Critical challenges for SMEs in the UK chemical distribution industry

Abstract

The UK chemical distribution industry, despite its significant contribution to the economy and employment generation, remains largely unexplored with no academic research regarding small businesses and their success. This is the first study to investigate the challenges that SMEs operating in the specific industry are facing, arguing that only when a small business is able to cope with, adapt to and overcome these, can it be successful. Utilizing a survey strategy, qualitative data were collected from 118 SMEs, out of the 180 identified, generating a response rate of 65.5%. Regulatory compliance, supplier management, human capital and access to capital are identified as critical. Findings suggest that success is a multidimensional phenomenon where all contributing factors need to be taken into consideration and addressed simultaneously. This paper informs thinking in this field and provides guidelines to various stakeholders to improve strategy formulation and decision-making process in order to support chemical distribution SMEs.

1 Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are in the focus of political, business and management research (Amoros et al., 2013; Dobbs and Hamilton, 2007; Lussier and Halabi, 2014) stating their benefits such as being integral to contemporary economic and social regeneration, essential for the establishment of a solid industrial base and being a key driver for innovation and R&D and above all, a significant contributors to employment generation (Franco and Haase, 2010; European Union, 2015; Halabi and Lussier, 2010; McLarty et al., 2012; Simpson et al., 2012; Smallbone et al., 2010; Unger et al., 2011).

Despite their well-established importance, there is still no universally accepted definition for SMEs with significant variations in different countries (Smallbone et al., 2010; Unger et al., 2011), no single agreed-upon definition of success (Beaver, 2002; Rogoff et al., 2000), no universally accepted model to incorporate all aspects of small business success (Chawla et al., 2010; Dobbs and Hamilton, 2007; Lampadarios et al., in press). Most importantly, SMEs tend to exhibit high failure rates and poor performance levels (Arasti et al., 2012; Franco and Haase, 2009; Gray et al., 2012; Ropega, 2011) with their success and/or survival receiving an ever-increasing attention from academia and professionals alike.

The business literature features a wide range of success factors through a number of conceptual frameworks that attempt to capture aspects of SMEs success. However, their importance appears to be relative and varies with the business environment, that is the industry and country SMEs operate in; meaning that while one success factor may be of great importance in one industry or country, it may not necessarily be of equal importance in another (Benzing et al., 2009; Kader et al., 2009; Krasniqi et al., 2008; Lin, 2006; Ogundele, 2007; Simpson et al., 2012). This inevitably creates a need for more empirical studies to investigate all aspects of success and identify critical factors in each industry and in a specific country setting.

An industry where small businesses have a particularly strong presence is the European and particularly the UK chemical distribution (BCG, 2013; Chemagility, 2012; Districonsult, 2013; FECC, 2013). However, very little is known about SMEs in the specific industry, their modus operandi and any factors contributing to their success and/or failure (Chemagility, 2008; CBA, 2015; FECC, 2015). In fact, due to the wide variety of functions performed by these companies and confusion with other types of trading in the industry, there is still no universally agreed definition of a chemical distributor (Chemagility, 2012). Last but not least, there appears to be no official statistical and/or financial data available on SMEs operating in the UK chemical distribution industry (Chemagility, 2015).

Overall, this paper thus aims to identify and offer an insight into the challenges that SMEs in the UK chemical distribution industry are facing. Initially, SMEs, their importance, definition and characteristics are introduced, followed by an overview of the chemical distribution industry with particular focus on the UK. The rationale and methodology of this study are then elaborated on. Findings are presented and discussed offering concluding remarks and several implications for practice.

2 Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)

2.1 Importance of SMEs

The importance of SMEs and their contribution to the economy and employment generation has long been established in the business literature (Dobbs and Hamilton, 2007; Galapova and McKie 2012; Halabi and Lussier, 2014; Smallbone et al., 2010). In the European Union, micro, small and medium sized enterprises are socially and economically important as they represent 99% of all enterprises (European Union, 2015). They employ around 90m people, generate EUR 3.7tn in added value while providing 2 out of 3 jobs and contributing to entrepreneurship and innovation (European Union, 2015). In the UK, the Department for Business and Innovation (2014) reports that, at the start of 2014, small and medium-sized businesses employed 15.2m people and had a combined turnover of GPB 1.6tn; these accounted for 99.3% of all private sector businesses in the UK, 47.8% of private sector employment and 33.2% of private sector turnover. Due to the fact that SMEs are a major part in today’s modern economies, an understanding of why they succeed or fail is crucial to the stability and health of the economy and research is still needed in this field (Blackburn and Kovalainen, 2009; Holmes et al., 2010; Philip, 2011; Raju et al., 2011).

2.2 Definition of SMEs

Even though SMEs is an area well researched, there is still no universally accepted definition of what constitutes a small business with variations existing in different countries. For instance, in the United States, small businesses are defined as independent businesses comprising fewer than 500 employees and are further classified according to varying industry standards on employment size, sales and annual turnover (Office of the Advocacy United States Small Business Association, 2003). In Japan, SMEs are generally businesses which employ between 4 and 299 employees but yet again definitions vary according to both sector and capital invested. In the United Kingdom, the definition of SMEs is given through the UK Companies Act of 2006 which states that if a company is to be defined as ‘small’, it must satisfy at least two of the following criteria: (i) have a turnover of no more than GBP 6.5mn; (ii) have a balance sheet total of no more than GBP 3.26mn; (iii) have no more than 50 employees. Similarly, a medium-sized company must satisfy at least two of the following criteria: (i) have a turnover of no more than GBP 25.9mn; (ii) have a balance sheet total of no more than GBP 12.9mn; (iii) have no more than 250 employees.

In the European Union, any enterprise that employs fewer than 250 persons and has an annual turnover not exceeding EUR 50mn and/or an annual balance sheet total not exceeding EUR 43mn qualifies as a SME (European Union, 2015). Within the SME category, a small enterprise is defined as an enterprise which employs fewer than 50 staff and whose annual turnover and/or annual balance sheet total does not exceed EUR 10m while a microenterprise is defined as an enterprise which employs fewer than 10 persons and whose annual turnover and/or annual balance sheet total does not exceed EUR 2mn. For the purpose of this study, the definition of SMEs is that of the European Union.

2.3 Characteristics of SMEs

Overall, SMEs have several features that distinguish them from larger firms. Business literature concurs that their most important characteristics are the absence of complex formal structures, the dominance of owner/managers, the lack of internal labor markets, environmental uncertainty and a limited customer base (Adams et al., 2012; Floren, 2006; Storey and Greene, 2010). According to Simpson et al. (2012), the typical SME has limited resources, limited cash flows, few customers, is often engaged in management ‘fire-fighting’, concentrates on current performance rather than taking a strategic focus, often has a flat organizational structure and possibly high staff turnover. Similarly, a high risk of failure makes small businesses more focused on short-term survival than longterm planning and consequently ‘cash rather than profit’ (Adams et al., 2012; Raju et al., 2011).

Where perhaps SMEs are more distinct compared to larger firms, is the fact that they are defined very much by the personal commitment and motivation of their owners, which, in turn, creates with in firms an individual and particular approach to strategic management (Bonet et al., 2011; Raju et al., 2011; Perks, 2006). This means that, as organizations, they are likely to be sustained primarily by economically significant skills along with successive knowledge claims concerning the viability of those skills. In addition, their success is likely to be dependent on combining entrepreneurial orientation with strategic action (Hitt et al., 2001; Kumar et al., 2012). It is therefore recognized that the evolution of smaller firms is likely to be influenced by the development of firm-based resources and capabilities enacted through activity rather than the accrual of resources (Unger et al., 2011). To further support the absence of formality in small businesses, Rantanen (2001) in Forsman (2008) argues that small firms are more likely to engage in informal management practices than to adopt sophisticated planning and control techniques.

