Brexit and the UK chemical supply chain: A commentary on potential effects

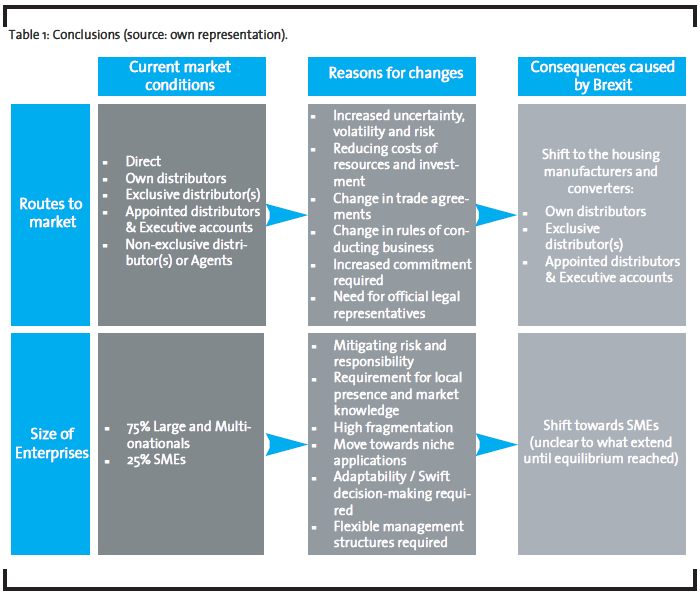

Businesses assume that in developed countries, political stability is guaranteed. However, the result of the British referendum (June 2016) has altered the political arena and introduced an era of uncertainty and volatility, referred to as ‘Brexit’. The UK chemical industry and its supply chain need to respond and changes might be in order. The routes to market could be changing and there appears to be a shift towards chemical distribution; particularly towards official and appointed chemical distributors rather than direct business and non-exclusive distributors. The emerging market conditions also demand higher flexibility and adaptability, pointing in the direction of small businesses (SMEs) rather than larger enterprises. Nevertheless, as these are the early stages of this process, it is difficult to ascertain whether the initial effects would be of a permanent or temporary nature until a state of equilibrium is again reached in the market.

1 Introduction

Without a doubt, the political environment affects and shapes business strategy and clearly impinges on business activity. No company – national or international, large or small – can conduct its business without taking into account the influence of the political environment in which it operates. The nature of this system, its institutions and processes, government involvement in the workflow of the economy and its attempts to influence market structure and behaviour – for instance laws and regulations, tax policies, financial support and loans – but most importantly government decisions have a significant impact on short and long term planning and performance. With political stability seen as a precondition for high industrialization, innovation and business success, recent events in the European political arena have altered the landscape and increased the level of volatility and uncertainty. The results of the British referendum (June 2016) have triggered an unprecedented set of events, addressed under the ‘Brexit’ umbrella, leading Europe and the UK into unchartered territory alongside with all businesses operating in this geographical region.

An industry that is most likely to be affected by the aforementioned changes is chemical distribution. As being a significant contributor to the UK economy and employment, the potential effect(s) of Brexit on the UK chemical supply chain become of particular interest and are worth discussing in further detail. Regarding the industry itself, despite the fact that it is well-established and mature, it appears to be highly fragmented and therefore still subject to strong consolidation trends as well as high mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activities. The ever-increasing environmental (climate change, reduction in emissions, sustainable development, green chemistry requirements, corporate social responsibility) and regulatory (REACH, Classification, Labelling and Packaging of substances and mixtures (CLP), Biocidal Products Regulation (BPR), EU competition and information exchanging rules) pressures further contribute to the dynamicity of the market. Globalization and advancements in technology and logistics have already had a profound effect on the supply chain. Increased direct global competition, mainly from Europe and Asia, has caused a shift in the manufacturing focus and investment, with the UK now moving towards high value, niche, technologically advanced applications and markets away from commodities. Inevitably, the manufacturing centre has gradually but steadily moved outside the UK, with only a few large manufacturers remaining alongside a number of smaller, but with strong presence, converters. Accordingly, traditional markets for instance Household, Metalworking and Lubricants, Textile, Leather and Paper, Agrochemicals, Coatings, Plastics, Food, Water treatment, Oilfield and Construction declined in recent years, whereas Pharmaceuticals, Nutraceuticals, Aerospace, Electronics and Personal Care segments presented growth and continuous development. It appears that even in traditional markets the focus is on specialized and niche applications. Consequently, research, product development and innovation remain relatively strong with several R&D centres located in the country. The North East, North West, Yorkshire, Humber and Scotland regions are still the main manufacturing areas. The medium to long-term trend appears to be a decline in the manufacture of large volume-low margin chemicals and specialization within the manufacturing sector (Chemistry Growth Strategy Group, 2014). This is going to be accompanied by an increase in the import of bulk chemicals and fuels and associated storage and distribution (Health and Safety Executive, 2014).

