together with the research facilities on campus and also want to set up a workshop ourselves, laboratories and workshops will be available for the teams during their participation in the project. For this purpose, we have also planned the necessary personnel, who will also be available in the workshop, for example. This means a technical assistant who will give an introduction to the workshop, an introduction to the equipment that has perhaps not yet been used, so that a competent person will be available there to supervise this. And in the laboratories it can then be a possibility to give something like a training or workshop with the experts from the research institutions. For areas that are then relevant for the start-ups. But we do not provide the raw materials themselves.”

Finally, the program normally ends with a demo/pitch day or boot camp at which start-ups have to opportunity to present their solution to potential customers or investors in order to obtain a follow-up investment. In general, program duration varies from four to six months.

4.2.4 Alumni relations

After the end of the program, the strength of the alumni network and post program support depends on the individual program. All interviewed public accelerators highlight the value of a strong alumni network and their efforts to stay in contact with alumni. Successful alumni can promote and support the program as mentors or provide valuable networking opportunities for future participants of the program as accelerator manager Acc-10 illustrates: “We have an alumni program. We write to the alumni regularly. We invite them to our events, also to our Demo Days. Sometimes we also get requests from trade fairs, where we get free tickets and distribute them to the alumni. So we make sure that we stay in contact. Some alumni we have even taken on as mentors, for example if they have a certain expertise.” Accelerator manager Acc-09 states that their program actually consists of two parts. The accelerator is for the fast-track development of a start-up, while a second consecutive program will ensure long-term growth support for the start-up’s scale-up and internationalization activities: “Now in the new planning [of the Accelerator] we will have this Accelerator Program [as compact support], but after the end of the class [cohort] the support will not stop, but a further support of the start-ups will take place via this longer-term [growth program] with further individual coaching or also topics on internationalization. In other words, this program is actually two-track. On the one hand we have the Accelerator Program and on the other hand this further growth support.”

4.2.5 Success factors and key challenges

Success stories of alumni are very important for public accelerators to demonstrate their added value for society in terms of increasing start-up activity and fostering economic growth within a specific region and justifying the spending of public funding. For the attraction of promising start-ups, success stories and a strong accelerator network including high-quality coaches and mentors, industry representatives, investors, and alumni are essential.

A key challenge for public accelerators is the search for financial sustainability to reduce dependency on public funding. For this reason, this accelerator type must experiment with their funding structure and revenue model to secure existing, but also to attract new funding sources to ensure the continuation of the program (Pauwels et al., 2016).

4.2.6 Success measurement

The interviewed public accelerators measure their success in terms of positive impact on the socioeconomic development of a region as summarized by accelerator manager Acc-04: “We measure everything basically. Our KPI regards to global ecosystem impact, economic impact and social impact like employment, taxes gathered by the public sector through the sales that start-ups are making.” Additionally, one important success metric is the survival rate of start-ups, which participated in the program. However, this can be difficult to measure and is only possible after some time, since development processes within the process industries may especially require some time as indicated by accelerator manager Acc-10: “We also look at the survival rate, but the question is always, how do you measure success in life science? Hence the question [is]: If the team is still alive, is it a success? Or if the team has found an investor, is it a success? Or if the team is already on the market, but that is unrealistic, depending on the biotech team, it will not be on the market within three years that is impossible.” Further, they also use general qualitative and quantitative success metrics regarding the absolute number of applications and participants, active participation of start-ups and fulfillment of milestones during the program, or internally assess the cooperation with accelerator partners and stakeholders, and gather their feedback concerning the program.

In our study, the public accelerator type is similar to the welfare stimulator type that was found by Pauwels et al. (2016), but differs slightly in the definition of the different design elements. The success metrics used by the interviewed public accelerators are similar to those mentioned by Leatherbee and Gonzalez-Uribe (2018a) and Pauwels et al. (2016).