Adams et al. (2012), Forsman (2008) and Raju et al. (2011) provide a good account of small businesses advantages and disadvantages compared with large organizations. Advantages include the distinct flexibility that enables them to respond quickly to environmental changes, the informal management structure and centralized decision-making, the fact that they are close to the customers, and the ability to frequently use technology and/or superior quality to gain competitive advantage. The main disadvantages are the lack of formal strategy and formulation processes, which result in implicit rather than explicit business strategies, a focus on day-to-day problems instead of longer goals, the relative lack of resources (i.e. personnel, financial, and physical facilities), which discourages management specialization as multiple responsibilities are assigned to one person, and the relatively low degree of purchasing leverage (Adams et al., 2012; Forsman, 2008; Raju et al., 2011).

3 Chemical distribution and the role of SMEs

3.1 Overview on the chemical distribution industry

Chemical distribution companies are an integral part of the European chemical industry, positioned between chemical producers and their customers (FECC, 2015). Distributors are a vital, wellestablished sector of the chemical industry helping manufacturers accessing local customers and markets while adding value by reducing complexity, trade-related risks and costs and providing financing and support (BCG, 2010; Chemagility, 2008; Districonsult, 2009). Manufacturers rely on distributors to ensure the safe delivery of bulk and non-bulk chemicals to downstream end-users as well as to handle logistical needs of end-users, such as custom blending and non-bulk repackaging, which are operations not primary among manufacturing operations yet met by distributors (Chemagility, 2008; Hornke, 2012). Thus, chemical distribution fills the gap between producers who wish to sell large lots without regulatory or logistical complications and customers demanding small volumes and who have very specific needs on technical, regulatory and logistical level; in essence, chemical distributors allow their principals to profitably reach smaller customers in many industries and countries (Mortelmans and Reniers, 2012). Chemical companies increasingly realize the value of chemical distributors as value chain partners and implement structured distributor management functionalities in their organizations (CEFIC, 2012; Hornke, 2012). However, genuine chemical distributors, rather than simply selling chemicals, add value through an extensive range of services to both customers and suppliers (Hornke, 2012; Mortelmans and Reniers, 2012).

Despite the importance of chemical distributors, there seems to be no universally agreed definition of what a chemical distributor is. This is mainly because of the wide variety of functions they perform and confusion with other types of trading in the industry (Chemagility, 2008). However, chemical distributors have a number of distinct characteristics. According to the Health and Safety Executive, a distributor is any natural or legal person established within the community including a retailer, who only stores and places on the market a substance, on its own or in a preparation for third parties (Health and Safety Executive, 2015). Generally, chemical distributors buy and sell chemicals from producers taking title to the goods, responsibility for stocking and warehousing before selling the products on to their customers under their own brand (Chemagility, 2008; Districonsult, 2009; NACD, 2005). There is often a formal, longterm agreement between the distributor and the chemical manufacturer whom they represent (Chemagility, 2008). Chemical distributors need to be differentiated from mere logistics companies that typically do not take ownership of products and from trading companies that typically do not repackage and assemble product portfolios according to customer needs (BCG, 2010). Also, a distributor is neither an agent nor a chemical trader; these do not take title to or stock goods, but receive a commission for their contribution in helping a manufacturer complete a sale (Chemagility, 2008; NACD, 2005).

Chemical distributors offer a wide range of services to both customers and suppliers. The typical offering to customers incorporates a broad product portfolio with complementary products; access to reputable suppliers; competitive (and stable) pricing; stock management and Just In Time (JIT) deliveries; competent and knowledgeable sales team; technical support and problem solving skills; product expertise for formulation purposes; valueadded services, for instance, custom blending, repackaging); sample management; financing and credit in line with local terms; safety training and hazardous waste removal (BCG, 2013; Burns, 2010; Chemagility, 2008 and 2015; Chemanager, 2013; Districonsult, 2009 and 2012; FECC, 2013; Hornke, 2012; Jung et al., 2014; Mortelmans and Reniers, 2012; NACD, 2005). Equally, their offering to suppliers includes services such as market share and penetration; logistics services including storage and packaging; in-depth market intelligence and assist with the implementation of marketing strategies; demand forecasting and planning; market development capabilities; new product approvals; conforming to local regulations and language; repackaging and relabeling; arrangement of import authorizations; trainable staff with good technical knowledge; modern IT infrastructure allowing automated information exchange (BCG, 2013; Burns, 2010; Chemagility, 2008; Chemanager, 2013; Districonsult, 2012; FECC, 2013; Hornke, 2012; Jung et al., 2014; Mortelmans and Reniers, 2012; NACD, 2005).

Chemical distributors form a fragmented network and it is estimated that there are about 10,000 distributors, servicing the end users for their chemical needs (Brenntag, 2010; Boston Consulting Group, 2013). Chemical distributors are often small and medium enterprises with local and regional coverage (Bee and Chelliah, 2013; Brenntag, 2010; Chemagility, 2008). According to the European Federation of Chemical distributors (FECC), FECC members mainly SMEs create value in the chemical supply chain by meeting the demands of over 1m downstream users who are diverse regarding needs and purchase volumes. About 9-10% of the overall output of chemical producers is distributed via independent chemical distributors. In fact, the FECC represents over 1,700 companies with over 31,000 employees at more than 1,400 sites handling six million shipments and 31mn tons shipped with an industry turnover of EUR 27bn every year (FECC, 2015). This means that there is a wide variety of organizations involved in the distribution along the value chain between chemical producing companies and the industries using chemicals. Therefore, the chemical distribution industry does not only include chemical manufacturers and their distributors, but also chemical traders, agents, export/import houses and a number of other suppliers providing these companies with added value products or services, e.g. warehousing, logistics, plant and equipment (Chemical Business Association, 2015; CEFIC, 2012). Overall, it is evident that SMEs have a strong presence in the chemical distribution industry and play an important role in its overall growth and performance (CEFIC, 2012; FECC, 2013).

3.2 The UK chemical distribution industry

Chemical distributors are an integral part of the UK chemical industry (CBA, 2015; Chemagility, 2008; FECC, 2013). Even though chemical distribution is a well-established practice in the UK, it is severely understudied both on an academic and business level with the majority of information originating from the study of the European chemical distribution industry (Burns, 2010; Chemagility, 2008; Districonsult, 2009, 2011 and 2012; Jung et al., 2014; Hornke, 2013). Similarly, there are limited statistical data available on the industry and information such as turnover, sales and margin growth, performance and future trends are drawn from the Chemagility (2008 and 2015) and Plimsoll (2013) reports.

Plimsoll (2013) reports that an average company in the UK chemical distribution industry increased sales by 6.4% in 2012. However, the larger companies grew by 8.5%, compared to the smaller companies who grew by 1.9%, meaning that SMEs are not growing as fast. As such, research in the area of small business growth and specifically in success factors seems to be necessary.

According to the latest data available from Chemagility, the UK chemical distribution market was worth GBP 4.42bn (EUR 5.44bn) in 2014, employing circa 6,800 employees and representing 10% of the total European chemical distribution market worth EUR 52bn. The total number of chemical distributors in the UK was 280 and with over 75% of them being small or micro-sized enterprises (210 companies if subsidiaries of larger international groups are excluded), it is evident that SMEs have a very strong presence in the industry. Despite major challenges due to increasing compliance costs, reduced margins, global competition and uncertainty, the UK distribution market achieved a 6% annual growth rate between 2005 and 2010, a 5% growth between 2011 (GBP 4.1bn) and 2014 (GBP 4.5bn) and is anticipated to grow further to GBP 5.6bn by 2020 at a rate of 3.6%, which is higher than expected the GDP growth (Chemagility, 2015). According to Chemagility (2008 and 2015), the UK chemical distribution industry has experienced a high rate of growth that can be attributed to globalization and international trade, the market entry of Asian producers, the reduced product and service offerings from chemical producers and downsizing by manufacturers that led to higher utilization of distributors. However, the industry, like the rest of Europe has also experienced significant industry consolidation resulting in the overall reduction of the number of companies present and increasing even more the pressure on the survival of SMEs (Chemagility, 2008 and 2012; Key Note, 2011; Plimsoll, 2013). It is worth noting that in 2014 large enterprises and multinationals held 67% of the total UK chemical distribution market value, leaving a smaller share of 23% (GBP 1.47bn) to all other small businesses (Chemagility, 2015).