The underlying objective of this commentary is to discuss the potential effect(s) the Brexit has on the UK chemical supply chain in consideration of the different routes to market and the size of the enterprises (SMEs and LMNEs).

2 UK Chemicals distribution supply chain

Chemical manufacturers have traditionally distributed their own products and direct supply continues to account for around 90% of the total global distribution, leaving a 10% share for third-party distributors (Boston Consulting Group, 2010; IMAP, 2015). Direct supply is expected to continue for large end-users, accounting for the bulk of producers’ output (Angermann M&A International, 2015). However, third-party distribution remains a vital link in the supply chain process as it offers a more flexible, cost-saving and value-adding way to increase market reach, especially to smaller customers (Grand View Research, 2013). As such, in the chemical industry, there is a very clear distinction between direct (including own distribution arm and subsidiary) and third-party supply, incorporating official (exclusive and appointed) distributors, agents (these do not take ownership of the product) and trading companies (these do not provide value added services) (IMAP, 2015). Specifically for the UK chemical industry, Chemagility (2008) identifies the typical supply chain arrangement and distinguishes the market entry strategies for overseas chemical producers into: (i) indirect export, (ii) direct export and (iii) local presence. Indirect export involves the use of chemical traders and export houses. Local presence refers to local production through direct presence or local ownership. Direct export incorporates: (i) direct sales from plant to customer (ii) the presence of a local office and/or subsidiary (own distribution arm), (iii) agents and (iv) distributors (appointed, exclusive and non-appointed).

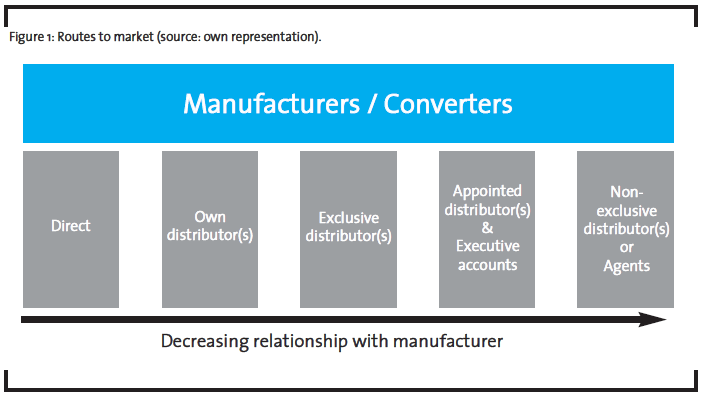

Based on above and with respect to the UK chemicals supply chain, five (5) routes to market have been identified. These are presented in Figure 1 below.

In more detail, manufacturers and converters may choose to promote their products either direct (i) – for instance Croda Chemicals with a policy not to use distributors – or through their own distribution (ii) arm to the end customer; for instance the case of BASF and BTC, where the latter is part of the same group but acts as a distributors of the former. There, all sales, marketing and logistical activities are undertaken and managed by the manufacturer and converter.

The only other way to reach customers and markets is through a third party distributor. Depending on the strength of the relationship (Chemagility, 2015 and 2008), these can be distinguished in:

(iii) Exclusive: All business is conducted through distributors-partners. There is often a formal, longterm agreement between the distributor and the chemical manufacturer – the ‘Principal’. These buy and sell chemicals from producers and take title to the goods, responsibility for stocking and warehousing, before selling the products on to their customers under their own or their principal’s brand name.

(iv) Appointed: Equally to the exclusive but with presence of executive accounts where the distributor is excluded from selling to certain companies, for instance Sasol and Shell Chemicals.