4.3 Hybrid accelerator

4.3.1 Funding structure and governance & Strategic goals and focus

The hybrid accelerator type has multiple funding sources coming from private and public sponsors. Two cases were initiated by the national government, which also contributes some funding, while the main share of funding is coming from several corporates that also provide support for the program. In contrast, the third case was initiated by a private university. Here, the program is funded by the university itself, but also by multiple corporates and regional public funding as described by accelerator manager Acc-08: “We are a university based center for entrepreneurship [institute]. (…) Most of the budget is coming from the university itself. (…) Then, the second sponsor is the large companies that are looking for innovation. They pay equal to belong to the community, and they also help us defining some of our activities, like events for instance. And generally minor those is a public funding, which [we] receive a little bit of public funding from the local government.” Therefore, this accelerator type has a hybrid funding structure, since program sponsors have different backgrounds.

The strategic goals of the interviewed accelerators vary. All programs have the strategic goal to enhance start-up activity in a specific region (e.g. federal state or country) by specializing on a sector or topic (e.g. technological domain) to foster economic growth as accelerator manager Acc-07 summarizes: “Our hub is focused on the topics of [digitalization of] chemistry and pharmacy in order to simplify, enable and support the cooperation between start-ups and established corporations, especially in the respective country. (…) Furthermore, the visibility of the chemical industry and digitalization is important to us. The chemical industry is relatively in the early stages of digitalization, and does not have a huge visibility in the start-up scene.” In the case of the private university initiated accelerator, accelerator manager Acc-08 highlights that the program has two strategic goals. First, they want to enhance the brand of the university regarding entrepreneurship and innovation, and second, they want to educate skilled entrepreneurs for the regional economy: “Being in the 21’st century, the university realized some years ago, that you cannot leave university without that area on entrepreneurship and innovation with reference in scientific, technical areas. [It is] a question of official branding. (…) Our mission is to help to develop the next generation of industrial companies, which create a competitive economy and reinforce the industrial sector. (…) our focus is to help creating industrial companies. Because we are in a region with traditional industries. [And a region] with a strong industrial sector, those [industrial companies] create qualified jobs and (…) competitive economies.” All interviewed hybrid accelerators have the aim to attract entrepreneurial talent for the local establishment of start-ups in the respective regions. Therefore, in all three cases the program takes place in the region or country in which it is funded. In general, all interviewed programs have a focus on one or several related industry sectors/topics. In doing so, they rather focus on the development of explorative and novel technologies, and are open for national and international start-ups.

The organizational model for the governance of the accelerator was different for every case, ranging from a hub that was initiated by a national government and multiple corporates, a technology center, and a private university. The accelerator team consists of maximum four FTE and is supported by additional staff (e.g. working students).

4.3.2 Selection process

The interviewed hybrid accelerators promote their program through social media activities and their accelerator network. For the scouting of suitable start-ups for their program, they exchange with and are supported by the corporates that partly fund the program. The application for the program is online. For the screening and short-listing of applications, all interviewed hybrid accelerators use externals during the selection process. These externals are industry representatives from the corporates that fund the program, but also mentors/coaches, alumni or investors from the accelerator network, which possess the relevant technical and business/industry expertise for the assessment of applicants as accelerator manager Acc-05 indicated: “When the application [phase] is closed, we bring in experts like entrepreneurs, investors, oil and gas experts and executives, who review all the application with us and score each of the videos up to ten.” This is also stated by accelerator manager Acc-07: “[Within the selection committee] are usually people from the fields of digital innovation, digital transformation and technology scouts. One company, for example, provide the Head of Digital Transformation as a member of the committee. The managing director from our hub is also participating, who worked for one of the companies for 21 years. He has a relatively good feeling about whether or not it can be exciting for such companies. For special areas such as cosmetics, for example, we try to make contact with the corresponding division of one of the companies to ask: Hey look at that, would that be exciting for you?” These externals are also involved in the final selection of the start-ups at a pitch day.