Overall, there is general agreement in the current business literature that SMEs have a strong presence in the UK chemical distribution industry, so that their performance greatly affects the industry (Plimsoll, 2013; Chemagility, 2008; Key Note, 2011; British Association of Chemical Specialties (BACS), 2014; Chemical Business Association, 2015; European Association of Chemical Distributors (FECC), 2013). Thus, it is crucial to analyze the challenges and aspects of success for SMEs operating in this industry.

4 Methodology

To date – apart from some attempts being made by industry consultants such as Districonsult and the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) -, there has been only one academic study on critical success factors for SMEs in the UK chemical distribution industry by Lampadarios (2015) and one of similar nature on a European level by Hornke (2012). Hornke’s (2012) study, conducted in 2011 and based upon 62 participating companies operating in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, identifies five critical success factors: (i) employees and employer qualifications; (ii) enlargement, diversification and specialization of portfolio; (iii) enhancement of services; (iv) focusing on specific regions and (v) expansion to international sales. Lampadarios’ (2015) research a more contemporary and country specific study establishes a positive relationship between eight factors and SMEs success in the UK chemical distribution industry. Regulatory compliance, entrepreneurial orientation, customer relations management, market and product development, prior work experience and management skills, human capital, economic environment and strategic planning are, in order of importance, the critical success factors for the industry. Findings strongly suggest that success is a multidimensional phenomenon, where both firm-internal and firmexternal factors need to be optimal simultaneously. Considerable variations between SMEs in this industry based on their size are also found, suggesting that these do not form a homogeneous group and as such different strategies are needed for different sized businesses.

This paper is part of the study conducted by Lampadarios (2015). The primary aim of that study was to identify and investigate the factors critical to SMEs success and sustainable growth in the UK chemical distribution industry. However, in order to develop a more comprehensive view of the industry and cover all aspects of success, it further attempted to identify the most important challenges that small and medium-sized chemical distributors are facing. Those are reported and discussed within this paper. It is assumed that SMEs that are able to recognize, face and overcome the challenges of their business environment, have more chances of being successful and thriving. Inevitably, the challenges are related to and somehow reflected by the success factors but have the potential to offer a deeper, more qualitative insight.

To achieve the aim of the study, a survey strategy was utilized and self-administered questionnaires – incorporating open questions – were used to collect the views of owners/managers of chemical distribution SMEs. As the collection of qualitative data was based on pre-determined themes (challenges), the use of more sophisticated methods of analysis (for instance quantitative content, thematic) was not deemed necessary and thus this research drew upon the basic principles of qualitative content analysis. This is a well-established, flexible and straightforward qualitative data analysis method (Elo et al., 2014; Finfgeld-Connett, 2014; Krippendorff, 2013; Polit and Beck, 2012; Vaismoradi et al., 2013) that represents a systematic and objective means of describing and quantifying phenomena (Bloor and Wood, 2006; Gbrich, 2007; Pope et al., 2006; Powers and Knapp, 2006; Schreier, 2012). The data was collected, collated under the predetermined categories, reduced, summarized and finally reported.

All participating companies were SMEs as defined by the European Union, i.e. enterprises employing fewer than 250 people and exhibiting an annual turnover not exceeding EUR 50mn (European Union, 2003); located in the UK; not part of another organization or belonging to a larger corporation and without any manufacturing activity and capability.

Due to the fact that there was no official statistical data on the total number of SMEs operating in the UK chemical distribution industry, a combination of industry reports (by Plimsoll, Chemagility, Key Note), information provided by business associations (the British Association of Chemical Specialties, the Chemical Business Association, the European Association of Chemical Distributors, the National Association of Chemical Distributors, the North East Process Industry cluster) and internet sources (the Chemagility online database of chemical distributors and ICIS magazine) were utilized to produce a comprehensive list and thus determine the target population for this study. Each of the identified SMEs was individually checked to ensure they fulfill the criteria of the study. However, lack of official statistical data on the target population means that allowances should be made for omissions due to human error and for the fact that the total number of SMEs operating in this industry may have changed since the time of the study.

The total number of SMEs in the UK chemical distribution industry satisfying the criteria is 180. No sampling technique has been used but instead a census was conducted. Owners and senior managers (CEOs, Managing Directors-MDs and Directors) are the key informants, an approach extensively used by other researchers as well (for instance Keskin, 2006; Lee and Cheung, 2004; O’Cass and Weerawardena, 2009; Ojala, 2009; Revell, 2007; Wilson et al., 2012). A total of 118 SMEs responded positively by returning the questionnaire, in a usable and valid form for statistical analysis, generating an overall response rate of 65.5%. Thus, it can be argued that the findings of this study offer a reliable account of the challenges faced by SMEs operating in the UK chemical distribution industry.

5 Findings

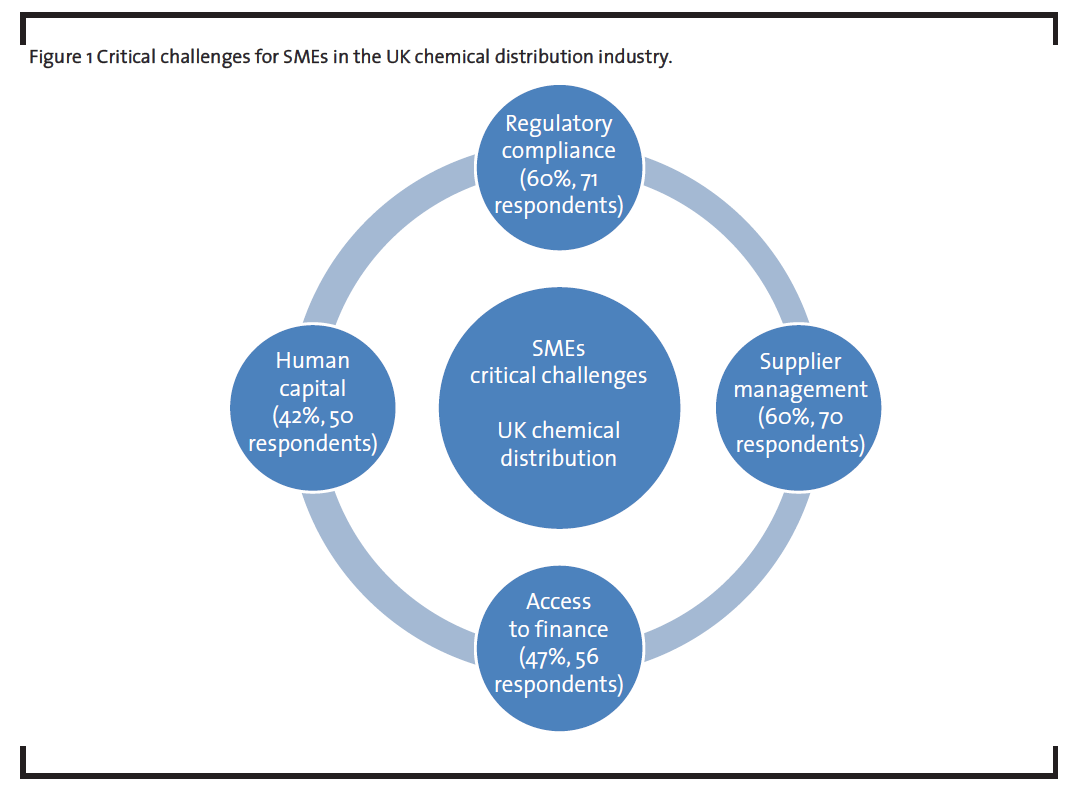

In an attempt to get a better insight into the UK chemical distribution industry, owners/managers were asked to express their views on the main challenges SMEs faced in the industry. The qualitative data collected contributes to a better and fuller understanding of the industry and provides a richer, deeper view on the mechanisms of the selected industry. The most important challenges identified are regulatory compliance, supplier management, human capital and access to finance. These are ranked by frequency of occurrence (% of population, number of respondents) and presented in figure 1.

