Internationalisation of SMEs: A Micro-Economic Approach

Abstract: Internationalisation can be crucial to the long-term success of small- to mediumsized businesses, especially since they are expected to show international growth at an early stage. Our research explores whether firms using an opportunistic portfolio approach are more successful in their efforts to internationalise than are firms using the stage and network approaches. Our research may be characterized as a multi-company longitudinal clinical case study using triangulation to analyse data. The sample consists of six Nordic business-to-business, high-technology firms with sales of €100,000 to €10 million. Four of the six firms had significant revenue from the food industry, petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, bulk and speciality chemicals and the pulp and paper industry. The results indicate that the opportunistic portfolio model provides some explanation of how firms can internationalise successfully.

Introduction

It is important to study variables and processes that affect success in internationalisation as small- to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are increasingly competing in the global marketplace. Internationalisation can be crucial to a firm’s long- term success, and the scale of expansion and risks involved are substantial [1]. Internationalisation involves substantial monetary commitments and risks that affect long-term profitability, influence capital allocation among investors, and ultimately, affect stakeholder value. Even primarily domestically oriented SMEs must be internationally competitive to help ensure their long-term viability and success [2]. Numerous strategies for internationalizing operations have been identified and studied, but the results are mixed with regard to identifying successful and/or unsuccessful strategies. Sample selection, methodology, and the confusing effects of strategies employed simultaneously have led to these results. Therefore, applying a single theory or method of internationalisation, such as foreign direct investment, stage theory, or network theory has yielded inconsistent results across firms operating in complex environments.

The internationalisation process is especially important for SMEs that wish to become players outside their domicile. Understanding and managing the process is critical since SMEs are expected to demonstrate international growth at an early stage. Autio, Sapienza, and Almeida [3] showed that the earlier a firm internationalised, the more rapidly it internationalised. To date, most studies have focused on identifying the variables that affect internationalisation. These variables include age, size, growth rate, founder presence, ownership structure, independence, and management preference. It is furthermore important to determine which among many variables and processes affect success in internationalisation. Several studies have focused on models of internationalisation which appear suitable under specific circumstances; few studies, however, have focused on the processes associated with internationalisation. We focus specifically on how the method of internationalisation used affects a firm’s success and how firms manage the process of internationalisation.

This paper contributes to the literature in three main ways. First, it attempts to enhance existing theories by incorporating a risk/return framework. Second, it incorporates longitudinal clinical case research, which helps to enhance our understanding of how SMEs operate. Third, it further develops our understanding of how firms internationalise. We also address some of the criticism of existing studies.

We used a survey instrument combined with interviews and observations of the decision- making processes of several firms. The sample consisted of six privately held Nordic business-to- business high technology firms with sales of € 100,000 to € 10 million. We focused on the method and process of internationalisation and followed the firms for a two-year period.

The term ‘success’ is used throughout this paper and is defined as a percentage of total sales which are international in a one-year increment. Quantitatively, success is defined as international sales of over 30% of total sales on a sustained basis, ‘sustained’ being defined as not experiencing over a 30% decrease in international sales on a year-to-year basis. This is similar to how the literature defines it, with the exception of one stream of research that focuses on performance as measured by increases in share value. As a secondary measure, we consider the number of foreign customers gained by each firm during the study period. According to our measure, all firms were successful during the period of study. Other terms that we use throughout the paper include stage model, network model and opportunistic model. To provide clarity to the reader, definitions of these terms are provided. The term stage model means that firms internationalize using a staged approach. A staged approach may mean that (1) firms start exporting their products and then open offices, building production facilities et cetera. It may also indicate that (2) firms expand geographically in stages, such as first expanding into countries adjacent to the country of origin and then into countries farther away. It may also mean that (3) firms begin expanding into countries with cultural familiarity. In this paper, we define a staged approach as it is defined in (2) above. The network model is used to describe an approach to internationalization where firms utilize networks to access foreign markets. An opportunistic portfolio approach is defined as a regional approach where opportunities within the region dictate effort. For example, a Scandinavian firm may decide to expand into the German speaking part of Europe (the region) but the entry point in the region is determined by the domicile of the first customer. This is in contrast to the stage approach where a firm may decide to expand into Germany, followed by Austria and Switzerland. We argue that this is a riskier approach since a firm may invest in an expansion into Germany without achieving a return. After failure (or success) in the German market, the firm moves into the Austrian market.

This paper is organized as follows. The first section combines a literature review with theory development. This is followed by a discussion of the hypothesis. The subsequent sections discuss the research methodology and principal results, respectively. The final section provides a summary and conclusions.

Literature Review and Theory Development

This section gives an overview of relevant research into the internationalisation of SMEs. Internationalisation has been studied extensively with mixed results. Existing literature dealing with internationalisation of SMEs can be divided into three main theoretical areas: stage theory [4], network theory [5], and foreign direct investment theory. The two former models are applicable to contemporary research in international entrepreneurship. The stage model used by Gankema, Snuif, and Zwart [6] suggests that internationalisation occurs in stages. Bell [7], however, found little support for stage theory and moreover suggested that network theory may have limited merit in explaining the internationalisation process. The network model holds that a firm’s network relationships are the basis for internationalisation [5]. Coviello and Munro [8] suggested that the internationalisation process for small software firms reflected a stage model that is driven, facilitated, and inhibited by network relationships. The foreign direct investment theory literature primarily explains investment patterns [9]. This theory appears to be less applicable to studying the behaviour of specific firms and is only briefly presented in this paper.