The interviewed hybrid accelerators are generally open to start-ups in all development stages, which have a strategic fit to the program. The maturity of start-up’s solution may differ strongly. However, accelerator manager Acc-08 mentions that a functional prototype is very important in the context of manufacturing industries, since the focus of their program is the up-scaling of production: “From a maturity perspective, the product should be already a functional prototype, so a TRL-5 [technology readiness level] (…) the case of the prototype is because, the focus of the program is to industrialize start-ups that produce very few units, and the next challenges is to produce 500 units or 5000 units. If you don’t have a prototype you are too early for us.” In general, they rather focus on start-up teams, but are also open for individuals and help them to find the right team members as stated by accelerator manager Acc-05: “We do consider single founder teams. We have experiences so far in both cohorts and being successful in helping them [to] build a good team. So, we are quite happy to take a single founder assuming an exciting technology and a good impact and a strategic fit.” Most teams do indeed consist of at least two members. The team constitution, availability, and willingness to participate in the program are important selection criteria as stated by accelerator manager Acc-08: “And the last element is the team, [it] should have full-time committed into the venture, so they should not be in five projects. (…) And the question of having a full-time committed team is, because the experience tells us that when they are working on something else, then they neglected the project. The start-up is not developing in that case that it should be developing.”

Finally, for participation in the program, start-ups must also fulfill requirements of the corporate and public sponsors of the program.

4.3.3 Program package

Concerning the program package, two of three cases do not provide any funding for participating start-ups. The third case provides up to 100,000 £ of funding, but takes no equity in exchange. In all cases, participation is free of charge. Besides, the interviewed hybrid accelerators have either a flexible or standardized curriculum depending on the individual program. In addition, standardized, but also tailored trainings including business as well as technical trainings are offered based on the needs of the start-ups. For start-ups with an industrial background, which like to set-up a production, accelerator manager Acc-08 highlights that start-ups require very specific knowledge and trainings regarding the manufacturing of their solution what is not covered by “usual” accelerators that merely focus on business aspects: “This is typically how they arrived to us. And they already went to a couple of accelerator programs. But the acceleration programs that’s also a bit the thing, [it] is useful coming from acceleration programs. 98 % of acceleration programs that exist out there, they are suddenly the same. They have the same kind of structure and they all look on the business model, the competitive landscape and things like that. Which is great. But our problem goes into more mature faces, where these things are clear and you need to manufacture. Actually, it is a very complex process, and no one explains how to do that. (…) we have some curricula sessions so classic lectures, but they are very practical, we call them workshops, because they are very hands-on. And they are typically very much manufactory-oriented and product-oriented, so this is about product testing, product validation, product certification and things like that.” Moreover, all interviewed hybrid accelerators provide coaching and mentoring services, who help the start-ups to further develop their market solution as stated by accelerator manager Acc-08: “Then, we have the coaching/mentoring sessions, so we have head of innovations of large industrial companies and entrepreneurs (…) coaching these entrepreneurs [start-ups].” Regarding the location services, the interviewed hybrid accelerators normally provide access to co-working spaces and organize networking events with relevant stakeholders as accelerator manager Acc-08 indicates: “And the third activity that we are running is a community of 30 heads of innovations (…) some of them [are from] chemical companies, but then [also from] other industrial companies, automotive companies or (…) water treatment companies, larges in that field companies, that are looking for innovation outside their boundaries. (…) Either the large company would invest on them [start-ups], or look for ways to acquire license technologies, so that [they] can exploit that technology or to co-develop to tackle that problem [of the company].” Laboratory space is not provided by the accelerator as part of the program, but could be provided by relevant contacts of the program as mentioned by accelerator manager Acc-05: “We have workspaces. (…) We also offer the start-ups IT services, tools, infrastructures. (…) We have not the ability to offer laboratories and we do not offer raw materials or chemicals (…) But we are able to signpost them into universities or some place that might be able to help, but that is not something that we offer as part of the program, we connected them with people that might be able to help.”

At the end of the accelerator, the program culminates with a demo/pitch day. Program duration varies from less than a month up to six months depending on the individual program.