5.1 Regulatory compliance

Regulatory compliance is highlighted not only as a critical success factor but also as a significant challenge for all SMEs in the UK chemical distribution industry: ‘REACH is the single biggest challenge for small businesses these days’ (R70); ‘…it will be interesting to see how many small companies would achieve and survive compliance…’ (R110); ‘…the biggest challenge would be to cope with the cost of regulatory requirements…’ (R45); ‘…regulation keeps increasing in complexity…’ (R20); ‘…small companies will struggle with the level of expertise required…’ (R69). The majority of owners/managers (80%, 95 respondents out of a total population of 118) identify compliance as the most important challenge.

Owners/managers consider regulatory compliance a significant drain on human and financial resources and highlight cost and resources implications with 60% of them agreeing on the matter. Complying with regulatory requirements, coping with increasing bureaucracy and offering approved, registered products in the European market alongside all other existing operations is considered a tedious task for many small businesses: ‘…you have to deal with too many things at a time…’ (R71); ‘(regulation) …needs continuous monitoring that takes time off selling our products…’ (R78); ‘…keeping up to date with regulations is time consuming and complex task…’ (R111); ‘…you need more experienced people to deal with the regulation part…’ (R65); ‘…the costs of compliance are creeping up on us…’ (R100); ‘…internal costs have increased to cope with REACH…’ (R106); ‘…you have to come up with the money to support registrations’ (R19). As a result, the need to recruit new people, invest in the business and allow for increased costs is considered a priority.

Similarly, many respondents (60 in total, 51%) comment that the increasing cost of compliance, as an increase of direct costs and advisory services, restricts the market and a number of distributors have to withdraw: ‘…many small companies will have to leave the market; they won’t be able to afford this…’ (R7); ‘…many SME owners would be thinking about selling and exiting market now’ (R73). The same applies for manufacturers as they need to make a decision of whether to stay in a market or not but also for companies (e.g. from India or China) considering entering the European market: ‘EU won’t longer be a lucrative market anymore with such high registration costs…’ (R97); ‘…the high upfront registration costs will put many manufacturers off…’ (R40); ‘…entering the market will require higher costs an expertise’ (R32).

Owners/managers (35 in total, 30%) also view regulatory compliance as a further barrier to starting up a small business in the UK chemical distribution industry: ‘…it is another challenge to consider if you are thinking of setting up something new…’ (R85); ‘…starting up will require more initial financial capital and expertise then before…’ (R60); ’…it will affect spin offs…in the past it was easier for people to start their own business…’ (R23); ‘…it makes entry more difficult’ (R26). They also express complaints about the increased bureaucracy that might eventually limit the flexibility of small businesses: ‘…bureaucracy is killing the flexibility of smaller businesses’ (R1). Respondents conclude that the current regulatory requirements definitely make the start-up of a new business more challenging with 30 of them arguing the matter.

30% of the owners/managers also identify a positive side to regulatory compliance. In the words of R95: ‘…if you can’t do business in Europe, you might as well try your luck in other markets’. Small distributors have the opportunity to explore other markets outside Europe that do not have such strict regulations and may be easier to do business with: ‘…i…’ (R68); ‘…promote your products (if possible) outside EU’ (R24). However, further financial and human resources challenges arise: ‘…it is easier said than done…’ (R14); ‘…you still need to manage the internationalization process properly’ (R74).

5.2 Supplier management

Regarding supplier management – which is highlighted by 70 respondents as a major challenge – owners/managers identified two main elements: maintaining existing suppliers and finding new ones. Based on the fact that ‘…without suppliers, you have no products and thus no business…’ (R117), it becomes obvious that small distributors should ‘…put a lot of effort into managing their sources’ (R41).

According to the respondents, SMEs should strive to become a reliable partner to their suppliers while building up their credibility, ‘…so your suppliers can trust you and see you as a business partner’ (R2). Taking into consideration a shrinking manufacturing base in the UK and with a large proportion of global manufacturing moving to India, China and the Far East, owners/managers consider suppliers ever so important: ‘…the challenge is to keep your suppliers content…’ (R56); ‘…if you keep selling, they will keep supplying…’ (R84); ‘…you need to maintain your good reputation or build one…’ (R37); ‘…be seen as a preferred distributor…’ (R70); ‘…protect your sources…others may tempt them to leave you…’ (R100); ‘…get plenty of contacts in your suppliers’ companies…’ (R16); ‘…build good, strong relationships’ (R45). Respondents further recognize that in Europe, due to regulatory requirements, there may be a restriction in existing and new suppliers so ‘…there could only be a handful of suppliers with registered products…you need to be in with one of them at least’ (R89).

A further aspect for SMEs in the UK chemical distribution industry is the need to keep adding new suppliers. 35 owners/managers express the opinion that new suppliers are very important in growing a business and are viewed as the sole source of innovation for distributors with no R&D and manufacturing capabilities: ‘…your suppliers will give you new ideas and come up with exciting products’ (R32); ‘…we can’t develop new products or predict market trends’ (R86). Small distributors have to keep updating their product portfolio and adjust their offering to customer requirements and market trends. Unlike larger companies with more resources, smaller companies have to rely more on their suppliers to do that: ‘…suppliers can help you find new markets…’ (R61); ‘…identify new applications…’ (R29); ‘…provide with all data needed to sell the product…’ (R75); ‘…provide the technical support you need…’ (R97); ‘…do joint visits to support your business’ (R111).

5.3 Human capital

50 owners/managers (42%) also identify human capital as a challenge for small businesses in the UK chemical distribution industry. Several respondents comment that finding, attracting and retaining qualified and skilled people into their business has been getting increasingly difficult: ‘…there is a lot of competition for good people’ (R42). In fact, there is general agreement that, to start with, there is a distinct lack of skilled and qualified people in the industry: ‘…we need more scientists, chemists, engineers…’ (R10); ‘…there aren’t enough technical people educated to a degree’ (R109); ‘…universities are not producing enough scientists…’ (R99); ‘…we need more people with technical understanding and background…’ (R57); ‘…need people with regulatory knowledge…’ (R36); ‘…can’t keep paying external consultants, they are too expensive…’ (R103).

In addition, 35 respondents recognize the fact that it has been getting harder for smaller businesses to attract new employees. In their opinion, this is due to two main reasons. Firstly, larger distribution companies offer better packages and career prospects: ‘…we keep losing good people to the larger companies…’ (R38); ‘…we can’t afford to offer the same salaries and benefits…’ (R44); ‘…larger distributors are very aggressive in their recruitment…’ (R23); ‘…working for a global distributor is a high prestige job…’ (R66); ‘…larger companies can offer many career paths…’ (R4); ‘…you are part of a large machine’ (R105). Secondly, smaller companies are considered more high risk, a less stable working environment and more dependent on the market conditions: ‘…young graduates think that we will go bankrupt…’ (R115); ‘…difficult to see themselves working a long time for a small business…’ (R49); ‘…we are seen as high risk employer’ (R19). Similarly, retaining employees is also highlighted as a challenge as: ‘…large companies offer lucrative packages and prospects…’ (R71) and ‘…try to poach our best people all the time’ (R64). The need to ‘…keep your employees happy and content…’ (R93) and ‘…give them no reason to leave your company’ (R26) was recognized.