The results of studies applying all three of the above theories are generally mixed. Yip, Biscarri, and Monti [10] found that ‘firms on average do not use a systematic approach in their efforts to internationalise’, although the degree of systemisation appears to have affected firm performance. Apfelthaler [11] found some support for the foreign direct investment model, but suggested that individual bias was the major factor in the decision to internationalise. The origin of the bias was not identified. Like Yip, Biscarri and Monti [10], Chetty and Campbell-Hunt [1] also suggested that internationalisation is less likely to be pre-conceived or planned in detail. Andersson [12] found partial support for the stage model, but concluded that entrepreneurial behaviour was the most important factor in efforts to internationalise. Coviello and Martin [13] found incremental support for the network and stage models. They suggested that in internationalizing, the firms they studied used a combination of all three approaches. This indicates a pattern that is more complex than previously thought. Jones [14] found little direct support for the stage model. Instead, the firms in her sample followed their own individual, customized paths of internationalisation. Importantly, she found that resource and knowledge constraints were not as limiting as the stage and network models would suggest. This is similar to the results of Coviello and Martin [13] and Autio, Sapienza, and Almeida [3].

McDougall and Oviatt [15] and Coviello and Martin [13] maintain that there is little consistency in the results of existing research. This inconsistency leads us to believe that researchers need to explore alternatives. We are thus putting forward a fourth model of internationalisation, which we shall term the opportunistic portfolio model (OPM). OPM is based on a portfolio approach where risk is reduced through diversification when a firm enters several countries simultaneously.

Crick and Jones [16] found significant opportunistic behaviour on the part of UK firms attempting to internationalise. Coviello and Martin [13] also found opportunistic behaviour among firms that were in the process of internationalisation. Jones [14] found considerable variation among firms’ internationalisation efforts that could not be explained by firm characteristics. Anecdotal evidence from Jones’ study suggested that market opportunities played an important role in internationalisation. Westhead, Wright, Ucbasaran, and Martin [17] maintained that UK firms in the process of internationalisation did not systematically evaluate alternative entry modes, suggesting widespread use of opportunism.

These studies specifically point to opportunistic behaviour in efforts to internationalise, and suggest that entrepreneurs and owners may view the decision to internationalise as a risk–return decision rather than one based on resource constraints, organizational learning, and networks. Das and Teng [18] suggest that opportunistic behaviour may play an important part in entrepreneurial behaviour, and that long-term entrepreneurial behaviour tends to limit risk-taking while attempting to maximize wealth. Their findings support similar arguments made by Kaish and Gilad [19].

It follows that the OPM approach to international expansion would be most appropriate if entrepreneurs are risk averse or risk controlling. Several recent studies have challenged the assertion of Palich and Bagby [20], who found no difference in the propensity to take risks between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs. Saravathy et al. [21] maintain that the success of entrepreneurs is closely tied to the perception and management of risk. They argue that entrepreneurs focus on controlling outcomes for a given level of risk. Forlani and Mullins [22] found that entrepreneurs tended to select ventures with lower risk profiles. Chicken [23] maintains that entrepreneurs face risk in all aspects of their operations. Major risk factors include economic risks, technical risks, resource related risks, operational risks, and socio-political risks. Brunsson [24] argues that uncertainty will affect decisions about investments, such as decisions to internationalise. Diversification, a form of risk reduction, has also been studied extensively. Qian [25] suggests that firm performance is positively related to early product diversification. Rugman [26] maintains that international diversification offers significant risk- reduction advantages. Kim, Hwang, and Burgers [27] argue risk and return play an important role in diversification within an internationalisation framework.

This paper is primarily concerned with operational risk, specifically with the risk associated with international expansion. We postulate that wealth-maximizing entrepreneurs will try to select the method of internationalisation with the lowest risk while attempting to achieve the greatest level of return; this suggests that risk– return trade-offs play a role in how SMEs internationalise.

Risk–return reward behaviour has been studied extensively in various literatures, such as those dealing with economics and finance. Research into entrepreneurial risk behaviour is inconsistent according to Das and Teng [18]. In 1952, Roy [28] presented his safety-first theory, which suggested that investors attempt to minimize the probability of ruin or failure. Provided that entrepreneurs and financiers are wealth maximizing, they would choose the method of internationalisation that minimizes risk while maximizing return. Markowitz [29] argues that investors should maximize the discounted value of future returns. Markowitz’s argument goes as follows. Suppose an entrepreneur decides to expand into two countries. Theoretically, if the two countries present equal risks, internationalizing the company’s operation in both countries at the same time results in lower risk. Markowitz also argued that this principle applied to investor rather than speculative behaviour. While Markowitz developed his theory to deal with constructing an optimal portfolio of securities, Lopes [30] developed a psychological theory of choice under uncertainty specifically applicable to choices that affect personal wealth. Lopes [30] refers to her theory as the SP/A theory where ‘S’ stands for security, ‘P’ for potential, and ‘A’ for aspiration. Lopes’s definition of security is similar to that of Roy [28]. Shefrin and Statman [31] refer to Lopes’s security definition as a general concern about avoiding low levels of wealth. In our case, we refer to security as the degree of wealth or level of poverty that describes the value of the firm. In a discrete sense, we can think of a firm as having a high or low value. ‘Aspiration’ refers to a goal and ‘potential’ refers to the goal of achieving high levels of wealth [31]. These variables may take on different values, but it is reasonable to expect either a high or a low value. In Lopes’ framework, fear affects the attitude toward a risky outcome and hope affects the individual’s disposition toward potential. Risky outcomes are evaluated using two variables. The first variable is the expected value of wealth, and the second variable is the probability that a certain payoff will be larger than other alternatives.

Shefrin and Statman [31] have developed a behavioural portfolio theory (BPT), similar to that of Markowitz [29] and Roy [28]), built upon Lopes’s [30] framework. According to BPT, most entrepreneurs want to avoid failure while increasing firm value. This suggests that they want to avoid poverty and therefore avoid expansion that results in failure. As a result, the theory suggests that entrepreneurs will make decisions that minimize the risk associated with international expansion for a given level of return by taking offsetting positions. We argue that SMEs expanding into two or more countries are taking offsetting positions. Expanding into one country may help in achieving limited aspirations but does not necessarily help the entrepreneur avoid poverty; failure in one country may leave the entrepreneur in considerable difficulty. Expansion into only one country may not allow entrepreneurs to achieve high aspirations within the customary time frame assigned by venture capitalists. Firms financed by venture capital may therefore exhibit a greater propensity to expand into several countries simultaneously. This argument is consistent with the findings of Keh, Foo, and Lim [32], who argue that entrepreneurs feel able to influence future outcomes and may take appropriate actions to hedge risks. Our argument is equally applicable to investors, and we will now discuss how this framework fits into modern portfolio theory (MPT). The main difference between BPT and MPT relates to correlation and covariance: covariances are not explicitly taken into account in BPT, while they are integral to MPT.