(v) Non-exclusive distributors: Operating under a traditional buy-sell arrangement, where the relationship is very loose and there is little commitment or loyalty on either side or agents. The latter do not take title to or stock goods, but receive a commission for their contribution in helping a manufacturer complete a sale. ‘Chemical trader’ is another term used to describe this type of distributors. As they are involved with the purchase and resale of commodities and buy from the producer or supplier offering them the best deal at the time. There is no close, long-term relationship with the manufacturer and they mostly rely on their suppliers’ logistics to serve their customers.

Considering the market conditions (e.g. globalization, international trade, the market entry of Asian producers) and gradual decline in the manufacturing activity (e.g. reduced product and service offerings, downsizing), the strong presence and higher utilization of chemical distributors in the UK chemicals supply chain will be expected. Manufacturers and converters need to deal with environmental and regulatory pressures, increased competition through globalization, high mergers and acquisitions activity, a need for innovation and raw materials availability as well as costs. Simultaneously, they are required to supply a wide range of products in differing quantities to a hugely diverse customer base. The varied degree of customer fragmentation, the strong presence of small customers in many markets and the differences in the composition of the customer by industry are also a particular challenge, as these require the infrastructure and processes to handle low volumes or a high diversity of products. Local presence is many times a necessity to appreciate and address the individuality of each market.

Distribution – against direct supply – comes as a business ‘phenomenon’ that reduces the complexity of product distribution respectively customer management and becomes a mean to mitigate costs and trade-related risks. Chemical distributors alleviate environmental and regulatory pressures and minimize logistical complications. They increase market reach to smaller customers (with very specific needs on technical, regulatory and logistical level) and niche, speciality industries while utilizing local knowledge and providing critical market information and feedback. Above all, they support manufacturers and converters concentrate on what they do best: manufacturing. In the recent years though, the distinction between ‘manufacturers’ and ‘distributors’ has become increasingly blurred, as an extensive range of services and products are merged to provide differentiated value-adding solutions (i.e. custom blending, bulk and non-bulk repackaging, managing customer inventories, imparting technical training and support).

With regards to the UK chemical distribution market, the industry mainly consists of large enterprises and multinationals (LMNEs) accounting for about 75% of the total market value and a very interesting mix of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) holding the remaining 25% share (Chemagility, 2015). SMEs are enterprises that employ fewer than 250 people and have an annual turnover not exceeding EUR 50 million and an annual balance sheet total not exceeding EUR 43 million (European Union, 2003).

At this point, a distinction must be made between LMNEs and SMEs, as their ‘modus operandi’ is to become a point of differentiation in the Brexit era. In fact, SMEs have several features that distinguish them from larger firms that could potentially be a strong point of differentiation and a source of competitive advantage under the current market conditions. The absence of complex formal management structures (mostly flat) and centralized decision-making (characteristic dominance of owner-managers in decision-making) combined with the lack of internal labour markets, provide SMEs with the distinct advantage of flexibility. This enables them to respond quickly and effectively to changes in the business environment and adapt to market trends. Despite the fact that smaller businesses have a limited customer base and fewer resources (financial, human, physical) available, they manage to maintain a distinct closeness to their customers, identifying needs and requirements in ‘real’ time. Consequently, they are in a better position to accommodate and service smaller customers and niche, specialized markets. Similarly, the absence of formality in the internal and external information and communication systems further improves response times and problem-solving, making SMEs more responsive than their larger counterparts. Even the fact that they tend to concentrate on current performance rather than taking a strategic focus and often engage in management ‘fire-fighting’, implies a high level of flexibility, adaptability and responsiveness to market changes.

3 The ‘Brexit’ effect

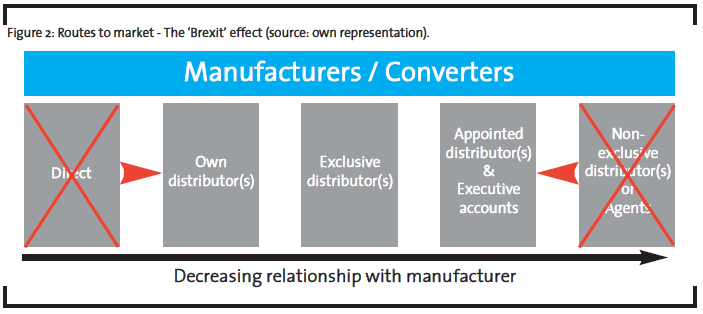

Nevertheless, following the results of the British referendum in 2016, the above described working model might easily change (please refer to figure 1). Even though Article 50 has not been activated, so officially the ‘Brexit’ era has not set up on the markets yet, reverberations of the decision for the withdrawal can be felt. Despite continuous speculations and scenarios on the potential effects, so far just a few aspects have become visible to the public and industry alike. Uncertainty appears to be the only remaining constant as the UK moves into uncharted territory. To that end, ‘Brexit’ needs to be investigated more as a phenomenon over a period of time rather than a singular event. However, it is worth noting that, as these are the early stages of the UK’s withdrawal, it is difficult to ascertain whether the initial effects, as argued in this commentary, would be of a permanent or temporary nature until a state of equilibrium has reached the market again.