Another aspect of human capital that 22% of the owners/managers highlight is that of succession planning and the replacement of senior management (Managing directors (MDs), directors, and owners). There is an agreement that succession planning is extremely important to small businesses as it could potentially affect their operation: ‘…there is a need for a smooth transition when the MD leaves…’ (R53); ‘…we will need to show that it is business as usual when I go…’ (R81). Succession planning is seen to ‘…guarantee longevity…’ (R113), ‘…ensure business continuity and stability…’ (R59), ‘…demonstrate strategic thinking’ (R14), ‘…build trust with employees but also suppliers and customers…’ (R13), ‘…is a good sign of business planning…’ (R54) and ‘…a way to sustainable growth…’ (R94). The fact that many small businesses did not have any business succession planning in place is stated by some respondents (10 owners/managers) and is seen as a challenge for the near future: ‘…it has to be done as soon as possible’ (R88).

5.4 Access to finance

Many concerns are also voiced about access to finance especially as SMEs need funding to stay in business, ‘…need to keep floating and not running out of cash…’ (R51) and‘…fuel future growth’ (R58). 56 owners/managers (47%) consider securing finance a significant challenge, especially during recession times, as financial institutions and private investors consider small businesses as high risk and do not release funds. In fact, many respondents (26 in total) feel that being refused finance has nothing to do with their company performance but due to the fact that, during recession, ‘…banks will simply not lend you money’ (R74). The need to ‘…have a business plan to show what you will do with the money…’ (R79), ‘…maintain your profitability…’ (R106) and ‘…run a tight ship on payments and payment terms…’ (R46) is also highlighted in an attempt to secure finance. Maintaining a good relationship with your lenders and building a good reputation and credit history as a business is also considered critical in attracting and securing finance from investors or banks: ‘…work closely with your bank…’ (R33); ‘…keep your investors interested in your business…’ (R107); ‘…pay on time, build and maintain a good credit score’ (R78).

6 Discussion and concluding remarks

This study identified regulatory compliance, supplier management, human capital and access to finance as the most critical challenges and therefore, prerequisites to the success of small businesses in the UK chemical distribution industry. Overall and in line with Lampadarios’ (2015) study, it is established that only when small and mediumsized distributors address and overcome all these challenges in their business environment, can they be successful and thrive. This strongly suggests that success in the UK chemical distribution industry is a multidimensional phenomenon where a number of contributing factors need to be taken into consideration and addressed simultaneously as satisfying one or two conditions does not necessarily guarantee success. The findings of this research strongly suggest the presence of interrelationships between the identified challenges. In specific, as regulatory compliance commands high levels of expertise, deep knowledge of the current legislation and an understanding of future trends (Eacott, 2014; Flavell-While, 2012; Whyte, 2012), human resources become an important element. People with experience and prior knowledge in the industry are fundamental in coping effectively with the regulatory requirements and financial impact of REACH compliance. The fact that small chemical distributors have to undertake the task of registrations, authorizations, implementing restrictions and communicating the results of chemical safety assessments (Flavell-While, 2012; Whyte, 2012), stresses even further the need for good management skills and careful handling. Meanwhile, access to finance also becomes a significant part of compliance as financial resources are required to cover all direct (e.g. registration costs, additional testing) and indirect costs (e.g. business consultants and agencies fees, recruitment, training and skills development). Lack of human and financial resources – which is an inherent characteristic of SMEs (Adams et al., 2012; Forsman, 2008; Simpson et al., 2012) – inevitably makes small chemical distributors turn to their suppliers/principals for information and advice. Supplier management – in terms of securing suppliers with technical, regulatory capabilities and resources – is integral to compliance and can create a competitive advantage against other distributors. Similarly, access to finance (e.g. for investments in new facilities) and human resources (e.g. for knowledge sharing) are prerequisites for a successful supplier management strategy. Lastly, any new investments in personnel and/or any training and skills development for existing employees requires financial resources and is dependent on careful planning.

6.1 Regulatory compliance

Despite the fact that SMEs, unlike their larger counterparts, are considered to be more flexible, adaptable and thus less being able to cope with the business environment more effectively (Adams et al., 2011; Forsman, 2008; Raju et al., 2011), this study concludes that regulatory compliance is unavoidable. Inevitably, all SMEs operating in the UK and European chemical distribution industry have to fully implement the measures necessary to comply with regulations otherwise face the real risk of being excluded from the market (ECHA, 2014; FECC, 2013). A compliance strategy needs to be developed and implemented while a long-term, flexible outlook on regulatory requirements, especially on REACH and competition law, has to be maintained. Keeping a low profile or adopting a ‘just say yes’ approach (as described in Wilson (2012)) would be meaningless. Regulations, particularly REACH, greatly impact all other challenging factors (Chemagility, 2012; FECC, 2014). Owners/managers have to carefully manage their already limited resources and weigh potential benefits against investment. Strict financial control is essential to manage the incurring costs (direct or indirect) to the business. An investment in human resources, so as to achieve the level of expertise and regulatory competence required, is necessary. Utilizing external consultants is deemed more appropriate in the initial stages of the registration process where more expertise is required. But in the long term, permanent employees are needed to manage the process. Similarly, SMEs need to develop and adjust their product portfolio based on regulatory requirements while strengthening relationships with existing and new suppliers. Throughout the compliance process and as part of their strategy, owners/managers are strongly advised to utilize any sources of support available to them, for instance the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), the European Commission and the Chamber of Commerce among others. In fact, this study raises serious concerns of whether SMEs are able to cope with the regulatory requirements without the support of the government and industry organizations due to the lack of resources (Adams et al., 2011; Forsman, 2008). Thus, the government and relevant associations carry the responsibility to reach out to SMEs to offer more support and access to resources and training in order to support their business activities.

6.2 Supplier management

The fact that chemical distribution companies do not have manufacturing capabilities also makes success dependent upon providing excellent service throughout the supply chain and not just to customers. Chemical manufacturers and suppliers need to be seen as an integral part of a small business – and its success – and as such, supplier management has to be incorporated in the customer relations management (CRM) process. This research reaches the conclusion that manufacturers and suppliers are extremely important for distribution companies as they are their only source of raw materials and innovation and the ones with capabilities to develop and modify products. To that end, SMEs in chemical distribution need to develop and nurture strong, long-term relationships with their customers and suppliers alike while continuously striving to identify and satisfy their needs. Furthermore, staying close to customer and supplier base – through increased communications, participation in exhibitions, trade shows and industry related events – enables SMEs to keep in touch with the market and identify future trends. Any opportunities to become more integrated through alliances, joint ventures and any other form of cooperation should also be explored. The importance of supplier management is further highlighted regarding market and product development (MPD). The findings of this study suggest that small chemical distributors need to obtain a good buying position and seek reliable sources and suppliers in order to implement a successful MPD strategy. SMEs can achieve sustainable growth through their existing suppliers by expanding into new product groups, new territories and extending distribution agreements. Similarly, they have the opportunity and should capitalize on suppliers’ resources and capabilities such as testing, sampling, R&D and new product development (NPD) and in turn provide feedback on market trends and changes in customer preferences. The main conclusion is that there is an imperative need for owners/ managers to engage more in supplier management, with the most important elements being knowledge development and sharing, development of business processes and investment in physical facilities or software in line with key suppliers’ systems and processes.