Modern portfolio theory suggests that entrepreneurs will select a set of options that maximizes returns for a given level of risk. The presence of risk means that the entrepreneur cannot associate a payoff with making a single investment decision. Instead, the payoff must be described as a set of outcomes and their probability of occurrence. If the returns from investing in internationalisation in each of several countries are not entirely correlated, then significant risk reduction will be achieved through diversification. Expansion into several countries may thus be a vehicle for diversifying. The characteristics of the return from internationalizing into several countries can also differ from that of a single-country investment. In summary, we argue, along with Shefrin and Statman [31], that MPT and BPT are complementary and that both are applicable in the case of SME international expansion.

International expansion is a major risk since it involves scarce human and technical resources, time, opportunity costs, and capital. Rapid expansion is dangerous and involves substantial increases in the number of employees, including management resources [1]. It follows that one way to minimize risk while maximizing wealth is to use a diversified global approach. A global approach means that the entrepreneur would internationalise into several regions, expecting that expansion into certain countries would be more successful than expansion into others. We will now discuss our model.

The opportunistic portfolio model (OPM) describes how firms internationalise using a multi- country approach. We refer to this as the global approach, consistent with the terminology of Chetty and Campbell-Hunt [1]. An important difference from the stage models is that OPM explicitly takes into account risk and return. Network models are not consistent across the literature with respect to risk and return, since network models view risk implicitly, e.g. [8] by assuming that a network provides protection against risky internationalisation. The opportunistic portfolio model tolerates isolated failures since it views internationalisation as a portfolio of opportunities. Risks are minimized by the multi-country approach, where the failure of expansion into a single country is offset by success in other countries. It is of course possible to achieve a mixture of both success and failure in each country, but what we are looking at is net success. Our approach is consistent with that of Chetty and Campbell-Hunt [1], who argue that manufacturing firms select either a narrow regional approach or a global approach depending on the overall strategy configuration.

In summary, methods of internationalisation have been studied extensively. Existing research is primarily based on foreign direct investment theory, the stage model, and the network model. The results are generally mixed; the support found for the latter two models under various circumstances suggests a more complex pattern than expected. We argue that risk and wealth maximization are important to SMEs when they decide to internationalise their operations. We will now discuss an exploratory hypothesis, which is being used to refer to a research hypothesis in an early stage of development. We are not testing hypotheses in a traditional sense.

Hypothesis

Our theory suggests that entrepreneurs attempt to maximize returns while controlling risk through a portfolio approach. In the context of internationalisation, entrepreneurs select an approach that ensures the maximum likelihood of success while minimizing risk. We hypothesize that firms using an opportunistic portfolio model of internationalisation are more likely to succeed in their efforts to internationalise, within a specific time frame, than are firms using either the stage or a combined model. Risks are explicitly minimized, since with a multi-country approach, the failure of expansion into one country is offset by success in another. Our measure of success, as previously stated, is international sales as a percentage of total sales in one-year increments. We also take into account how many countries the firms have entered successfully.

Methodology and Sample

International entrepreneurship research has been criticized for lacking a uniform approach and a clear theoretical and methodological direction [15]. This study attempts to remedy problems encountered in the existing literature. To address the issue of uniformity we use a more homogeneous sample, as described below in the section entitled ‘Sample’. We also use a research methodology suitable for small data sets and attempt to address the inconclusive results found in many studies that examined large data sets.

To address theoretical and methodological concerns, we are following the suggestion of Low and MacMillan [33] by incorporating an evolutionary approach and developing a theory of internationalisation that considers the context in which the internationalisation takes place. As suggested by Coviello and McAuley [5], we used multiple methods of data collection and analysis. This is described more fully in the section entitled ‘Methodology’.

Sample

We employed the following guidelines to obtain a sample consistent with our research objectives. First, the companies studied must have sales of € 100,000 to € 10 million. One firm depended entirely on the food industry for its revenue, two firms did not derive any revenue from the chemical sector and the remaining three firms derived a substantial portion of their revenue from large petrochemical, pharmaceuticals, bulk and speciality chemicals and pulp and paper firms. Second, the companies also had to be in the initial phases of internationalisation, so the authors could observe the entire process from the beginning. Third, firms were selected from the Nordic region (a narrow geographic focus is consistent with the practise found in the existing literature). Fourth, only business-to-business (B2B) software firms were selected so as to achieve homogeneity of business and revenue models among the sampled companies. Excluding business-to-consumer (B2C) firms improved the sample compared with those of previous studies since a number of factors such as length of sales cycle and revenue models differ significantly between these two groups. Fifth, only those software firms with complex products were included. We argue that software firms are good proxies for other firms with complex products, such as food, chemical, and pharmaceutical companies, because software development is subject to a number of complexities, including the development process itself, implementation, and post-implementation service and upgrading. Sixth, firm size, as measured by sales, was kept as uniform as possible to prevent atypically large private or public firms from skewing the results. While uniformity in the size of the firms was important, their size as measured in terms of revenue did differ. Seventh, company funding by means of venture capital was consistent across the sample, although the level and characteristics of this funding differed. Significant venture funding helped minimize the impact of resource constraints on the process of internationalisation.

Total sample size was six firms in Sweden, Norway, and Finland. Data were collected by observation, interviews, questionnaires, meetings, and examination of written internal and publicly available material. A total of 18 interviews and multiple questionnaires were completed for each firm over a two-year period. In all, the research lasted from 1996 to 2001. Multiple-item measures and multiple respondents were used to enhance internal consistency [34], an approach that obtains more complete information [35].