Regarding the UK chemicals supply chain, speculations and scenarios have already started causing some destabilization (definitely some increased strategizing activity) that could potentially inflict change on the routes to market. In fact, it is the continuing uncertainty that has been acting as a catalyst for these changes. With the markets being uncertain about when article 50 will be activated, there are speculations about the new landscape, for instance the new trade agreements between the UK and EU/ROW, existing regulations (REACH, BPR, CLP) and rules of conducting business, for example information exchange, competition laws and local representation. From a manufacturer and converter’s point of view, it would be extremely difficult to strategize under these volatile conditions and with no clear strategy in place; the risk and potentially the cost of doing direct business in the UK could increase. During times of uncertainty and increased risk, distributors appear more appealing against direct supply as, due to local presence and market knowledge, are better equipped to deal with uncertainty and can become an effective mean to reduce and mitigate risk. They are also an effective way of keeping costs down for larger manufacturers in terms of human and physical resources and capital expenditure as well as coping with an ever-increasing level of market fragmentation. A further important influencing factor for distribution will be the distributors’ information sharing and market intelligence input, for instance market conditions, key contemporary and future trends, opportunities, competition as well as their contribution towards demand forecasting and planning, both invaluable assets to manufacturers’ operations.

Therefore, there are clear indications that ‘Brexit’ could not only affect the routes to market but potentially shift the focus towards chemical distribution (as presented in Figure 2). Conversely, in times of hardship, a strong relationship and commitment including a good reputation on both sides is required, putting the non-exclusive distributors and agents at a disadvantage. The focus therefore might be on exclusive, appointed and own distributors who under formal distribution agreements and partnerships, would be called upon to manage uncertainty, change and deal with complications, bureaucracy and risks for the foreseeable future. In addition, this would also lead to an appropriate set of policies and procedures in place, adjusted to local market needs and requirements, to ensure proper management of the suppliers’ products up to the end-users. Similarly, they could act as official legal representatives in the UK market, addressing legislative requirements so manufacturers and converters are able to focus on their core competences mainly manufacturing, logistics, research and product development as well as process improvements.

At this point, it is worth noting that even though current conditions seem to favour and ‘push’ towards exclusive, appointed and own distributors, this does not necessarily mean that direct business would not be a viable option after the withdrawal. The main argument remains that the former appear to be a more sustainable and cost-effective route to manage uncertainty, risk and high market volatility instead of the latter where strategizing and resource commitment is essential.

Considering the fact that the UK chemicals industry remains dynamic in the least, price sensitive, highly fragmented and continues to move towards more specialized, technically focused, niche applications, it is becoming apparent that SMEs might be a better supply position than LMNEs. Thus, it appears that the inherent characteristics of smaller businesses might be more suited for the current market conditions, providing them with a distinct advantage. Whether this advantage can be sustained in the long term – considering that there will be a reaction from larger and multinational companies – remains to be seen. At the same time, Brexit has significantly increased uncertainty and volatility in the market place, conditions that not only favour distribution in general but also require the flexibility, adaptability and quick responses that only smaller businesses can offer. As such, chemical distribution SMEs, due to their size, flexible management structure, informal strategy and quick decision-making should be able to respond more positively and timely to these conditions.

Overall, both Brexit and the current industry conditions seem to be favouring SMEs as a route to the UK chemicals market. Owners and managers would need to capitalize on the opportunity and adapt to the emerging landscape. An improvement on existing business practices is required with focus on performance, increasing competitiveness and ensuring business continuity. It is also becoming imperative for manufacturers and converters to make informed decisions regarding the assessment and selection of small chemical distributors to access the UK market. Likewise, various stakeholders need to focus on improving strategy formulation and decision-making process in order to support chemical distribution SMEs. Further research in the UK chemical distribution industry during the Brexit era is required to follow up on existing research (for instance Lampadarios, 2016a, b, c and d).