6.3 Human capital

Human capital is found to be one of the most important resources for SMEs operating in the UK chemical distribution industry. This study ascertains that this is a very customer-focused and customer- facing industry with the human factor having a significant influence on business and further argues that the services offered by chemical distributors depend more on human rather than on technical or logistical resources. This research further concludes that small businesses in the UK chemical distribution industry with a higher degree of human capital have more chances of being successful and achieving sustainable growth. Having identified a shortage of highly skilled, technically qualified employees in the industry, the findings strongly suggest that recruiting individuals with industry-specific experience, skills and qualifications has a big impact on the performance of the business. A further conclusion is the fact that SMEs in this industry, depending on their size, have a different approach for developing human capital. Smaller companies have an informal approach utilizing existing employees while larger ones prefer a formal approach. The study recognizes that a fine balance between using a combination of recruiting new individuals with high skills from the external labor market and internally developing the skills of current employees needs to be kept and further establishes the need for SMEs owners and managers to attain and develop human resource management skills. This research reveals that owners/managers often lack many skills in managing certain aspects of their businesses and acknowledges the need for further training and skills development. Lastly, the importance of succession planning is firmly established. For reasons of stability and business continuity, formal or informal arrangements need to be made in good times and need to be communicated accordingly. This would reduce uncertainty during times of change and ensure smooth transitions.

6.4 Access to finance

Owners/managers identify access to finance (funding) as the single, most important aspect of the economic environment; a factor that could potentially be very restricting to growth. All small businesses in this industry, independent of their size and market conditions, need funding at some point in their life (whether it is to start up, grow or cope with cash flow shortages). This finding is consistent with the work of many authors who recognize the importance of the availability of financial resources in a market and argue that a lack of available cash flow or external finance hinders SMEs success and growth opportunities (Amoros et al., 2013; Calcagnini and Favaretto, 2012; Guo and Shi, 2012; Carter and Van Auken, 2005; Korunka et al., 2010; Medina et al., 2005). The importance of access to funding becomes paramount when, especially during recession periods, financial institutions are reluctant to lend money to SMEs – because of their high risk and low collateral – and private investors similarly restrict access to funds further affecting small business growth. This research concludes that it is imperative for owners/managers and entrepreneurs to secure multiple sources of finance and fully utilize all available options in the market(s) they operate in. In detail, chemical distribution SMEs are urged to look for more perfect capital markets where more financing channels and better access to capital and credit schemes are available, especially when exporting. Similarly, it is important that owners/managers and prospective entrepreneurs seek markets where government policies (e.g. the availability of grants, loan guarantees, subsidized interest rates) and support are available for small businesses. Of course, once funding is secured, there is a still need to monitor cash flow and liquidity proactively, focus on planning and maintain a close and trustful relationship with investors and lenders. However, even if a business has sufficient funding, it still needs to be able to deal with and manage unforeseen cash flow shortages. The findings reveal that the chemical and chemical distribution industry is largely handled on credit terms and a discrepancy between the supplier and customer payment terms is not out of the ordinary. Managing payment terms and balancing cash flow under these conditions creates a further need for finance services and flexible borrowing options. Similarly, during times of recession, an increase in bad debts is not uncommon and small business need to be prepared. This research recognizes that losses due to bad debts create cash flow shortages, put a considerable strain on SMEs and, in extreme cases, push them into bankruptcy. The latter scenario mostly applies to micro businesses depending heavily on very few customers. At this point, this study makes a further distinction between smaller and larger chemical distribution SMEs, with the first being more vulnerable and the latter being able to cope with bad debts more efficiently due to their size and funding options. Therefore, cash flow and credit terms management alongside building up a contingency fund for difficult times become crucial.

6.5 Implications for practice

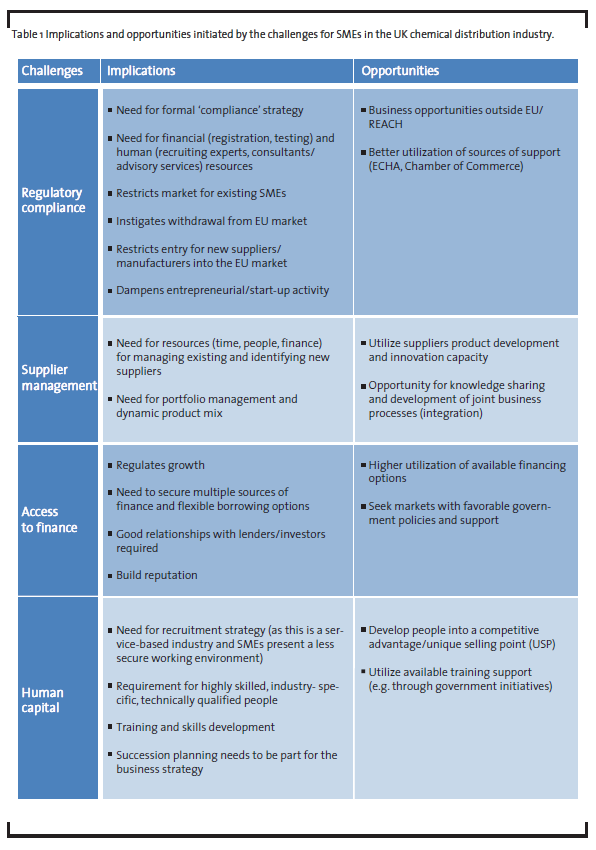

This paper addresses a gap in the UK chemical distribution industry as it provides an account of the challenges small and medium-sized distributors are facing and uncovers a number of contributing factors to their success. Based on the findings, table 1 provides a summary of implications and opportunities for SMEs in the UK chemical distribution industry. SMEs owners/managers can utilize the findings of this study to strategize, run their businesses more efficiently and effectively by concentrating their efforts and resources to the areas that really make a difference in their business, plan and prepare for the future including challenges in their planning process and addressing any issues in the very early stage, improve their decision-making process and uncover and address training needs such as strategic and financial planning skills or recruitment. The government, policy makers and financial institutions may utilize the findings of this study to develop and implement policies directed at SMEs in the specific industry, improve and develop the necessary support infrastructure, extend the nature and the range of advice and offer training and education for SME owners, managers and employees. Non-government, industry-specific organizations such as the FECC, the Chemical Business Association (CBA) and the British Association of Chemical Specialties (BACS), also benefit from this research as it increases their understanding of the industry, especially from a small business perspective. It also provides the knowledge for these associations to approach and recruit new members, especially SMEs that have always been difficult to approach or the ones that did not see a value in joining before. Moreover, chemical manufacturers and suppliers are able to get a deeper, more complete understanding of the market and the SMEs operating within. Therefore, they would be in a position to evaluate, formulate and implement their distribution channel strategy in a more efficient and effective way.

References

Adams, J. H., Khoja, F. M., Kauffman, R. (2012): An Empirical Study of Buyer–Supplier Relationships within Small Business Organizations, Journal of Small Business Management, 50 (1), pp. 20-40.

Amorós, J. E., Bosma, N. S., Levie, J. (2013): Ten Years of Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: Accomplishments and Prospects, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 5 (2), pp. 120-152.

Arasti, R., Zandi, F., Talebi, R. (2012): Exploring the Effect of Individual Factors on Business Failure in Iranian New Established Small Businesses, International Business Research, 5 (4), pp. 2-11.

Beaver, G. (2002): Small Business, Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Development, Pearson Education, Harlow.

Bee, T.K., Chelliah, J. (2013): Why are Private Equity Firms Acquiring Chemical Distributors Worldwide?, The Journal of International Management Studies, 8 (1), pp. 108-113.

Benzing, C., Chu, H. M., Kara, O. (2009): Entrepreneurs in Turkey: A Factor Analysis of Motivations, Success Factors, and Problems, Journal of Small Business Management, 47 (1), pp. 58–91.