Methodology

This study was a multi-company, longitudinal case study. Chandler and Lyon [36] suggested that future entrepreneurship research incorporate longitudinal research to a greater extent. The research methodology is largely based on Schein [37][38] and Mårtenson [34]. Schein [38] argues that gathering data from natural situations is important. He defines clinical research as the observation, elicitation, and reporting of data that are available when actively studying an organization in its natural setting. Clinical research is an extension of active research, the main difference being that the researcher enters the situation in response to the needs of the organization, not the researchers’ need to gather data [38]. The result is that the object of the study does not feel under investigation, since the research is unobtrusive. This study is an example of clinical rather than action research because one of the authors was providing advice to the firms, enabling a non-obtrusive approach. Benbasat [39] defines case study as the examination of a phenomenon in its natural setting, employing multiple methods of data collection to obtain information. Yin [40] states that a case study is suitable for studying an event over which the researcher has little or no control.

Kimberly [41] defines longitudinal research as those techniques, methodologies, and activities that allow the observation and description of organizational phenomena. The obvious question in longitudinal research is how long the study should last. The existing literature supports the notion of both single- and multi-period studies depending on what is being examined. A multi- period approach was deemed appropriate here since the authors were interested in observing changes in ongoing processes.

The results from the data collection were analysed primarily by using data triangulation, triangulation being defined as comparing different types of information [34]. The goal of triangulation is not to determine the objective truth, but to add breadth and scope to the analysis. Coviello and McAuley [5] have suggested that triangulated research methodologies offer a better opportunity to capture complex issues involved in internationalisation. Mårtensson [34] regards ‘triangulation as means of alternative interpretation rather than a search for absolute truths. The results are analysed through a process of interpretation based on empirical sources, empirical material, and empirical description followed by conclusions’. In this study, the authors investigate phenomena and events over time and as they occur in different cases. The term ‘analysis’ as used in this paper refers to an iterative process that follows this approach.

Findings and Discussion

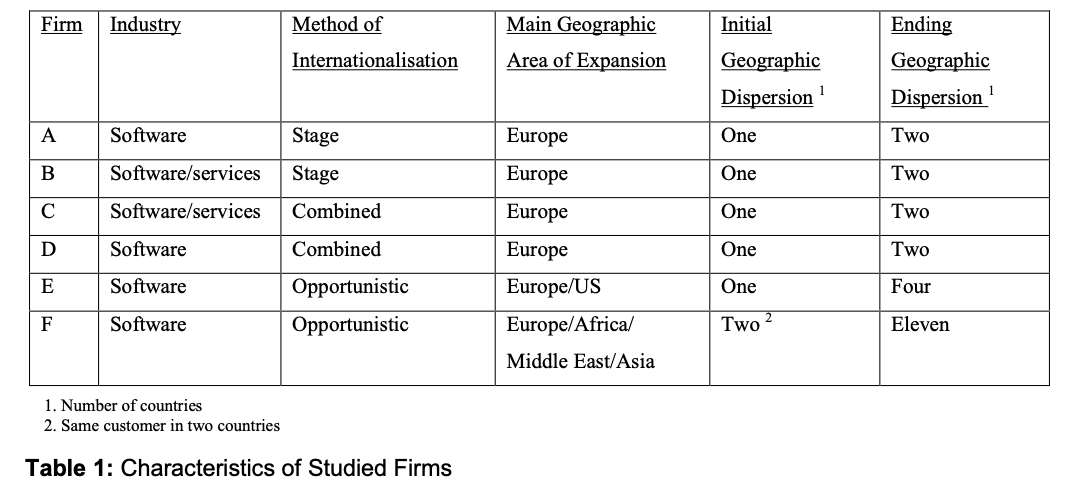

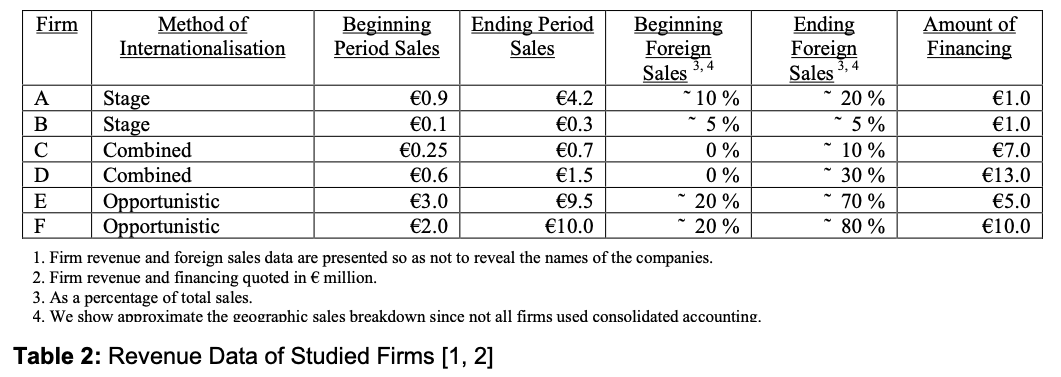

To address the research question articulated previously, we will present our findings and discuss the internationalisation process of each company. Then we will compare three of the sampled firms: A, E, and F. The firms in the sample are divided according to their method of internationalisation; tables I and II show characteristics of the sampled firms.

Firms A and B used a classic stage approach in their efforts to internationalise. Firms C and D utilized an opportunistic portfolio approach combined with elements of a traditional stage or network model, while firms E and F used an opportunistic portfolio approach. To establish the reliability of the results, the authors analysed the details of each firm’s business, including regulatory filings such as board reports and financial statements. Based on interviews with management, all firms except firm E used business risk analysis in their efforts to internationalise; this was especially pronounced in firms A, C, and F. Firm E did take technology risk into account but did not consider other business risks in their decision- making framework. While firms B and D took risk into account, this was not formalized within their respective decision-making frameworks to the same extent as in firms A, C, and F. None of the firms relied on partners or joint ventures to any great extent, reflecting the general belief of management that product and market complexities made transfer of knowledge to partners costly.