An equally interesting aspect of Brexit that is worth investigating and discussing in the future – as it falls slightly outside the scope of this commentary, but is most certainly related – is the effect it would potentially have on globalization. With globalization and international trade being key drivers for the chemical distribution industry in the recent years, a vote to leave the EU – thus, in a way, rejecting trade openness and labour movements – is causing serious concerns. In fact, Brexit is viewed as a major backlash or even a rejection of globalization; an event that has been feeding fears of deglobalization alongside the results of the US presidential elections and subsequent US policy changes. In the first instance, the increasing deglobalization pressures will most likely reinforce the importance of local ‘players’ (manufacturers and distributors alike) in their home markets but potentially ‘dampen’ their plans for international expansion. Further research is needed as the event unfolds itself.

4 Conclusion

Brexit, more a phenomenon than a singular event, has the capacity to affect the routes to the UK chemicals market. Continuous uncertainty and increased volatility could potentially cause a shift in the supply chain towards official and appointed chemical distributors rather than direct business, non-exclusive distributors and agents. This could be due to the fact that chemical distribution is seen by manufacturers as a way to reduce uncertainty and mitigate risks while they concentrate on their core competences, for instance manufacturing, research and development, logistics ( see table 1 summarizing the conclusions).

Conversely, chemical distributors in the UK mainly comprise of large enterprises and multinationals (LMNEs) with 75% market share and small businesses (SMEs) holding the remaining 25%. However, the inherent characteristics of the latter (e.g. flexibility, adaptability and closeness to customers) appear to provide them with an advantage not only under the current market conditions (e.g. high fragmentation, product specialization, reduction of manufacturing base and price sensitivity), but especially under the emerging landscape caused by the Brexit.

References

Angermann M&A International (2015): Chemical Distribution – Industry and M&A Outlook, available at http://www.angermann-ma.de/fileadmin/redaktion/downloads/publikationen_und_broschueren/Chemiereport_2015.pdf, accessed 2 March 2017.

BCG – Boston Consulting Group (2010): Opportunities in Chemical Distribution, available at https://www.bcg.com/documents/file37956.pdf, accessed 2 March 2017.

Chemagility (2008): United Kingdom Chemical Distribution Report 2008, Chemagility, Surrey.

Chemagility (2015): United Kingdom Chemical Distribution Report 2015, Chemagility, Surrey.

Chemistry Growth Strategy Group (2014): Strategy for Delivering Chemistry-Fuelled Growth of the UK Economy, Department for Business innovation and Skills, available at http://www.chemicalsnorthwest.org.uk/downloads/news/growth_strategy_final.pdf/ , accessed 3 March 2017.

European Union (2003): Commission Recommendation of 6 May 2003 Concerning the Definition of Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, The Official Journal, 124 (1), pp. 36-41.

Grand View Research (2013): Chemical Distribution Market Analysis, Market Size, Application Analysis, Regional Outlook, Competitive Strategies and Forecasts, 2014 to 2020, available at: http://www.grandviewresearch.com/industryanalysis/chemical-distribution-market, accessed 3 March 2017.

Health and Safety Executive (HSE) (2014): Chemical Sector Strategy 2012-2015, available at http://www.hse.gov.uk/aboutus/strategiesandplans/sector-strategies/chemicals.htm, accessed 20 March 2014.

IMAP (2015): A View on the Chemical and Chemical Distribution Market, available at http://dbens.nl/wp-content/uploads/A-View-onthe-Chemical-and-Chemical-Distribution-Market.pdf, accessed 2 March 2017.

Lampadarios, E. (2016a): Success factors for SMEs in the European chemical distribution industry, Journal of Research in Business, Economics and Management, 6 (3), pp. 941-952.

Lampadarios, E. (2016b): Critical success factors for SMEs: an empirical study in the UK chemical distribution industry, International Journal of Business and Management, 11 (7), pp. 67-82.

Lampadarios, E. (2016c): What future for SME distributors?, Speciality Chemicals magazine, March, pp. 36-38.

Lampadarios, E. (2016d): Brexit’s effect on the surfactant supply chain: a distributor’s perspective, 5th ICIS European Surfactants conference, 15th-16th September, Berlin, Germany.