Blackburn, R., Kovalainen, A. (2009): Researching small firms and entrepreneurship: Past present and future, International Journal of Management Reviews, 11 (1), pp. 127-148.

Bloor, M., Wood, F. (2006): Keywords in Qualitative Methods: A Vocabulary of Research Concepts, 1st ed., SAGE Publications, London.

Bonet, F.P., Armengot, C.R., Martín M.A.G. (2011): Entrepreneurial success and human resources, International Journal of Manpower, 32 (1), pp. 68-80.

Boston Consulting Group (2010): Opportunities in Chemical Distribution: Optimizing Marketing and Sales Channels, Managing Complexity, and Redefining the Role of Distributors, available at https://www.bcg.com/documents/file37956.pdf, accessed 21 December 2015.

Boston Consulting Group (2013): The Growing Opportunity for Chemical Distributors: Reducing complexicity for producers through tailored service offerings, available at https://www.bcgperspectives. com/content/articles/process_indu stries_supply_chain_management_growing_op portunity_chemical_distributors/#chapter1, accessed 20 February 2014.

Brenntag (2010): About us, available at http://www.brenntag.com/, accessed 16 September 2015.

British Association of Chemical Specialties (BACS) (2014): About us, available at http://www.bacsnet. org/, accessed 7 April 2015.

Burns, N. A. (2010): Chemical Distributors, available at http://www.neilaburns.com/chemical-distributors/, accessed 21 December 2015. C

alcagnini, G., Favaretto, I. (2012): Small Businesses in the Aftermath of the Crisis: International Analyses and Policies, Springer-Verlag Berlin, Heidelberg, New York.

Carter, R. and Van Auken, H. (2005): Bootstrap financing and owners’ perceptions of their business constraints and opportunities, Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 17 (2), pp. 129-144.

CEFIC (2012): Facts and figures: the European chemical industry in a worldwide perspective, European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC), available at http://www.cefic.org/Facts-and-Figures/ Facts–Figures-Brochures, accessed 14 February 2014.

CEFIC (2013): The European chemical Industry: Facts and Figures 2013, available at http://www.cefic. org/Facts-and-Figures, accessed 15 May 2015.

Chawla, S. K., Khanna, D., Chen J. (2010): Are Small Business Critical Success Factors Same in Different Countries?, SIES Journal of Management, 7 (1), pp. 1-12.

Chemagility (2008): UK Chemical Distributor Market Report 2008: Information, Insight and analysis of the UK Chemical distribution industry, Chemagility, Surrey.

Chemagility (2012): A Global Perspective on the World Chemical Distribution Market, First Panel Session: Chemical Distribution Industry Landscape, presented at the FECC Annual Congress, Lisbon, May 21-23, 2012, available at http://www. assicconline.it/menu/documents/06_brown.pdf, accessed 29 May 2015.

Chemagility (2015): United Kingdom Chemical Distribution Report 2015, Chemagility, Surrey.

Chemical Business Association (2015): CBA Supply Chain Trends March 2015, available at http:// www.chemical.org.uk/news/cbanews/cbasupplychaintrendsmarch2015. aspx, accessed 17 April 2015.

Department for Business and Innovation (2014): Statistical release: Business population estimates for the UK and regions 2014, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/ uploads/attachment_data/file/377934/bpe _2014_statistical_release.pdf, accessed 27 April 2015.

Districonsult (2009): Chemical Distribution in 2009: Challenges and Uncertainties, available at http://www.districonsult.com/, accessed 15 June 2015.

Districonsult (2010): Wheels of change spin in distribution, available at http://www.districonsult .com/en/index-districonsult%2Bnewsletter-1-31%2B~%2Bwheels%2Bchange%2Bspin%2Bdistribution. html, accessed 24 February 2014.

Districonsult (2011): Oligopsony or Monopsony?, available at: http://www.districonsult.com/en/ index-di s t r i consul t%2Bnews let ter-1-33%2B~%2Bsmiling%2Bfaces%2Bdespite%2Bcha llenges%2Bahead.html, accessed 11 May 2013.

Districonsult (2012): Chemical Distribution in 2012: What’s next on the horizon?, 6th Brazilian Congress of Chemicals and Petrochemical Distributors (EBDQUIM), Praia do Forte (Bahia), 16th March 2012, available at http://www.associquim. org.br/ebdquim2012/palestras/Ebdquim2 012_G%C3%BCentherEberhard.pdf, accessed 10 May 2013.

Districonsult (2013): Old Game – New Rules? Chemical Distribution in the Age of Volatility, available at http://www.districonsult.com/en/indexdistriconsult% 2Bnewsletter-1-34%2B~%2Bold%2 Bgame%2Bnew%2Brules%2B2013.html, accessed 27 February 2015.

Dobbs M., Hamilton R. T. (2007): Small business growth: recent evidence and new directions”, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 13 (5), pp. 296-322. European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) (2014): About us, available at http://echa.europa.eu/, accessed 19 January 2015.

Elo, S., Kaariainen, M., Kanste, O., Polkki, T., Utriainen, K., Kyngas, H. (2014): Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness, SAGE Open, January-March 2014, pp. 1-10.

European Union (2003): Commission Recommendation of 6 May 2003 Concerning the Definition of Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, Official Journal of the European Union, 124 (1), pp. 36-41.

European Union (2015): Fact and figures about the EU´s Small and Medium Enterprise (SME), available at http://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/access -to-markets/index_en.htm, accessed 21 December 2015.

FECC (2011): Communication in the supply chain – distributors ‘challenges, ECHA – ENES Meeting 24-25 November 2011, Brussels, available at https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/13587/ echa_enes_jensen_korte_en.pdf, accessed 14 May 2015.

FECC (2013): The Chemical distribution Sector in Europe, available at http://www.fecc.org/aboutfecc/ the-chemical-distribution-sector-in-europe, accessed 21 December 2015.

FECC (2015): European business plan 2015, available at http://www.fecc.org/images/stories/downloads/ GTDP/2014/FECC_BusPlan_2015_def.pdf, accessed 21 December 2015.

Floren, H. (2006): Managerial work in small firms: summarising what we know and sketching a research agenda, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 12 (5), pp. 272-288.

Forsman, H. (2008): Business development success in SMEs: a case study approach, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15 (3), pp. 606-622.

Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2014): Use of content analysis to conduct knowledge-building and theorygenerating qualitative systematic reviews, Qualitative Research, 14 (3), pp. 341-352.

Franco, F., Haase, H. (2009): Failure factors in small and medium-sized enterprises, qualitative study from an attributional perspective, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6 (4) pp. 2-11.

Franco, M., Haase, H. (2010): Failure factors in small and medium-sized enterprises: qualitative study from an attributional perspective, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6 (4), pp. 503-521.

Gbrich, C. (2007): Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction, 1st ed., Sage Publications, London.

Gibb, A. (2000): SME policy, academic research and the growth of ignorance, mythical concepts, myths, assumptions, rituals and confusions, International Small Business Journal, 18 (3), pp. 13-36.

Gray, D., Saunders, M., Goregaokar, H. (2012): Success in challenging times: Key lessons for UK SMEs, University of Surrey, Surrey.

Guo, T., Shi, Z. (2012): Systematic Analysis on the Environment of Innovative Small and Medium Enterprises, 2012 International Conference on Applied Physics and Industrial Engineering, Physics Procedia, 24 (2), pp.1214-1220.

Halabi, C. E., Lussier, R. N. (2014): A model for predicting small firm performance, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 21 (1), pp. 4-25.

Health and Safety Executive (HSE) (2015): REACH: Definitions, available at http://www.hse.gov.uk/ reach/definitions.htm#distributor, accessed 20 April 2015.