The overall results of the study support the opportunistic portfolio model. Firms using an extremely aggressive opportunistic approach were more successful than firms using a stage or combined approach. Similar to Bell [42] and Coviello and Munro [8], we found that the network model had some merit, although we found less support for this than did previous studies. It is important to note that all firms operated in highly volatile markets characterized by rapid growth and technological change. Therefore, it was perhaps not unreasonable for the firms to take risk into account.

The level of success appeared to depend on the level of aggressiveness combined with formal risk assessment, since firms using the combined approach tended be to less successful than firms using an opportunistic approach. Initially it appeared that a size effect, as defined by annual revenue, was present, since the two most successful firms were the two largest. Closer inspection of the firms showed that, using European GAAP, one of the large firms recognized research and development as a revenue item, which accounted for approximately 40% of total revenue. This suggests that while size may be a factor, it does not appear to be as significant as the authors had previously thought. Initially, all firms in the sample had less than €3,000,000 in revenue.

Resource constraints were minimised since all firms had significant venture capital funding; resource constraints were not eliminated since the authors observed personal, management, and board preferences in imposing artificial resource constraints on the firms’ operations. Based on the judgement of the authors, firm E also appeared to have more resource constraints than did the other firms in the sample. We will now discuss the results in detail. Please recall that all of the firms were characterized as successful during the time frame of the study.

Firm A used a classic stage approach. Initially, the company expanded sequentially into each Scandinavian country followed by Luxembourg and Switzerland. Interestingly, the company obtained a customer in Germany but did not formally attempt to enter this market, supporting our argument that the firm did not consider expanding opportunistically. The firm conducted thorough marketing research using third-party vendors, as evidenced by presentations made in management meetings and to the board. The company implemented a policy of pre-screening sales prospects and generally did not follow up sales leads that did not meet the pre-determined criteria. Sales efforts were generally planned in advance, although the company made some effort to accommodate firms that were deemed interesting. So the opportunistic sales target would be removed. Firm A established two foreign subsidiaries during the time frame of the study.

In the Nordic region, the firm achieved some success using the stage method but was unsuccessful in generating revenue from its pan- European efforts. The researchers did not note any obvious confounding factors upon closer inspection of the organizational structure, clients, products, and competitors. The products were well received, as evidenced by the growth in the sophisticated Scandinavian markets. The client list was substantial with a number of well-known brand-name clients. The competitive landscape was deemed reasonable from the authors’ perspective: the European market space was served by 10 to 15 companies, the largest of which had sales of approximately €80 million. Resources were not a constraining factor, and firm operations were highly structured in comparison to other firms in the sample. We will discuss this issue later in the paper.

Firm B also used a classic stage approach, but for several reasons achieved only limited success in its internationalisation efforts. First, firm B did not have a solid domestic revenue base, which could potentially have reduced its credibility with international customers. No foreign subsidiary was established during the period of study. Under- investing in the process of internationalisation did not appear to be the problem. The firm did have fewer managers than did the other sampled firms, but this seemed appropriate, given that the firm was the smallest in the sample. At the same time, the authors did not notice any tangible differences in the quality of management, though we did not study this factor extensively. Faulty or incomplete execution of the stage model did not appear to be the problem. The company used external marketing data in its decision-making processes, used appropriate marketing tools, and had a product that appeared competitive. The competitive landscape was favourable with three pan-European competitors. There were additional local competitors, but none that the authors encountered had a dominant market position.

Firm C had an established customer base in its domestic market where it was ranked as the number one supplier. Firm C used a combined stage and opportunistic approach in expanding outside its domestic market. The stage model was used primarily in Scandinavia, while the opportunistic portfolio approach served as the platform for expansion into Europe. Within Europe, the company focused its efforts in the Germanic-speaking and Mediterranean regions. The stage model was largely ineffective in expanding within Scandinavia, as the company did not receive any orders within the time frame of the study. The European expansion efforts resulted in a single large contract within 12 months of initiating expansion, and as a consequence, one foreign subsidiary was created. The firm used a moderately aggressive approach in its efforts to internationalise. We further analysed the potential reasons for management’s perceived lack of success in European and, especially, Scandinavian markets. It became evident that certain parts of the organization had not been prepared for the internationalisation, suggesting mental and physical under-investment. A common theme in informal discussions with the firm’s middle management was a perception that it was unnecessary to expand outside the Nordic markets because major opportunities were available there. Also, senior management believed that the sales cycles were unrealistically short, further supporting under- investment in specific sales leads and client projects. In discussing the firm’s strategic efforts, we noted that the firm had resource constraints in the technical area, which resulted in technical development being diverted to domestic customers compared to potential customers in non-domestic markets. While this may have had an effect, we feel that the European customer would not have purchased the product if it was internationally non-competitive or if there were significant development issues in bringing the product up to a satisfactory standard. Nevertheless, technical resource constraints may have played a role. In addition, one country- specific market collapsed during the time frame of the study. It is also important to note that the period of study corresponded to a downturn in the specific market space served by Firm C, and this may have affected the results it obtained.

Firm D provided some interesting insights into the process of internationalisation. All owners were active managers in the company. The company had ample funding available to strengthen management, technology, and sales. Prior to the study period, the firm established itself as one of the top two domestic companies in its field before initiating internationalisation efforts. After doing formal market research, the company embarked on expansion efforts using a combined stage approach within Scandinavia, and network and opportunistic approaches in Europe. In Europe, the company started two subsidiaries, including one in the UK which pursued a network- based approach. In continental Europe, the firm used an opportunistic approach. The combined approach resulted in significant revenue in a second Scandinavian country, as well as in two continental European countries, but not in the UK. During the period of the study, Firm D did not achieve any revenue in the UK. The authors noted that firm D consistently under priced its products relative to those of its competitors in order to gain access to international markets. This strategy was also conspicuously used by the other firms in the sample, but not on a consistent basis. It could indicate that firm D’s market space was highly competitive or that its product was inferior. In discussions with senior management, it became evident that personal preferences played a role in locating an office in the UK. Management perceived the UK market to be difficult, but believed that this would be mitigated by strong networks of large local and global consulting firms. The company also faced significantly greater competitive pressures in the UK market compared to other markets in Europe and Scandinavia. The authors also noted a lack of product focus and an overall lack of focus in the company.