4.3.4 Alumni relations

After the end of the program, all interviewed hybrid accelerators have an alumni program, whereas the strength of the alumni network depends on the individual program as exemplarily stated by accelerator manager Acc-08: “We do have an alumni network, we do activities with them, but it is also true, that we could do a better job there. There are some cohorts, [where the relationships] become strong, and we have groups of within social media apps and some cohort are super active. We do have a community, we meet few times a year to gather together and to have BBQ [Barbecue] and we have drinks and things like that, but these are areas that we would like to reinforce actually.” One case also provides post program support in form of an incubator as indicated by accelerator manager Acc-05: “After we finish the 16-week accelerator program, we also provide a follow-on program [incubator] for two years. [Here] we give them additional co-working space, board rooms, support and we also give access to additional funding (…) through our institution.”

4.3.5 Success factors and key challenges

The involvement of corporate sponsors is crucial for the successful selection of suitable start-ups for the program. Therefore, a close communication with corporate representatives is necessary to identify their needs and to involve them early in the selection process. This can ensure their commitment and support for the program. Success stories of collaborations between start-ups and corporates can help to promote the accelerator within the sponsor organizations and to increase interest in the program. In this context, accelerator manager Acc-07 emphasizes that the start-ups as well as corporates must have a serious interest in the program: “An often-underestimated criterion during the selection process is that both sides [start-up and corporate] should be interested in our program.” Besides, successful alumni can attract promising start-ups for the next batch of the accelerator. These success stories can also demonstrate the added value of the accelerator to public authorities, which provide public funding for the accelerator. Finally, hybrid accelerators must experiment with their funding structure and revenue model to secure financial sustainability as mentioned by accelerator manager ACC-05: “Our institution has a ten-year life cycle, two years are into that [now]. We have aspirations for obviously our accelerator program and another program of our institution be leaf beyond that and continue to add value, so to do that we are needed to become an independent entity or some point with the own funding mechanism.”

4.3.6 Success measurement

For the interviewed hybrid accelerators, a key success measurement is the positive impact on the socioeconomic development of a region. Accelerator manager Acc-05 summaries their key success metrics as follows: “When they release the program, we [are] monitoring them for four or five years and once a year we check in with them to check things like the status of technology, having field trials, revenue, profit, jobs created, investment raised, locations in terms of offices and warehouses etc. And we also measure gross value added, so we measure things like foreign deployments or successful commercial deployments of the technology, how much it is receiving per year, how many deployments did they have? How long do they expect then to retain competitive advantage?” Since corporates are also funding sponsors of the interviewed hybrid accelerators, another key success metric is the number of cooperations and projects between participating start-ups and corporates as highlighted by accelerator manager Acc-08: “(…) And also, how many agreements we managed to close between the large companies looking for innovation and start-ups having innovations. Those are indicators for us.” Regarding general success metrics, the interviewed hybrid accelerators measure the absolute number of applications and participants, active participation and fulfillment of milestones during the program, and collect feedback from participating start-ups and accelerator partners, while also internally assessing the program.

Pauwels et al. (2016) found that accelerator types exist, which exhibit characteristics of two different accelerator types. Our findings are in line with this. Moschner et al. (2019) identified a corporate hybrid accelerator, but this corporate model includes both external start-ups and internal innovation projects from corporate employees in the same program, and thus does not fit to our findings. Moschner et al. (2019) also revealed a consortium accelerator type. Here, an external accelerator provider offers its services to several corporates (e.g. Startup Autobahn). This definition does not fit to our findings neither, since our cases also have public program sponsors. In addition, our cases pursue distinct strategic goals compared to the consortium accelerator type described by Moschner et al. (2019). For this reason, the hybrid accelerator type that we found extends existing literature, while taking into account either private or publicly initiated programs, which are additionally funded and supported by multiple corporates, and hence exhibit a hybrid funding structure consisting of private and public sponsors. In general, Cohen et al. (2019) mention that accelerators often have multiple sponsors. Consequently, further hybrid accelerator types and models may exist. Concerning their success measurement, the success metrics used are similar to those mentioned by Leatherbee and Gonzalez-Uribe (2018a) and concern the socioeconomic development of a region, however providing interesting start-ups for their corporate funding sponsors is also of high relevance for them.