Hitt, M.A., Ireland, R.D., Camp, M., Sexton, D.L. (2001): Strategic entrepreneurship: entrepreneurial strategies for wealth creation, Strategic Management Journal, 22 (1), pp. 479-491.

Holmes, P., Hunt, A., Stone, I. (2010): An analysis of new firm survival using a hazard function, Applied Economics, 42 (1), pp. 185-195.

Hornke, M. (2012): Chemical Distribution 2012, available at http://www.chemanager-online.com/ file/track/11755/1, accessed 20 February 2015.

Hornke, M. (2013): The future of chemical distribution in Europe: Customer relations as key value lever, Journal of Business Chemistry, 9 (2), pp. 65-66.

Jung, U., Wolleswinkel, R., Hoffmann, C., Rothman, A. (2014): Specialty Chemical Distribution-Market Update, available at https://www.bcgperspectives. com/content/articles/process_industries_ go_to_market_strategy_specialty_chemical_ distribution_market_update/?chapter=2, accessed 17 April 2015.

Kader, R. A., Mohamad, M. R., Ibrahim, A. A. (2009): Success factors for small rural entrepreneurs under the one-district-one-industry programme in Malaysia, Contemporary Management Research, 5 (2), pp. 147-162.

Keskin, H. (2006): Market orientation, learning orientation, and innovation capabilities in SMEs, European Journal of Innovation Management, 9 (4), pp. 396-417.

Key Note, (2011): Business ratio Report: Chemical Distributors UK, Key Note Ltd., Richmond upon Thames.

Key Note (2013): Business ratio Report: Chemical Distributors UK, Key Note Ltd., Richmond upon Thames.

Krasniqi, B. A., Shiroka-Pula, J., Kutllovci, E. (2008): The determinants of entrepreneurship and small business growth in Kosova: evidence from new and established firms, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 8 (3), pp. 320-342.

Korunka, C., Kessler, A. Hernnann Frank, H., Lueger, M. (2010): Personal characteristics, resources, and environment as predictors of business survival, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83 (2), pp. 1025-1051.

Krippendorff, K. (2013): Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology, 3rd ed., SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Kumar, K., Boesso, G., Favotto, F., Menini, A. (2012): Strategic orientation, innovation patterns and performances of SMEs and large companies, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19 (1), pp. 132-145.

Lampadarios, E. (2015): Critical success factors for SMEs: an empirical study in the UK chemical distribution industry, PhD Thesis, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds.

Lampadarios, E., Kyriakidou, N., Smith, G. J. (n.d.): Towards a new framework for SMEs success: a literature review, International Journal of Business and Globalisation, in press.

Lee, M. K. O., Cheung, C. M. K. (2004): Internet Retailing Adoption by Small-to-Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs): A Multiple-Case Study, Information Systems Frontiers, 6 (4), pp. 385-397.

Lin, W.B. (2006): A comparative study on the trends of entrepreneurial behaviours of enterprises in different strategies: Application of the social cognition theory, Expert Systems with Applications, 31 (1), pp. 207-220.

Lussier, R.N. (1995): A Nonfinancial Business Success Versus Failure Prediction Model for Young Firms, Journal of Small Business Management, 33 (1), pp. 8-20.

Lussier, R.N., Halabi C.E. (2010): Three-Country Comparison of the Business Success versus Failure Prediction Model, Journal of Small Business Management, 48 (3), pp. 360-377.

McLarty, R., Pichanic, M., Sarapova, J. (2012): Factors Influencing the Performance of Small to Medium- Sized Enterprises: An Empirical Study in the Czech Republic, International Journal of Management, 29 (3), pp. 36-47.

Medina, C. C., Laved A. C., Cabrera, R. V. (2005): Characteristics of Innovative Companies: A Case Study of Companies in Different Sectors, Creativity and Innovation Management, 3 (14), pp. 272-287.

Mortelmans, S., Reniers, G. (2012): Chemical distribution in Belgium from 2007 to 2010: An empirical study, Journal of Business Chemistry, 9 (2), pp. 105-113.

National Association of Chemical Distributors (NACD), (2005): The Chemical Distribution Industry & Its Focus on Security, available at http://www.chemserv.com/pdf/NACD%20Chem icalSecurity.pdf, accessed 15 February 2015.

Office of the Advocacy United States Small Business Association (2003):2003 State Small Business Profile: United States, available at http://www.sba.gov/advo/stats/profiles/03us.pd f, accessed 22 November 2014.

O’Cass, A., Weerawardena, J. (2009): Examining the role of international entrepreneurship, innovation and international market performance in SME internationalisation, European Journal of Marketing, 43 (11), pp. 1325-1348.

Ogundele, O. J. (2007): Introduction to Entrepreneurship Development, Corporate Government and Small Business Management, 1st ed., Molofin Nominees, Lagos.

Ojala, A. (2009): Internationalization of knowledgeintensive SMEs: The role of network relationships in the entry to a psychically distant market, International Business Review, 18(3), pp. 50-59.

Perks, K. (2006): Influences on strategic management styles among fast growth medium-sized firms in France and Germany, Strategic Change, 15 (2), pp. 153-164.

Philip, M. (2011): Factors Affecting Business Success of Small & Medium Enterprises (SMEs), Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 32 (4), pp. 635-657.

Plimsoll (2013): Plimsoll Analysis: UK Chemical Wholesalers & Distributors Industry – Individual Company Analysis, Plimsoll Publishing Limited, Stockton on Tees.

Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T. (2012): Nursing research: Principles and methods, Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

Pope, C., Ziebland, S., Mays, N. (2003): Analysing qualitative data, in: Pope, C. and Mays, N. (eds.), Qualitative Research in Health Care, 3rd ed., Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, pp. 63-81.

Powers, B., Knapp, T. (2006): Dictionary of Nursing Theory and Research, 3rd ed., Springer Publishing Company, New York.

Raju, P. S., Lonial, S. C., Crum, M. D. (2011): Market orientation in the context of SMEs: A conceptual framework, Journal of Business Research, 64 (1), pp.1320-1326.

Revell, A., Rutherfoord, R. (2003): UK environmental policy and the small firm: Broadening the focus, Business Strategy and the Environment, 12 (2), pp. 26-35.

Rogoff, E.G., Lee, M.S., Suh, D.C. (2004): “Who Done It?” Attributions by Entrepreneurs and Experts of the Factors that Cause and Impede Small Business Success, Journal of Small Business Management, 42 (4), pp. 364–376.

Ropega, J. (2011): The Reasons and Symptoms of Failure in SMEs, International Advanced Economic Research, 17 (2), pp. 476-483.

Schreier, M. (2012): Qualitative content analysis in practice, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Simpson, M., Padmore, J., Newman, N. (2012): Towards a new model of success and performance in SMEs, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 18 (3), pp. 264-285.

Smallbone, D., Welter, F., Voytovich, A., Egorov, I. (2010): Government and entrepreneurship in transition economies: the case of small firms in business services in Ukraine, Service Industries Journal, 30 (5), pp. 655-670.

Storey, D.J., Greene, F.J. (2010): Small Business and Entrepreneurship, Pearson Education, London.

UK Companies Act (2006): Contents, available at www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/46/contents, accessed 21 January 2014.

Unger, J. M., Rauch, A., Frese, M., Rosenbusch, N. (2011): Human capital and entrepreneurial success: A meta-analytical review, Journal of Business Venturing, 26 (1), pp. 341-358.

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., Bondas, T. (2013): Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study, Nursing and Health Sciences, 15 (3), pp. 398-405.

Wilson, C. D. H., Williams, I. D., Kemp, S. (2012): An evaluation of the impact and effectiveness of environmental legislation in small and medium‐sized enterprises: Experiences from the UK, Business Strategy and the Environment, 21 (3), pp. 141-156.