Firm E used an extremely aggressive opportunistic portfolio approach in its efforts to internationalise and was able to develop markets in Scandinavia, Spain, the UK, Germany, and the USA. During the observation period, the firm established three foreign subsidiaries. The firm used a highly unstructured and opportunistic approach with little formal follow-up of its market and sales activities, unless there was a personal interest on the part of the owners. The company did not produce formal plans for its internationalisation, nor did it try to localise its products before entering a new market. Interestingly, compared to Firm F, the company did not have a solid domestic revenue base. While the initial customer was domestic, all subsequent customers within the time frame of the study were non-domestic. In firm E, the owners were heavily involved in the day-to-day operation in sales, marketing, and product development. Since the company had not standardized its products, a significant amount of human and financial resources went into software development. The company therefore had some financial resource constraints, and had under-invested in certain areas of its expansion efforts, including administration, professional management, product development, and internationalisation. The efforts to internationalise were characterized by ‘lumpiness’, which refers to both a lack of consistency in decision-making that affects the company’s rate of expansion, and a lack of follow- up to its sales and marketing activities. While technology risks were explicitly taken into account, other business risks were not explicitly considered within the decision framework.

Firm F also used an extremely aggressive opportunistic approach in its efforts to internationalise. Firm F initially obtained four domestic customers, which were internationally well-known and could serve as reference customers. One of the customers implemented firm F’s product in two locations in Scandinavia, perhaps providing the initial impetus to internationalise. This lends some support to network theory. The owners were involved in the day-to-day running of the firm, mostly working on technology-related issues, but also active in strategy development and in the strategic marketing of the firm’s products. The firm hired a salesperson of international calibre when it had six employees. Some initial research was performed before marketing the products in each country, although this primarily focused on regulatory aspects, which differed substantially from country to country. Initially, no other person was involved in the efforts to internationalise, except in the technical support capacity in the domestic office. The internationalisation efforts were consistently very aggressive and opportunistic, and the company initially marketed its products in Europe, the Middle East, South Africa, and certain parts of Asia. While the company did not especially want to sell its products in the USA, it nevertheless participated in US trade shows and opportunistically visited potential North American customers. Sales meetings were scheduled without qualifying the sales leads. When sales suspects became prospects, the company became very formal in the process leading up to the signing of the contract, but still maintained significant flexibility to accommodate different styles on the part of the sales prospect. This was in great contrast to the initial sales process, which was extremely flexible from the company’s point of view.

Firm F generated revenue in Scandinavia, Switzerland, the UK, Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium, and in countries outside Europe (South Africa, two countries in the Middle East, and one in Asia) within the time frame of the study. Five international subsidiaries were established during this time. Attending management and board meetings and holding discussions with senior management revealed that the company deliberately pursued an opportunistic strategy. The main reason given was that the sales cycles were lengthy and that many variables affected the sales process, most of which were beyond the control of the company. In addition, the owners of the company stated that the company’s value would be enhanced by showing that the firm’s products were suitable for various international markets. This was verified by the authors in discussions with two investment banks.

In comparing firms E and F, several differences emerged. First, firm F had better capital. Second, while both firms used an opportunistic approach in their initial sales and marketing efforts, firm F used a more structured approach to following these up, resulting in less lumpiness compared to Firm E. Both firms suffered from lack of management depth, and focused on acquiring technical and sales personnel during the period of study. Increasing management capacity and skill level was explicitly considered secondary by the firms, although the authors noted that firm F strengthened its management during the time of study; firm E, by contrast, made no efforts either to develop its management ranks or to increase the functional skills of existing management. Finally, firm E’s products required less local adaptation than did those of firm F.

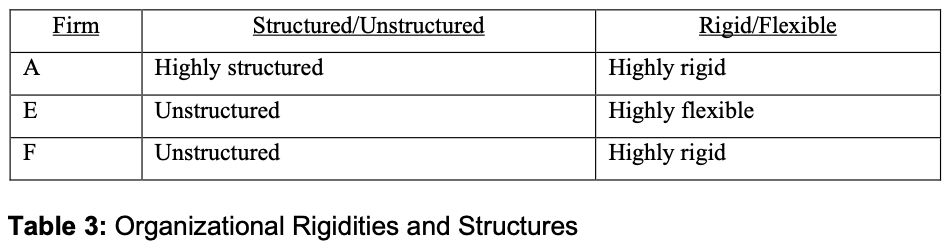

In our research, we noted that the degree of organizational rigidity differed among firms and appeared related to the degree of success. We conducted additional analysis of our data that is not related to our research hypothesis. Firms A, E, and F offered us unique opportunities because the target customers of these firms were the same, although sales efforts did not necessarily target the same departments. This analysis was undertaken in order to discern whether level of flexibility affected the success or failure of efforts to internationalise. Tienari and Tainio [43] maintain that firms exhibiting organizational rigidities are less able to cope with volatile environments, such as those encountered by internationalizing firms. All three firms exhibited differences with respect to organizational rigidities and structures. Table IV shows how the firms differed in these respects.

Firm A generally used a highly inflexible and highly structured approach to conducting business. Its sales and marketing processes followed a pre- determined rigid approach and once a customer was acquired, a highly structured approach implemented the product and dealt with customers. Firm E used a highly flexible and highly unstructured approach. Firm E used a highly opportunistic approach in acquiring customers, but had very little structure in dealing with implementation issues and customers in general. Firm F was classified as highly flexible and structured. It used a highly opportunistic approach to customer acquisition and a highly structured approach in product implementation and customer relations . In addition, Firm F, like Firm A, had a significant domestic customer base; Firm E did not have a large domestic revenue base.

Of the three firms, Firm A was the least successful in internationalizing within the time frame of the study. The firm had at least three possibilities of acquiring foreign customers during the two-year period, but chose not to do so mainly because of its organizational structure and rigidities. The firm focused on activities that fit its pre-programmed approach to internationalisation rather than focusing on acquiring customers. Firm E acquired several international customers, but was generally unable to capitalize significantly on these opportunities. An unstructured approach prevented it from expanding its customer revenue effectively, while its highly flexible approach prevented it from focusing.

Firm F also acquired several international customers. Its primary method of acquiring international customers was initially unstructured, but was generally followed by a structured and highly rigid post-acquisition approach in maintaining and enhancing its customer relationships. Although this analysis is limited in scope, the results indicate that organizational flexibility and level of structure affect internationalisation success for firms with long sales cycles and complex products.

The implications of this study are that software firms with complex products do not use networks and partnerships to a large extent in their efforts to internationalise. The most successful firms used an opportunistic approach to customer acquisition, while following a structured approach in dealing with customers during the post-acquisition period. In addition, firms that operate in volatile markets, experience rapid growth, and encounter rapid technological changes appear to take risk explicitly into account in their efforts to internationalise.

Summary and Conclusions

The purpose of this longitudinal clinical case research was to further our understanding of how firms internationalise their operations. To achieve the aim, we studied six Nordic software firms, each of which had a complex software product to sell to other businesses. Our findings suggest that there are other factors in addition to those presented in existing stage- and network-based research. Specifically, we found that integrating risk and return issues further develops the theory of how SMEs internationalise, and that integrating network models into an explicit risk and return framework enhances our understanding of the decision-making processes of internationalisation. Our findings are consistent with those of Chetty and Cambell-Hunt [1], as we found that global firms that use an opportunistic portfolio approach appear more successful in their internationalisation efforts.

Three important contributions of this paper relate to the sample selection, the choice of methodology, and further theory development. In addition, the study focused on the process of international expansion using a risk and return framework. Our research builds on Chetty and Campbell-Hunt [1] by analysing success in the internationalisation efforts of small Nordic software firms with complex products. We found weak support for Coviello and Munro’s [8] conclusions that networks play a role in international expansion.

There are several important findings of this study. First, it provides further evidence that the stage model is insufficient to explain how firms expand internationally. Second, contrary to Coviello and Munro [8], we found weak support for the operation of the network model in the development of market-development activities. Coviello and Munro [8] studied four software firms in New Zealand, where it is possible that transaction cost issues and the distance to major markets necessitated a network approach. While our research found some support for the utility of small software firms making simultaneous use of multiple and different modes of entry, firms using an opportunistic approach tended to be more successful than firms using either a classical stage approach, a network approach, or a combined approach. We found preliminary indications that use of an opportunistic or diversified approach in the initial phases of internationalisation followed by significant structure in organizational processes enhanced success. Third, risk and return was taken into account by most of the firms; we found support for the risk framework presented by Lopes [30]. Fourth, sample selection, the choice of clinical research methodology, and the use of an interpretative approach represent additional contributions. Data access is always a difficult area in gathering non-public information, and many traditional models are not suitable in these cases.

There are several implications for chemical and pharmaceutical firms. It is evident from this research that the stage or network approach is sub- optimal in gaining a significant presence in international markets. This may be especially true for firms dealing with complex products where sales cycles may be lengthy. A single country expansion may also be sub-optimal in cases where “natural” multi-country groupings occur. This does not mean that single country expansion is obsolete at all times. South America provides a good example: Brazil may be a single country expansion since it is linguistically or culturally somewhat different from some of other South American countries. Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Paraguay form a multi-group expansion opportunity, however. This leads us to the most important implication. Risk assessment should always play a role in international expansion. Risk is mitigated by looking at international expansion as a portfolio of opportunities. A portfolio of opportunities allows firms to expand into several countries in an opportunistic fashion. Earlier in the paper, we spoke about the German speaking part of Europe. An expansion into this region using an opportunistic approach makes it more likely that the firm will succeed, ceteris paribus, since the risk of not gaining a market foothold is spread across three or four countries. Using a staged approach, failure to gain a foothold is costly both in time and money because it would require the firm to begin expansion into a second country after failing in the first.

In this study, we are primarily reporting on software companies that sell and market their products to food, chemical and pharmaceutical firms. However, we believe that our conclusions can be generalized to all firms with complex products, especially food, chemical, and pharmaceutical firms that are attempting to expand internationally.

There are several limitations associated with clinical research. First, clinical research and an interpretative approach often do not examine the external conditions that give rise to certain meanings and experiences [34]. Although care was taken to analyse confounding variables and aspects, it is possible that these affected the results of this study. Second, the results are difficult to generalize until other researchers have performed similar analyses using different-sized samples across different countries over time. This is important, not only to validate the results, but also as a step toward formulating testable hypotheses and theories that apply across settings [44]. Finally, the interpretative approach is subjective and two researchers may not interpret the findings the same way.

Our study opens up a set of opportunities for researchers willing to commit time and resources to the in-depth exploration of factors and processes affecting efforts to internationalise. These include studies across samples in different countries. In-depth analysis of other factors affecting success in internationalisation is also needed. Applying the clinical research and interpretative methodologies to different settings and variables would also be fruitful. The results of this study also indicate that researchers may also want to look at contingency variables. How organisational rigidities affect internationalisation appears to be an interesting area of further research.

References

[1] Chetty, S. and Campbell-Hunt, C. 2003. Paths to internationalisation among small- to medium-sized firms: a global versus regional approach, European Journal of Marketing, 37 (5/6): 796–820.

[2] Wright, W. and Ricks, A. 1994. Trends in international business research: twenty-five years later, Journal of International Business Studies, 25 (4): 687–701.

[3] Autio, E., Sapienza, H. J. and Almeida, J. G. 2000 Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity and imitability on international growth, Academy of Management Journal, 43 (5): 909–924.

[4] Johanson J. and Wiedersheim-Paul, F. 1975. The internationalisation of the firm—four Swedish cases, Journal of Management Studies, 12: 305–322.

[5] Coviello, N. and McAuley, A. 1999. Internationalisation and the small firm: a review of contemporary empirical research, Management International Review, 39 (3): 223–256.

[6] Gankema, H., Snuif, H. and Zwart, P. 2000. The internationalisation process of small and medium-sized enterprises: an evaluation of stage theory, Journal of Small Business Management, 38 (4): 15–27.

[7] Bell, J. 1995. The internationalisation of small computer software firms—A Further Challenge to ‘Stage Theories’, European Journal of Marketing, 29 (8): 60–75.

[8] Coviello, N. and Munro, H. 1997. Network relationships and the internationalisation process of small software firms, International Business Review, 6 (2): 361–386.

[9] Lu, J. and Beamish, P. 2001. The internationalisation and performance of smes, Strategic Management Journal, 22 (6/7): 565–586.

[10] Yip, G., Biscarri, J. and Monti, J. 2000. The role of internationalisation process in the performance of newly internationalised firms, Journal of International Marketing, 8 (3): 10–35.

[11] Apfelthaler, G. 2000 Why small enterprises invest abroad: the case of four Austrian firms with U.S. operations, Journal of Small Business Management, 38 (3): 92–98.

[12] Anderson, S. 2000 The internationalisation of the firm from an entrepreneurial perspective, International Studies of Management and Organization, 30 (1): 63–92.

[13] Coviello, N. and Martin, K. 1999. Internationalisation of service smes: an integrated perspective from the engineering consulting sector, Journal of International Marketing, 7 (4): 42–66.

[14] Jones, M. 1999. The internationalisation of small high-technology firms, Journal of International Marketing, 7 (4): 15–41.

[15] McDougall, P. and Oviatt, B. 2000. International entrepreneurship: the intersection of tworesearchpaths,AcademyofManagement Journal, 43 (5): 902–906.

[16] Crick, D. and Jones, M. 2000. Small technology firms and international high-technology markets, Journal of International Marketing, 8 (2): 63–85.

[17] Westhead, P., Wright, M., Ucbasaran, D. and Martin, F. 2001. International market selection strategies of manufacturing and service firms, Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 13 (1): 1–34.

[18] Das, T. and Teng, B. 1997. Time and entrepreneurial risk behaviour, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22 (2): 69–88.

[19] Kaish, S. and Gilad, B. 1991. Characteristics of opportunities of entrepreneurs versus executives: sources, interests, general alertness, Journal of Business Venturing, 6 (1): 45–61.

[20] Palich, L. and Bagby, D. 1995. Using cognitive theory to explain entrepreneurial risk-taking: challenging conventional wisdom, Journal of Business Venturing, 10: 425–438.

[21] Sarasvathy, D., Simon, H. and Lave, L. 1998. Perceiving and managing risks: differences between entrepreneurs and bankers, Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organization, 33: 207–225.

[22] Forlani, D. and Mullins, J. 2000. Perceived risks and choices in entrepreneurs’ new venture decisions, Journal of Business Venturing, 15: 315– 322.

[23] Chicken, J. 1996. Risk (London, UK: International Thomson Business Press).

[24] Brunson, N. 2000. The Irrational Organization: Irrationality as a Basis for Organizational Action and Change (Bergen, Norway: Fagbokforlaget).

[25] Qian, G. 2002. Multinationality, product diversification and profitability of emerging us small- and medium-sized enterprises, Journal of Business Venturing, 17: 611–633.

[26] Rugman, A. 1976. Risk reduction by international diversification, Journal of International Business Studies, 7: 75–85.

[27] Kim, W ., Hwang, P . and Burgers, W . 1993. Multinationals’ diversification and the risk return trade-off, Strategic Management Journal, 14: 275–286.

[28] Roy, A. 1952. Safety-first and the holding of assets, Econometrica, 20: 431–449.

[29] Markowitz, H. 1952a. Portfolio selection, Journal of Finance, 6: 77–91.

[30] Lopes, L. 1987. Between hope and fear: the psychology of risk, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 20: 255–295.

[31] Shefrin, H. and Statman, M. 2000. Behavioral portfolio theory, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 35 (2): 127–151.

[32] Keh, H., Foo, M. and Lim, B. 2002. Opportunity evaluation under risky conditions: the cognitive processes of entrepreneurs, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27 (2): 125– 148.

[33] Low, M. and MacMillan, I. 1988. Entrepreneurship: past research and future challenges, JournalofManagement,14:139–161.

[34] Mårtensson, P. 2001. Management Processes: An Information Perspective on Managerial Work (Stockholm, Sweden: The Economics Research Institute).

[35] Ramirez,M.andEscuer,M.2001.Theeffectof international diversification strategy on the performance of spanish based firms during the period 1991 to 1995, Management International Review, 41 (3): 291–315.

[36] Chandler, G. and Lyon, D. 2001. Issues of research design and construct measurement in entrepreneurship research: the past decade, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25 (4): 101– 113.

[37] Schein, E. 1987. The Clinical Perspective in Fieldwork, Qualitative Research Method Series (Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications).

[38] Schein, E. 1991. Legitimating Clinical Research on the Study of Organizational Culture, MIT Working Paper Series, WP# 3288-91-BPS (Cambridge, MA: Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

[39] Benbasat, I., Goldstein, D. and Mead, M. 1987. The Case Research Study in Studies of Information Systems, MIS Quarterly, 23 (1): 369–386.

[40] Yin, R. 1994. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Applied Social Methods Research Series (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications).

[41] Kimberly, J. 1976. Issues in the design of longitudinal organizational research, Sociological Methods and Research, 4 (3): 321–347.

[42] Bell, D. 1995. A contextual uncertainty condition for behaviour under risk, Management Science, 41 (7): 1145–1150.

[43] Tienari, J. and Tainio, R. 1999. The myth of flexibility in organizational change, Scandinavian Journal of Management, 15: 351–384.

[44] Eisenhardt, K. 1989. Building of theories from case study research, Academy of Management Review, 14 (4): 532–550.